The PTRS-41 anti-tank rifle in 14.5×114 mm caliber

In the eternal duel between sword and shield, the appearance of the tank during WWI called for an adequate response to this new actor on the battlefield. And the answers were not long to come: among them, in 1918, the Germans lined up the legendary “Mauser M1918 TankGewehr” (also known as “T-Gewehr”) caliber 13.2×92 mm SR “Tank und Flieger” (TuF), the first anti-tank rifle (Pic.02). If this is not surprising at the end of WWI, the appearance of an anti-tank rifle among the Soviets at the beginning of the “Great Patriotic War” raises more questions.

Anti-tank rifles for WWII?

Let’s not be so quick as to forget that the majority of tanks used during WWII were far from the armor level offered by the iconic Tiger and Tiger II tanks. At the beginning of the conflict, many tanks were actually “light and medium” and therefore accessible to armaments of “reasonable” power (everything being relative…). As an indication, on the German side, the following figures (from Wikipedia as of April 3rd, 2023) give an overview:

- Panzerkampfwagen III known as “Panzer III”, a 24-ton medium tank: 5,774 units produced from 1935.

- Sturmgeschütz III known as “Stug III”, 23.9-ton assault gun (using the Panzer III chassis): 10,086 units produced from 1940. It seems to be the tank the Germans produced the most during WWII.

- Panzerkampfwagen IV known as “Panzer IV”, 25-ton medium tank: 8,853 units (battle tank only) produced from 1936.

- Panzerkampfwagen VI known as “Tiger”, 57-ton heavy tank: 1,295 units produced from 1942.

- Panzerkampfwagen Tiger Ausf. B, known as “Tiger II”, 68.5-ton heavy tank: 492 units produced from 1944.

Also, the rise of heavy tanks would not overshadow the production in quantity of lighter tanks, like the tank destroyer “leichter Panzerjäger 38(t)“, also known as “Hetzer”, a tank used by the Germans designed on the basis of the Czech tank “ČKD LT vz. 38” in 1943 and produced from 1944… to nearly 2,827 copies (Pic. 03)!

Finally, it is necessary to keep in mind that tanks are not the only vehicles on the battlefield: just for the half-track, the Germans would produce between 1938 and 1945 9,000 “SonderKraftFahrZeug 11″ (Sd.Kfz.11) and 15,252 Sd.Kfz.251 between 1939 and 1945 (Pic. 04). Essential vehicles for the military operation and which would entirely be at the mercy of anti-tank rifles…

To finish putting things in context, at the start of Operation Barbarossa, on June 22nd, 1941, the Tiger tanks were only in the design offices, and the Tiger II probably not even an idea! For the Soviets, the threat was therefore mainly light and medium tanks or even lighter vehicles. So, in the end, these vehicles of less than 25 tons (the weight giving a good idea of the armor level) remained accessible to a “small caliber” (in the French military sense of the term, less than 20 mm) over vitaminized. And the Soviets would not be the only ones to make this observation: the British with the Boys in .55 Boys caliber, but also the Polish with the Wz.35 Maroszek and its surprising e ammunition of 7.92×107 DS and the Germans with their PanzerBüchse 39 (PzB. 39) in 7.92×94 (just as surprising as the Polish ammunition) … not to mention the Finns and their superb Lathi L-39 in 20×138 mm B (Pics.05 and 06). As an indication, according to the Soviet General Staff, on June 1st, 1941, the German army disposed of 25,298 anti-tank rifles! According to Wikipedia (March 3rd, 2023), the PzB.39 would have been produced between 1939 and 1941 to 39,232 copies!

But as always, before producing a weapon, you have to determine both caliber and ammunition.

The 14.5×114 mm

Soviet thinking about anti-tank rifles obviously does not date from the German attack. In the 30s, the subject was studied, especially with the caliber 12.7×108 mm, whose ammunition offers performances finally close to the 12.7×99 mm (Pic. 07). However, these two calibers, excellent for the engagement of light vehicles, light fortification or for low-altitude air defense, were already reaching their limit on armored vehicles and especially on battle tanks. The thing is not really surprising, their ammunitions are globally designed by feedback from experiences made during WWI. This deficiency was noted by the Soviets after multiple tests with this caliber. Testing of anti-tank rifles using 12.7×108 ammunition was definitively stopped in 1942.

Thus, after reconsideration of the ins and outs of the needs, it was estimated that a 14.5 mm bullet of about 64 g propelled at 1000 m/s could penetrate, at 500 m, 20 mm of armored steel under an incidence of 60 ° (the 500 m not being the alpha and omega of the use of this caliber … of course!).

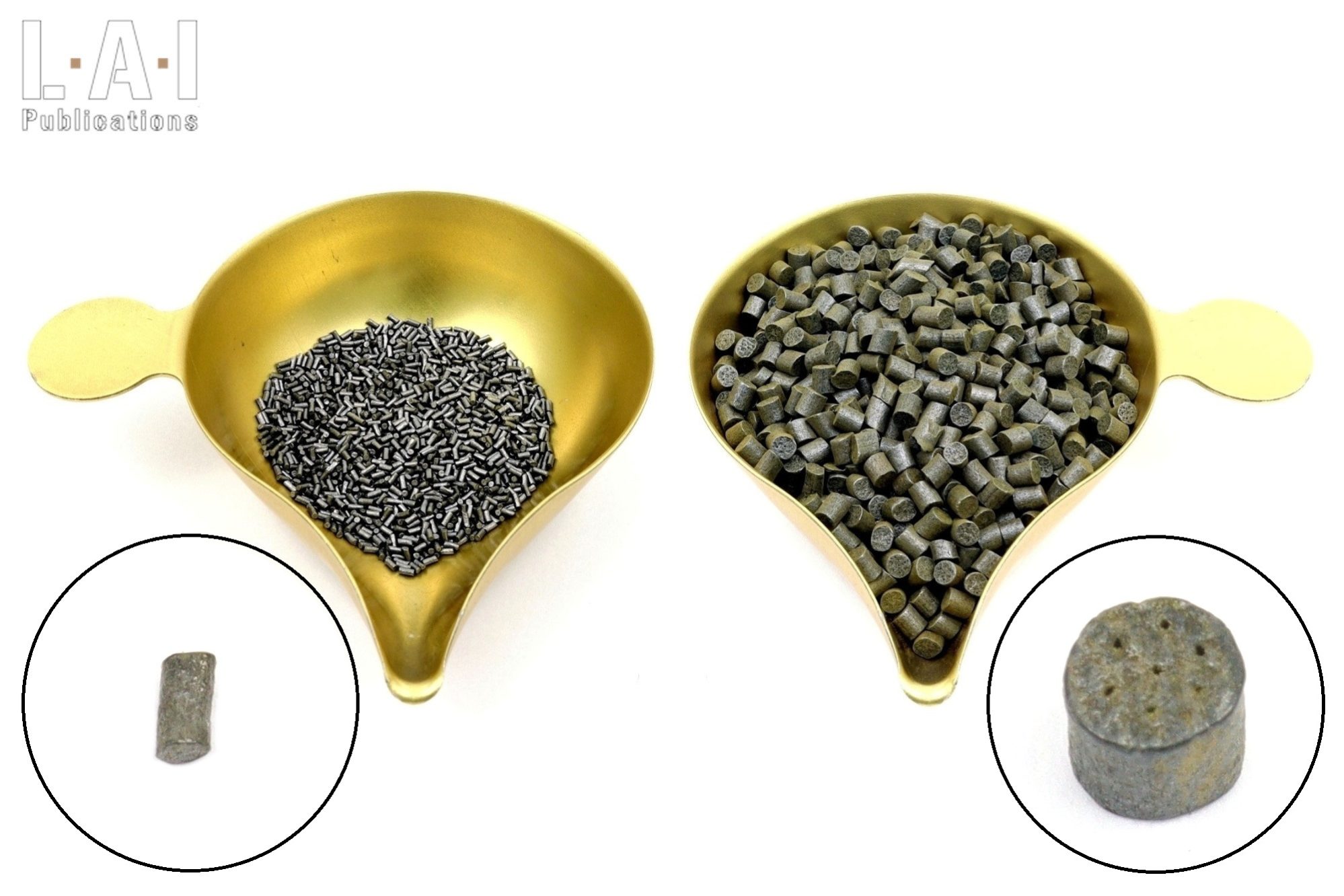

As a result, an ammunition was designed and perfected between 1938 and 1940 and on July 16th, 1941, the “14.5 cartridge with B-32 bullet” was officially adopted. It is therefore a 14.5 mm bullet mounted on a 114 mm case, which is announced in its armor-piercing-incendiary (API) variant B-32 at 1010 m/s in the barrels of the PTRD-41 (1227 mm) and PTRS-41 (1216 mm) (Pic.08). This ammunition, designated 57-BZ-561S in the Soviet military nomenclature, propels a bullet announced at 64 g using no less than 30.08 g of tubular single base heptaperforated nitrocellulose (7 holes – Pic.09). At 1010 m/s (V0), the bullet develops 32,643 joules: a little less than twice the 17,030 joules of a 12.7×99 MEN M33 of 43 g fired at 890 m/s in the barrel of an M2! But let’s compare what is comparable… However, in the West, although there were trials of .60 caliber in the United States, no caliber was ever adopted. The 14.5×114 mm B-32 bullet is composed of a hardened steel core coated in lead, topped with an incendiary composition while contained in a tombac or galvanized plated steel jacket. The incendiary composition is a classic in the USSR: mixture of barium, aluminum and magnesium powder, very stable, which is naturally initiated by the energy of the impact. The color code of the ammunition is, in the USSR, a black over red tip. In terms of design, this ammunition is simply the “adapting” in 14.5×114 mm of the B-32 of 12.7×99 mm. … Except that in the 14.5 mm, the core of the bullet has almost the dimensions of the 12.7 mm bullet! The 14.5×114 mm B-32 is, even today, the standard ammunition for this caliber: there is no service ammunition with “ordinary” bullet consisting only of jacketed lead, or even mild-steel core. The thing is logical, it is an anti-materiel and not aa anti-personnel ammunition… at least from a technical point of view. Of course, as generally on equipment produced over such a long period, there are production variations and especially in this case, in the bullet length.

In the search for improved piercing capabilities, a tungsten carbide core API ammunition would be adopted on August 15th, 1941 (about a month after the B-32): it is the BS-41. Tungsten carbide is significantly denser than steel (almost twice as much!), for a close mass (announced at 65 g), the bullet is shorter than the B-32. Otherwise, it takes over the incendiary characteristics of the B-32. It should be noted here that this ammunition is generally presented as “the first 14.5×114 mm ammunition” used during WWII. However, Russian author David Naumovich Bolotin details with precision the development of this caliber and these ammunition and gives dates without appeal. Moreover, the thing seems logical: in an emergency, it was easier to extrapolate a technology already known and mastered than to venture from start to finish on unknown and more expensive ground. The BS-41 would survive only a short time after the Great Patriotic War: its use seemed to be devoted to the anti-tank rifle, which would also be stored in the arsenals at the end of the war. If the BS-41 is actually described in the early manual (1957) of the KPVT machine gun, it is specified there that the adoption of the BST, an ammunition with the piercing-incendiary-tracer bullet, also with a tungsten carbide core, was intended to replace it. The BS-41 is no longer described in the KPVT manual of 1984.

In absolute terms, tungsten carbide is significantly superior to hardened steel in the piercing purpose: both harder and denser, the performance of this ammunition was probably superior to the B-32… but at a superior cost. As an indication, modern variants of 14.5×114 mm tungsten carbide core ammunition are advertised by its manufacturer as having twice the piercing capabilities as a B-32! The BS-41 is also written as “more powerful” and “only intended to be fired on tanks” by the service manual. The color code of this ammunition was: a fully varnished red bullet (even overflowing on the case’s mouth) whose point and primer were black varnished.

The Russians also tried a stranger concept (although already experimented with by others): the armor-piercing tear gas ammunition called BZKI. This experimental ammunition was developed during the war but did not have a future due to its very limited effectiveness. Heavily inspired by German’s “Patrone 318 SmKH-Rs-L’spur” and “Patrone 318 SmK-Rs-L’spur “, the goal is to force the evacuation of a tank by saturation of tear gas inside its hull…

Of course, other ammunitions would be produced after the war: piercing-incendiary-tracer (BZT and BZTM), tracer-incendiary (ZP), “instantaneous incendiary” (MDZ – often presented as explosive-incendiary) … But we are not going to dwell here on the study of the 14.5×114 mm ammunition, and in particular of its modern variants: the book of Philippe Regenstreif is full of technical information for those who are interested… Let’s not indulge in shameless plagiarism here… We also learn that the Soviets experimented with another even more powerful anti-tank ammunition as well: the 14.5×148 mm B… or a 14.5 mm bullet mounted on a 23×152 mm B socket! This ammunition was intended to be fired into a rifle developed by Mikhail Nikolayevich Blyum in 1943.

Like the 12.7×99 mm and 12.7×108 mm, the 14.5×114 mm caliber would see its use survive WWII, being used in particular in the KPV machine gun from 1954… but also in the PTRD-41 and PTRS-41 today still!

Once the caliber and ammunition had been chosen, it was therefore necessary to give birth to one or more rifles.

A birth in pain

Preliminary precaution: we obviously do not have first-hand access to the history of the adoption of anti-tank rifles in the Soviet Union. Thus, the historical part that you will find below comes in very large part (but not only and without copying and pasting!) from the excellent book of D.N. Bolotin “Soviet small-arms and ammunition“, whose chapter about anti-tank rifles is very comprehensive. Let us render unto Caesar, which is Caesar’s.

The study of anti-tank rifles began early in the interwar period and in 1931, Leonid Vasilyevich Kurchevsky, designed a 37 mm recoilless rifle tested from July 1932. Even if it did not lack interest, this weapon would not be produced in large quantities (and probably only for the purpose of troops trial). This work would rather close the door to the development of a portable anti-tank weapon of medium caliber (in the French military sense, between 20 and 40 mm).

On March 13th, 1936, the Soviet authority passed a special resolution regarding the development of anti-tank rifles in 12.7×108 mm caliber. The design was entrusted to designer Mikhail Nikolayevich Blyum (the same person who would later make the rifle in 14.5×148 mm B), Semen Vasilyevich Vladimirov (the future designer of the KPV machine gun) and Sergey Aleksandrovich Korovin (the designer of the TK-26 pistol) who designed 15 rifle models between 1936 and 1938. However, none met expectations… and in the same way as L.V. Kurchevskiy’s rifle closed the door to medium caliber, these studies closed the door to 12.7×108 mm.

From 1939, rifles for the 14.5×114 mm were requested from Nikolaï Vasilyevitch Rukavishnikov, S.V. Vladimirov, and Boris Gavrilovich Shpitalniy. N.V. Rukavishnikov’s rifle, a 5-shot semi-automatic was gas operated. B.G. Shpitalniy’s rifle was single-shot, with automatic opening of the breech during firing, the implementation being ensured by a short recoil of the barrel. S.V. Vladimirov’s rifle worked by long recoil of the barrel and had the particularity of being disassembled into two sub-assemblies easily transportable by a pair of soldiers (because, yes, the anti-tank rifle remains a crew-served weaponA weapon which is designed to be used by a team of several p... More). It is noted that on all these weapons, the opening of the closing mechanism is automatic when firing, even for manual or 1-shot repeating weapons. The thing is actually made necessary by the considerable effort that is to be made to extract the case of the chamber at the end of the shot. Most of the 12.7×99 mm bolt-action rifle shooters experienced that… But to a lesser extent: we must keep in mind here that the ammunition develops nearly twice the kinetic energy of a 12.7×99 mm. From August 13th to 31st the tests concluded that N.V. Rukavishnikov’s rifle was the best fit. The weapon was practical, easily transportable by two men and allowed a practical rate of fire of 15 rounds per minute while piercing 20 mm of steel under an incidence of 70° at 500 m. Further development of this weapon was initially approved for further testing on October 7th, 1939, under the command “ПротивоТанковое Ружьё обр. 1939” (“ProtivoTankovoe Ruzhe obr. 1939“, or “1939 anti-tank rifle”). However, the concept being finally thought by the Soviets as inefficient against modern battle tanks and faced with certain problem encountered, the work would finally be slowed down (without being stopped). On August 26th, 1940, the anti-tank rifles produced were even withdrawn from service. We note here that the Soviet author D.N. Bolotin considers that the development of the anti-tank rifle in the USSR would experience the same disappointments (with problems of analysis on the tactical contribution of this type of weapon) as the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More (mentioned in our article on the PPSh-41). We can only agree. In June 1941, reconsidering things in the face of the German attack, N.V. Rukavishnikov’s rifle was finally approved hastily without all his defects being corrected. If the effectiveness of the weapon was considered by the Soviets to be superior to foreign equipment because of its caliber, N.V. Rukavishnikov’s rifle was ultimately too complex for military use. It can be noted that in parallel with his work on the semi-automatic rifle, N.V. Rukavishnikov would develop lighter and more economical manual repeating models… an approach that would be found with Degtyarev’s weapon. The Soviets even tried to copy the concept of the German PzB.39 in caliber 7.92 x 94 mm, but without conclusive results (the caliber seems to be the 7,62×92 mm).

In July 1941, probably on the direct orders of Stalin, who insisted on the importance of anti-tank rifles in the face of the German advance, new designers were appointed to this task: they were the now famous Vasily Alekseyevich Degtyaryov (DP, DShK-38, RPD-44) and Sergey Gavrilovich Simonov (AVS-36, SKS-45) who were appointed to get back to work in haste. Working “night and day”, the two designers offered weapons in less than 22 days! Probably one of the fastest examples of development there is… when necessity is law!

At the end of July, S.G. Simonov came up with two models of removable magazine-fed rifles. The first, developed in collaboration with Georgiy Semenovich Garanin, Sergey Mikhaylovitch Krekin and Aleksandr Andreyevitch Dementyev, automatically opened the breech when firing and ejected the spent case, using the principle of barrel recoil. The second, designed by V.A. Degtyarev alone, only opens the rotating breech when firing, without ejecting the spent case. Both weapons were fed by a 5-round magazine. At the beginning of August of the same year, both weapons are tried: the second model is preferred, the weapon being simpler. However, neither of the two weapons was satisfactory from an operational point of view and the designer was sent back to his workshop (probably benevolently… but in a hurry: Stalin awaits!) With the instruction, in a spirit of simplification, to convert his weapon into a single-shot rifle. It is noted in particular that the two weapons required the ammunition to be lubricated to properly extract … Because yes, contrary to a legend (half well founded), the lubrication of ammunition is sometimes desirable for the correct functioning of weapons … As mentioned above, the extraction of these calibers can be problematic. Having made the requested changes, V.A. Degtyarev would soon return (Stalin awaits…) with a new prototype that would become the PTRD-41 (Pics.10 and 11). The weapon presented has the advantage of being extremely simple to produce, mainly from lathing operations… But that’s another story.

For his part, S.G. Simonov, to save time, relied on his previous work and in particular on his 1938’s prototype semi-automatic rifle (unfortunate competitor against the SVT-38 of F.V. Tokarev). Replacing the magazine by an En Bloc clipDevice containing ammunition and intended to be completely i... More (clearly heavily inspired by the Garand!) with, according to D.N. Bolotin, “the goal of lightening a weapon” already heavy, he would also redesign the trigger mechanism, with the curious particularity of having an articulated trigger … its lower part! The weapon thus obtained is simpler (from any point of view, including production) and more reliable than N.V. Rukavishnikov’s weapon. During the tests, on more than 1000 cartridges fired (in 14.5 mm, it is quite a number …), no jamming for the PTRS-41 and 2 for N.V. Rukavishnikov’s weapon.

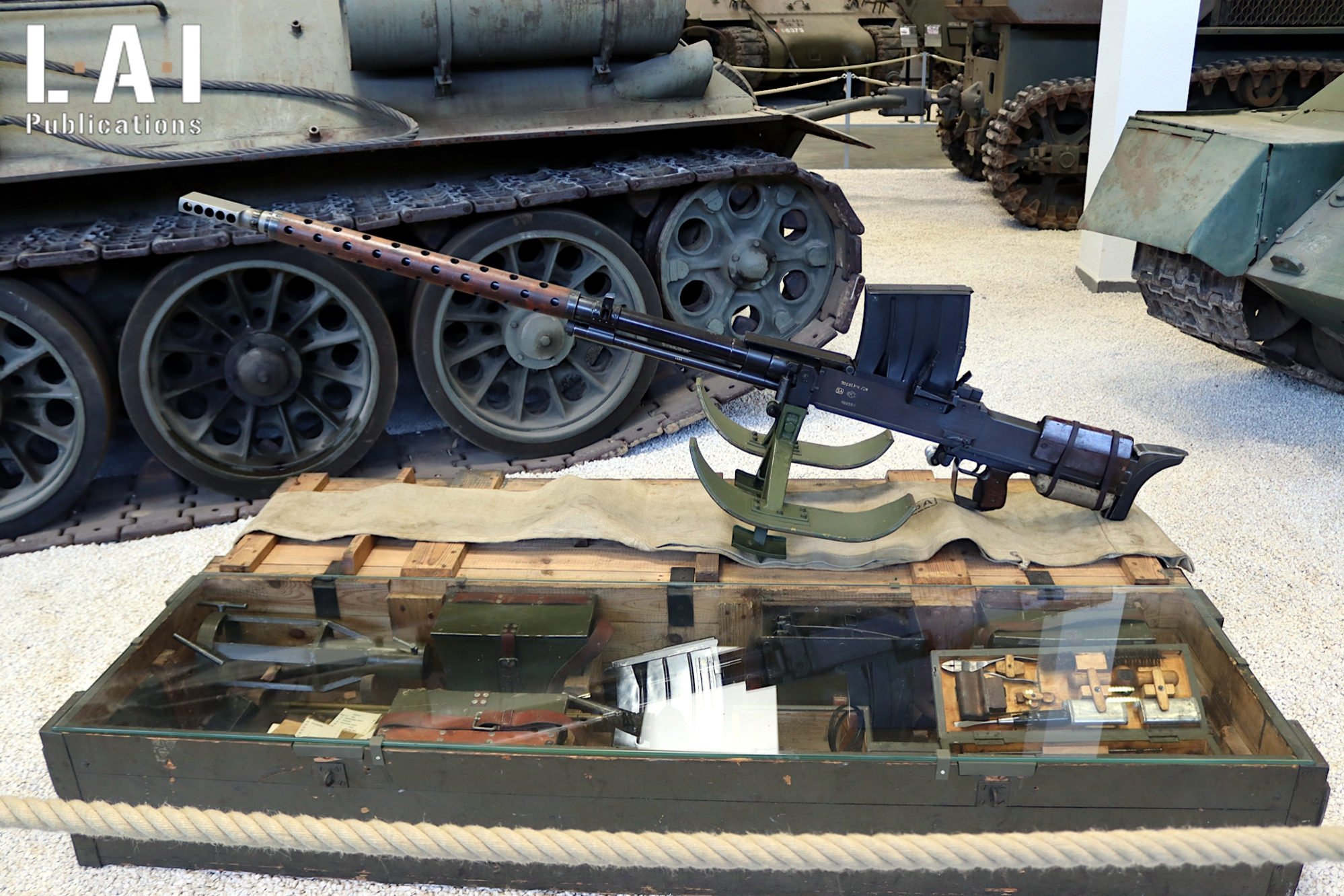

At the end of the firing tests of August 29th, 1941, the weapons of V.A. Degtyarev and S.G. Simonov are adopted on the respective names: “ПротивоТанковое Ружьё системы Дегтярёва образца 1941 года” (ProtivojTankovoe Ruzhe systemy Degtyareva obr. 1941 – PTRD-41) and ” ПротивоТанковое Ружьё системы Симонова образца 1941 года” (ProtivoTankovoe Ruzhe Simonova systemy obr. 1941 – PTRS-41). Both weapons were immediately put into production, the simplicity of V.A. Degtyarev’s weapon allowing a faster commissioning of the weapon: this was its primary purpose. D.N. Bolotin reports that it could be produced at the Kovrov plant 30 to 40 PTRD-41… per hour! Thus, while V.A. Degtyarev’ s weapon came out of the Kovrov factory, the production of S.G. Simonov’s, more complex, was set up in Tula. This production was slowed down due to the advance of German troops and the necessary move of the factory to Saratov. The two weapons remain mechanically very simple: we are very far from the “hyper-technological” concepts of “Wunderwaffen ” of Nazi Germany… Think Different?

In the autumn of 1941, the first PTRD-41s demonstrated their effectiveness on the front, at engagement distances of up to 400 m. At 100 m, the weapon would even have been able to penetrate the turret of many medium tanks: at such a distance several sources announce that the B-32 (with a V0 of 1010 m/s) can pierce 40 mm of armored steel. The PTRD-41 having had an important role in the defense of Moscow, V.A. Degtyarev and several members of his team won the medal “For the Defense of Moscow”. S.G. Simonov would also be the recipient of this medal although his weapon participated to a lesser extent in this battle. It is, among other things, the Battle of Stalingrad which was to the PTRS-41 what the Battle of Moscow was to the PTRD-41: a feat of arms that would be symbolized in particular by the fighting around the “Pavlov House”, named for the celebration of the non-commissioned officer Yakov Fedotovich Pavlov.

If the behavior of the weapons was suitable during the winter, the arrival of spring and mud (the famous “rasputitsa”) was less favorable, and modifications were necessary to make the newly produced weapons more reliable. In the same spirit a “memo” in 5 points (“Пять советов бронебойщикам” – Pyat sovetov broneboyshchikam – 5 tips for armor piercers!), written by V.A. Degtyarev for its rifle, was sent by the army to the operators of anti-tank rifles:

- The anti-tank rifle is most effective at distances not exceeding 250 – 300 m.

- The rifle is reliable if it is properly maintained, and its moving parts lubricated (nothing new in reality!)

- Good maintenance of the barrel allows it to maintain its penetration performance after 500 rounds despite a slight loss of muzzle velocity.

- The feeling of recoil is greatly attenuated by the sliding of the receiver into the stock provided that its slide is properly lubricated and clean. Its cleaning is easy, by some pressures on the stock.

- The weapon is accurate but requires a good adjustment of the sights and a good use of the cheek-piece and the bipod (in short, a good firing position!)

In reality, this is common sense… but which is too often lacking! Even today, we meet people who explain to you that you should not put oil in weapons or that 4 drops are enough … I refer those interested to Chapter 13 of my book, available on this same website…

This type of memo is a direct return to a practice in vogue during WWII in the USSR: that of visiting equipment designers at the front and exchanging with soldiers. The majority of Soviet small arms designers would sacrifice to practice. D.N. Bolotin sees a double advantage: that of bringing a better knowledge to their equipment, but also of developing the soldier’s attachment to his armament. Both things are indeed of prime importance: knowledge and attention to the equipment available for combat… which is always the best we can have, since we have no other! But even the most basic things get lost… We shouldn’t spend too much time on training, should we? These are “full-time job equivalents”… I have heard too much of this kind of nonsense from the mouth of French administrators… but fortunately, not everywhere! Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater… But let’s remain critical!

Production soared during the war: in 1941, 17,888 PTRD and 77 PTRS were produced, in 1942, 184,400 PTRD and 63,308 PTRS! In this search for productivity, these weapons benefited from a new rifling method of the barrel developed for the USSR by Mikhail Stepanovich Lazarev and Sergey Ananyevich Chernichkin in Kovrov: button rifling. By putting together all efforts to reduce the production time of the PTRS-41, between 1941 and the fall of 1943, the production time was reduced to 52.6% of the original production time. From 1943, the request of the Red Army was met: each regiment could count on 54 anti-tank rifles. Think different.

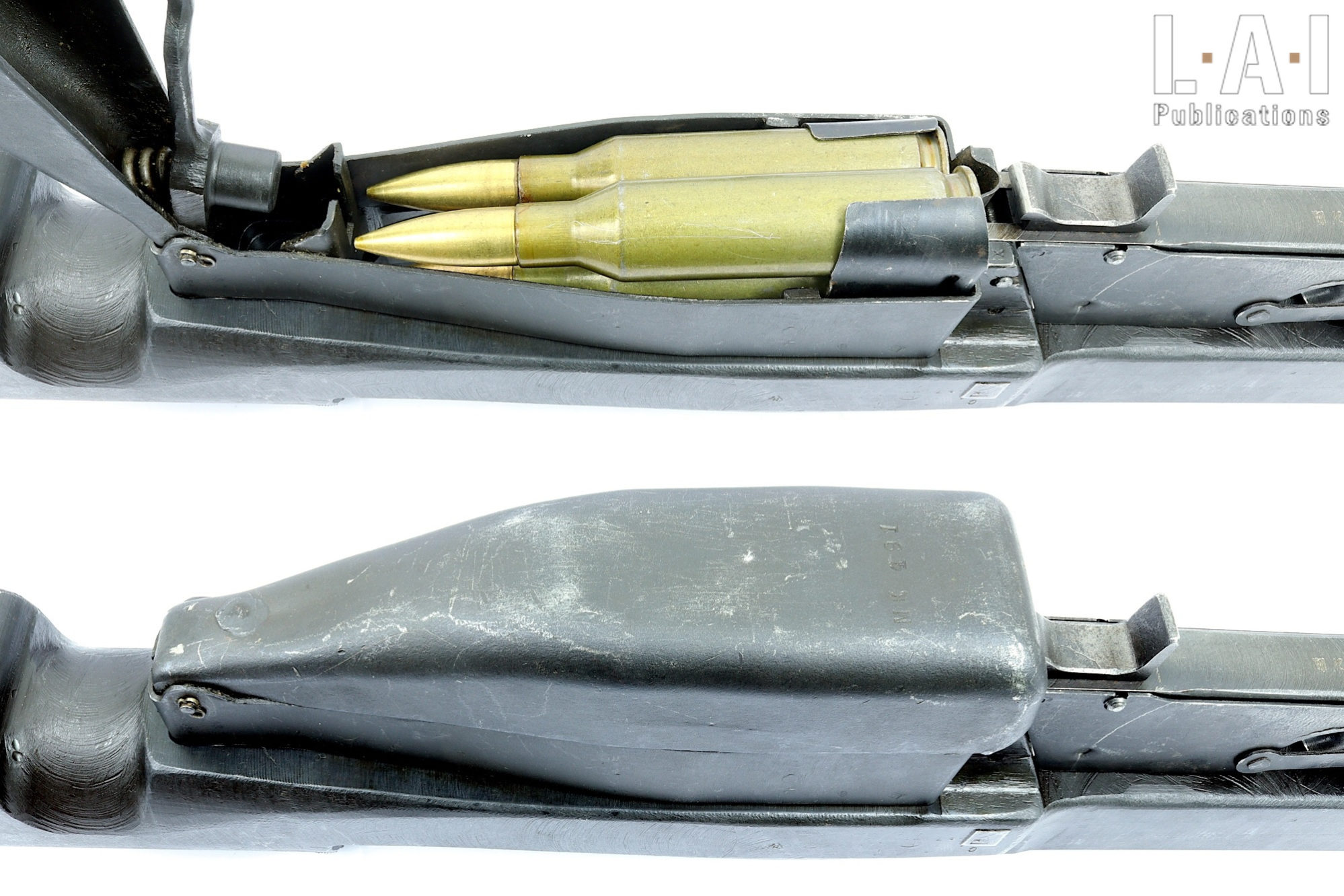

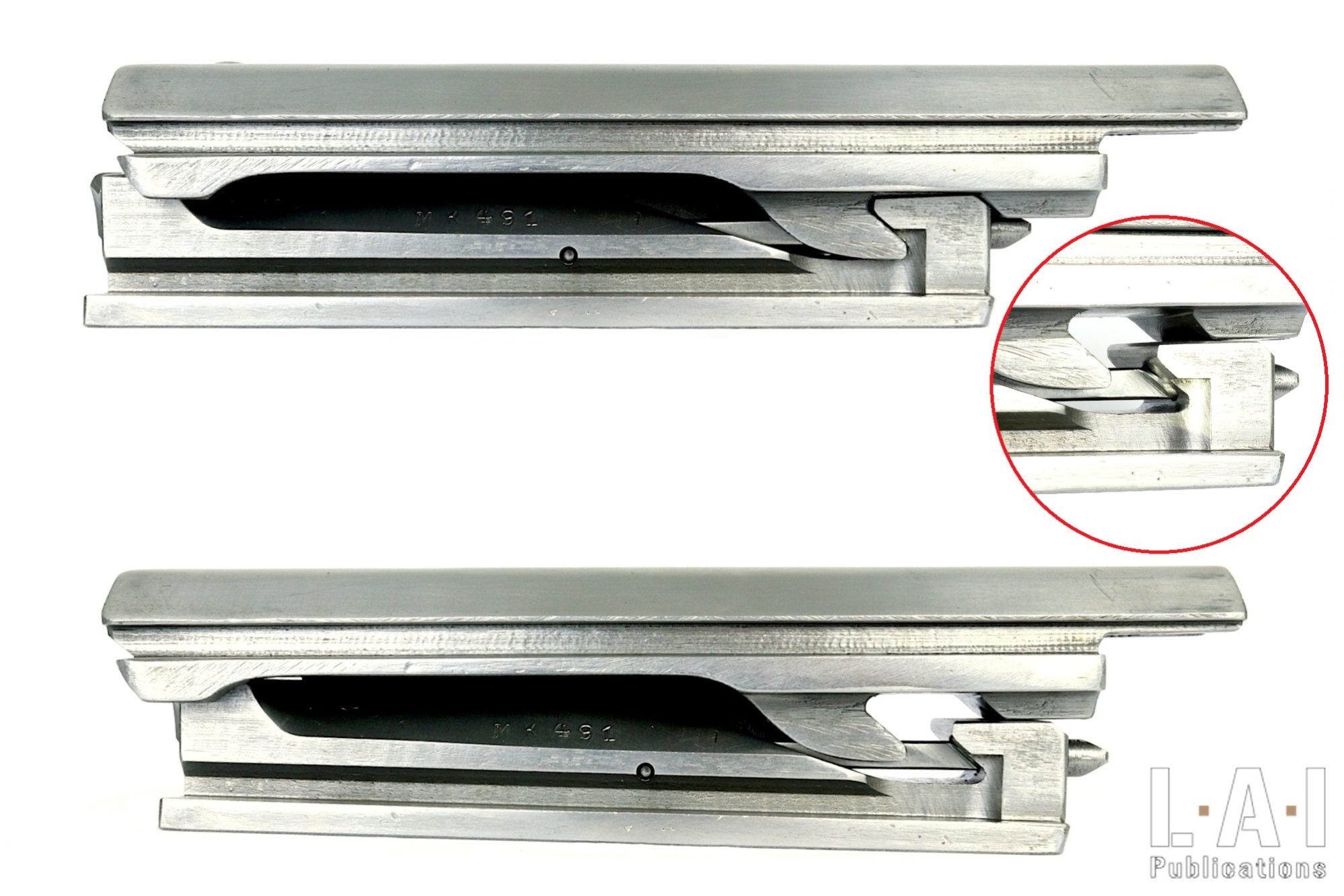

An almost classic implementation

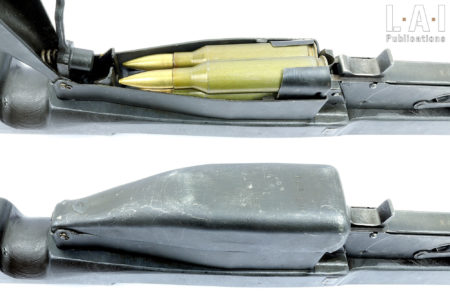

Externally, the controls of the weapon look classic. If we therefore find a cocking handle attached to the breech carrier on the right side, the feeding of the weapon has been somewhat thought outside the box. Indeed, the weapon is (or at least, can be) fed by a 5-round En Bloc clipDevice containing ammunition and intended to be completely i... More that is introduced… by the bottom of the weapon (Pics.12 and 13). It is therefore necessary to open the bottom of the magazine (operation usually reserved on other weapons for unloading!) to position the clip, then close the lid. A large lock is therefore positioned at the back of the magazine hatch for this purpose. The operation is clearly not optimally ergonomic: on the one hand, it is clearly difficult to achieve by the shooter himself (even if the service manual presents the thing), but above all it requires a significant ground clearance or to pivot the rifle to one side (something that the bipod allows). Certainly, with habit, we get used to everything … But clearly, this drawing does not seem to us the best thought out. When there are two people, the thing is less complex, but not optimal… As mentioned above, it is stated by D.N. Bolotin that this system, developed in emergency, had as its primary purpose to lighten the weapon, which is perhaps true if we consider that the team must carry several magazines. In our opinion, it probably also (especially?) has for vocation to simplify and make reliable the weapon at a time when the production of interchangeable magazine was not necessarily obvious on this type of armament. Even on the SVT-40, it’s more of a removable magazine than an interchangeable magazine. Another disturbing element, the clip must be introduced in the right way! Again, this is not optimal, and the user probably pays for the urgency of the development of the weapon. To make a clip without any sense of introduction, it would probably have been necessary to retain an even number for its capacity… so to decrease to 4 or bring up to 6. Unlike the Garand rifle, its clip does not eject on its own when firing is done: it is therefore necessary to remove it by opening the magazine. Fortunately, the using of the clip is not a need: the feeding lips are machined out inside the receiver (Pic.14). One can thus feed the cartridge inside the weapon one by one, as on the majority of repeater…. One even wonders if the thing is not preferable! The magazine lid is thus used for its more classical unloading purpose.

Probably for the sake of safety for the pair, the opening of the magazine is only possible if the Bolt Carrier Group (BCG) is at the back. To do this, the magazine latch is mechanically secured to the position of the breech stop (which also acts as a control for the closing safety as we will see later).

So, to feed, we pull the BCG at the back until it is hung on the breech stopper, then we open the magazine, we insert the clip and we close the magazine taking care that the clip does not come out. No device retains the clip in the weapon: the simple friction of the clip on the receiver ensures in principle this function. Once again, this is not optimal! Once the clip is introduced, the BCG is pulled slightly backwards in order to release the breech stop, then the BCG is allowed to return to the closed position under the action of the return springs assembly. As always, we do not accompany the BCG at the risk of generating an incomplete closure: the effort to take the ammunition out from the magazine is considerable.

The weapon is ready to fire. It has a manual safety on the right side: it is a large lever that can be positioned at the rear (after a movement of about 180 ° – Pic.15). It then hinders the access to the trigger by the right side (so for a right-handed shooter… but the left-handed shooter will also be embarrassed to a lesser extent) while immobilizing the hammer… by hindering the guiding rod of its spring that crosses the hammer’s crest (Pic.16)! Original, but effective.

As already mentioned, what surprises when shooting with this weapon is the movement of the trigger. This one does not slide backwards (as on Colt 1911 or a TT-33), nor rotates downwards (as on most other mechanisms), no it rotates upwards. Its pivot is therefore downwards. This provision was probably adopted to simplify the production of the trigger mechanism. Nothing prohibitive in itself, it is a matter of habit.

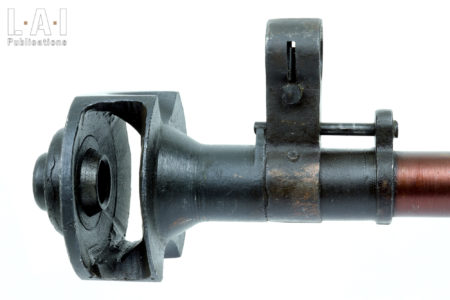

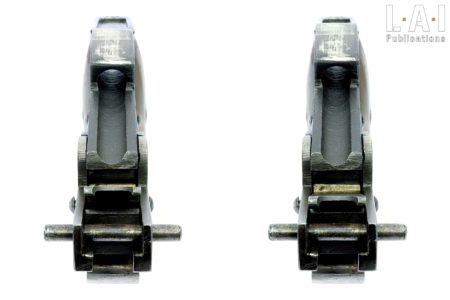

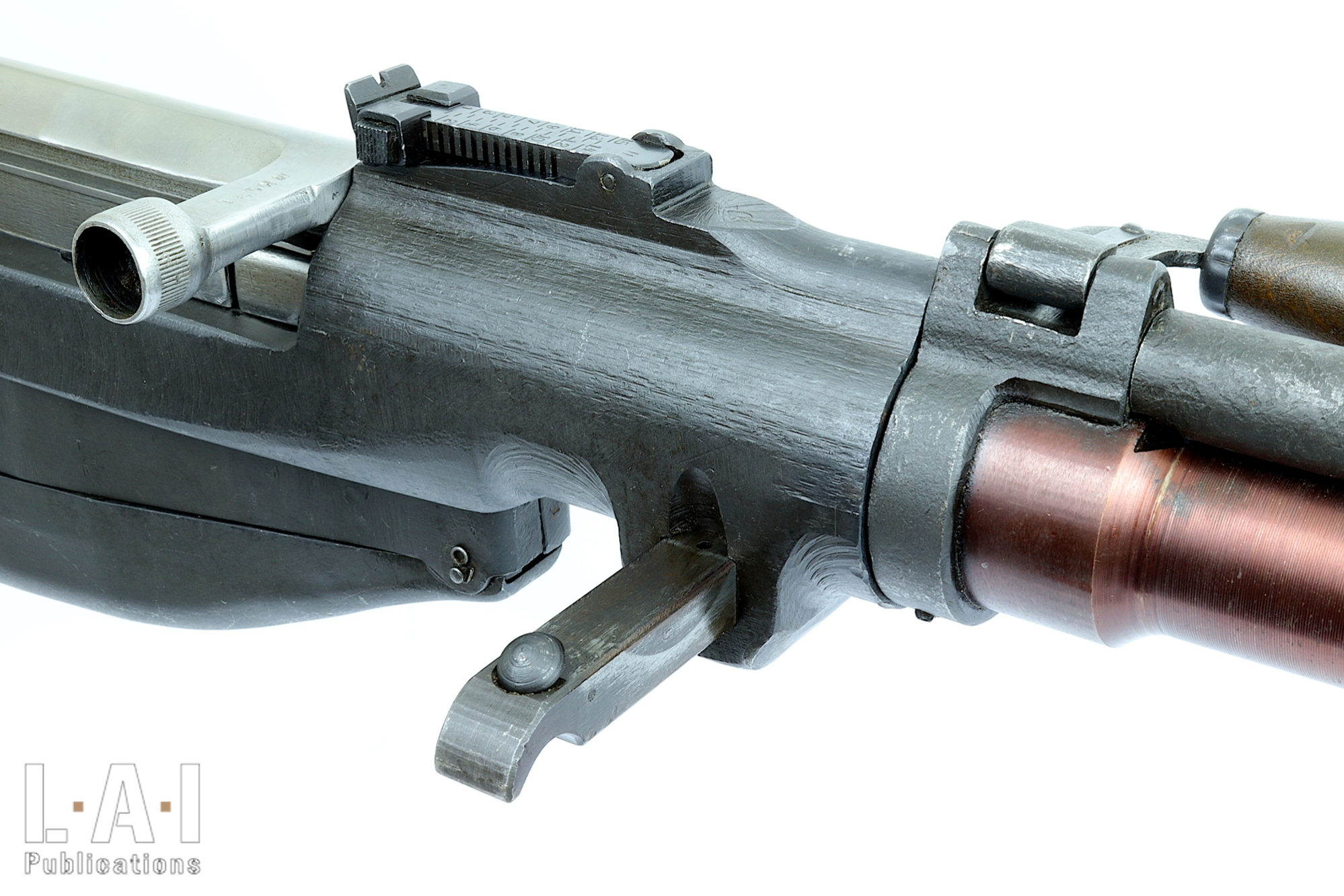

The sights are classic among the Soviets of this time: a U-shape rear sight notch arranged on a leaf, graduated from 400 to 1500 m (Pic.17). The front sight is protected by a hood (Pic.18). It is adjustable in direction, but not in elevation as on some other Soviet weapons: the level of accuracy of this weapon, although excellent in its field as we will discuss in the shooting section, does not require as fine an adjustment as infantry combat requires. The target is broader, even when aiming a specific part of the vehicle.

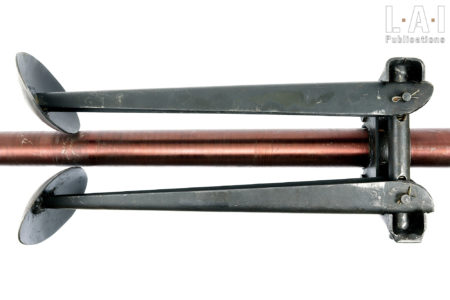

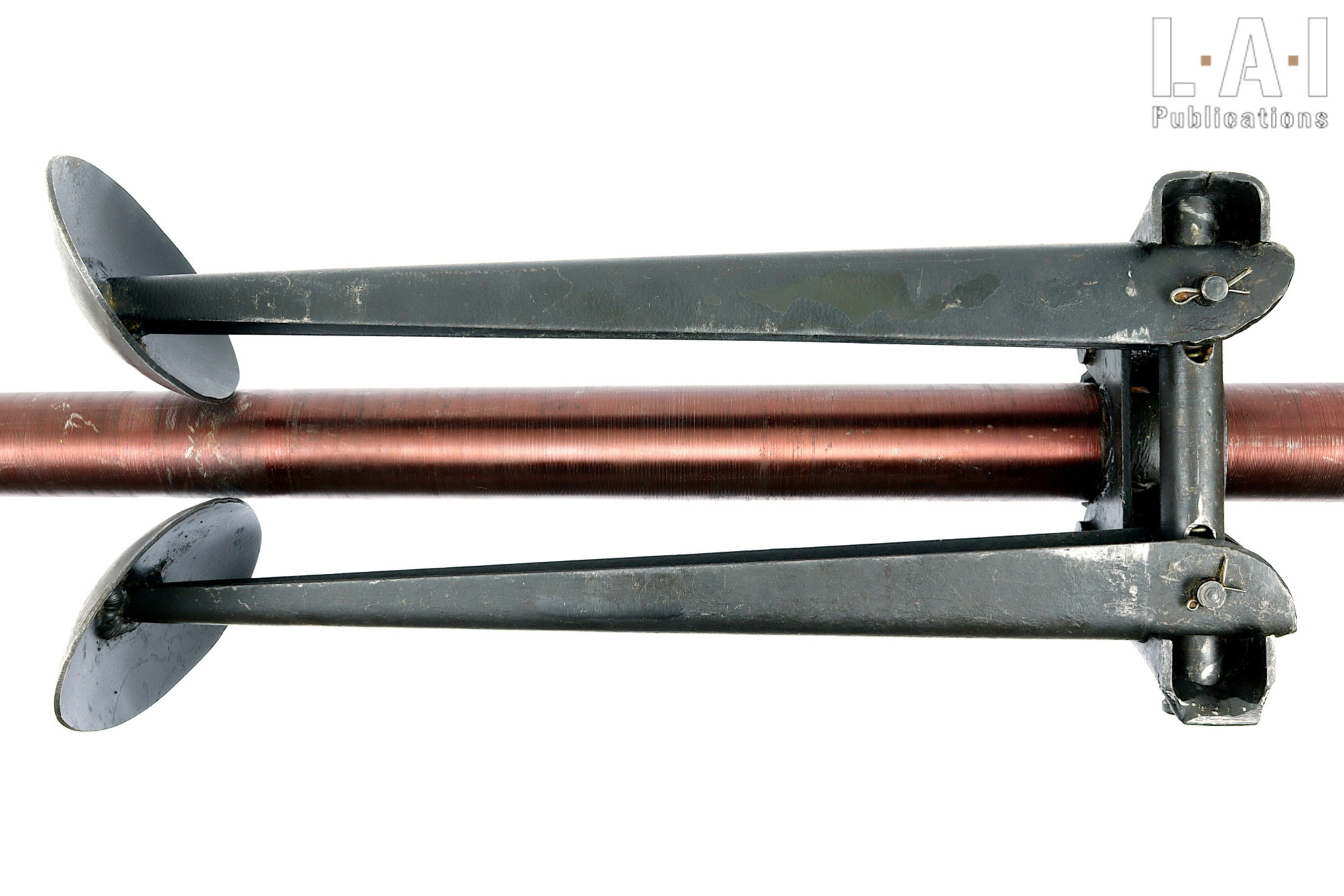

The weapon is mounted on a folding bipod with wide soles, thus compatible with soft floors (mud, snow – Pics.19 and 20). If this bipod is not adjustable, it should be noted, however, that in use, it is much more practical than the infamous bipod of the DP machine gun!

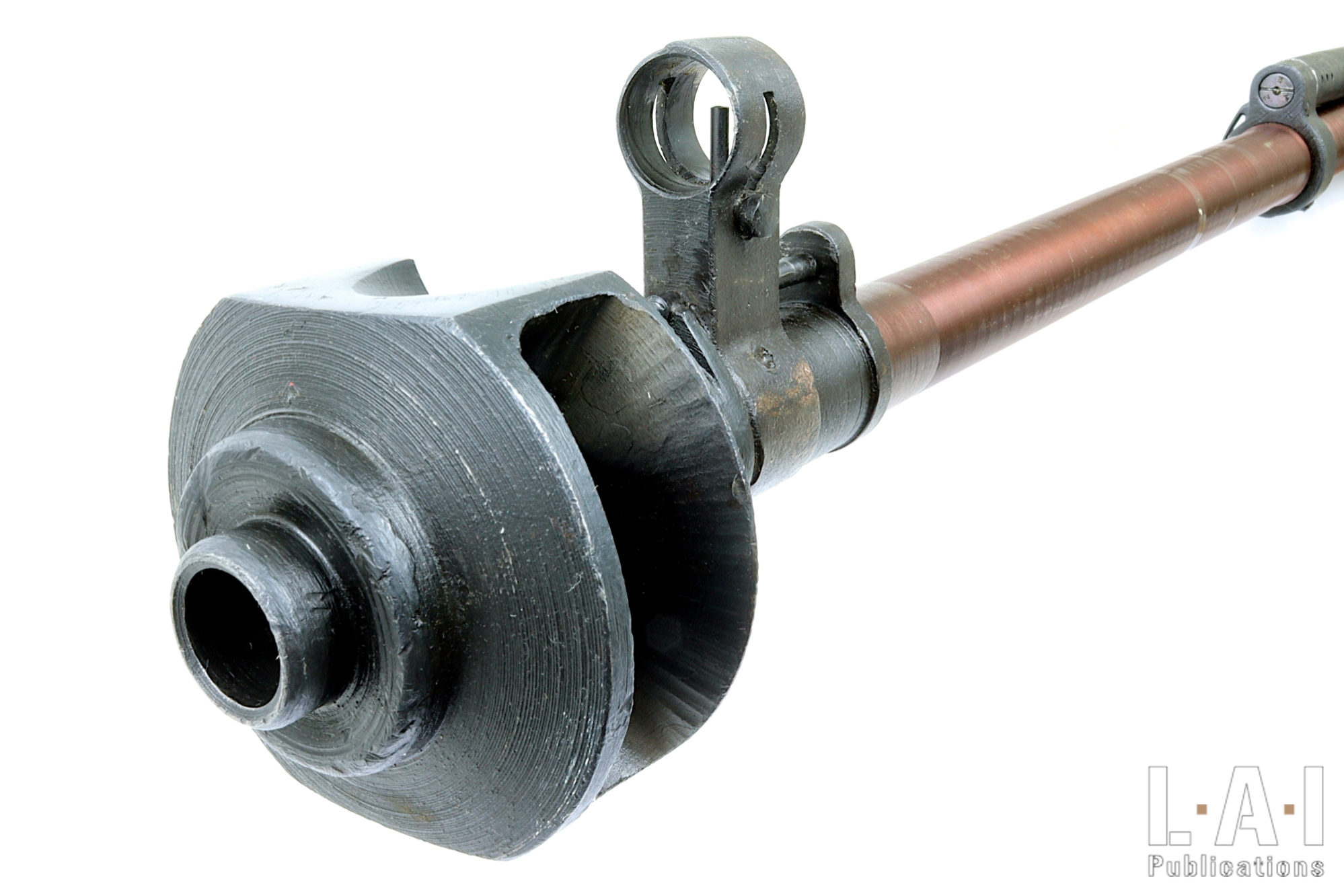

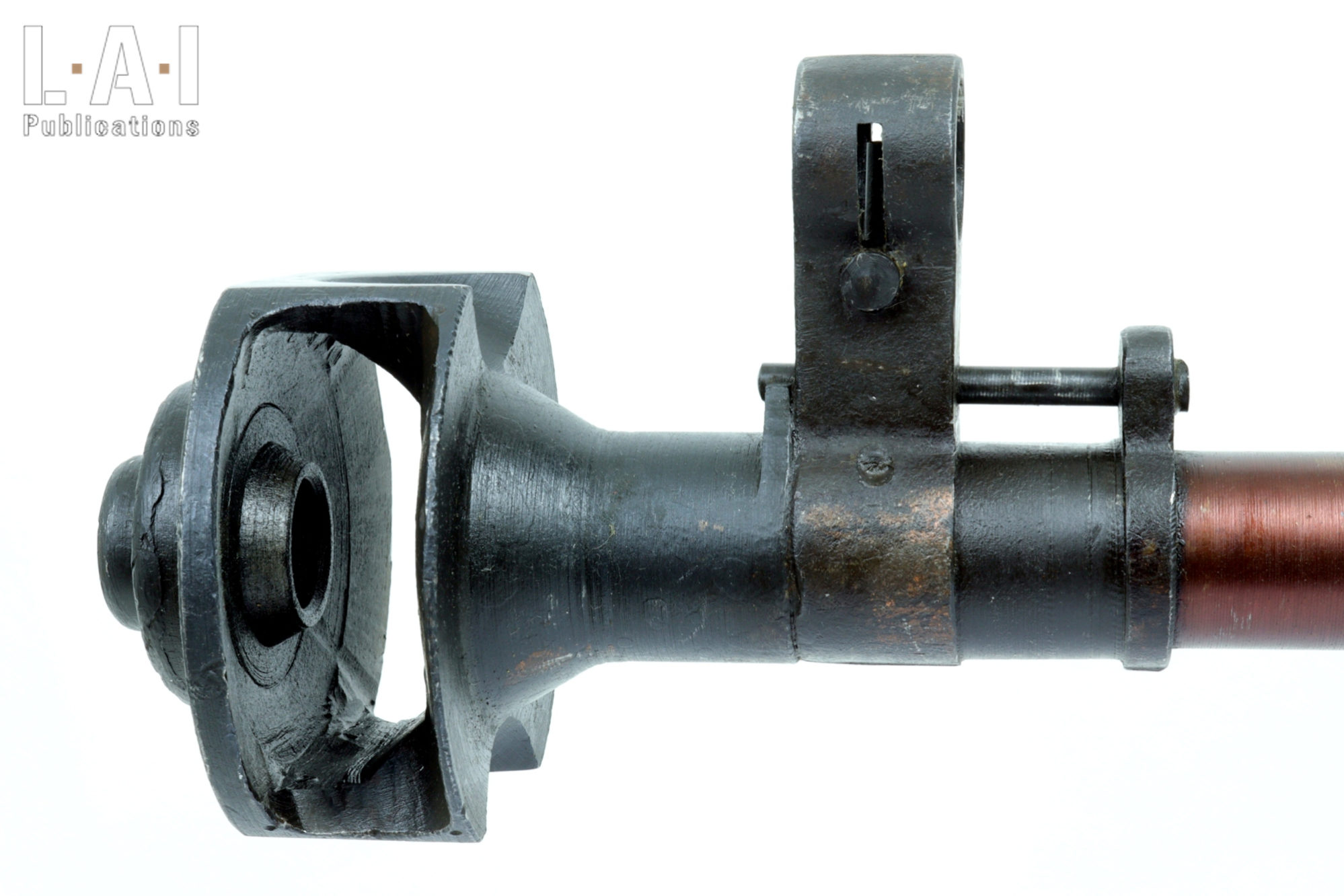

For shooting comfort, the weapon can rely on: its weight (20.93 Kg, quite hefty!), a wonderfully designed muzzle brake (Simonov had already worked the subject since the AVS-36) and a stock with a heavily padded butt plate (Pics.21 to 23). It should be noted that the service manual shows a shoulder pad… that we have never seen personally! The design of the muzzle brake is very neat: effective, it raises only a “little” amount of dust off the ground compared to other weapons and for a weapon of this caliber. In addition, the shooter is quite spared from the blast effect… on the other hand, the weapon does not spare the people next to the shooter (Pic.24). Let’s be clear though, the blast effect does have quite an impact and can be straining for the shooter especially during long shooting sessions. For the observer of a demonstration, the best is to position within the 6 hours of the shooter: it is then very bearable.

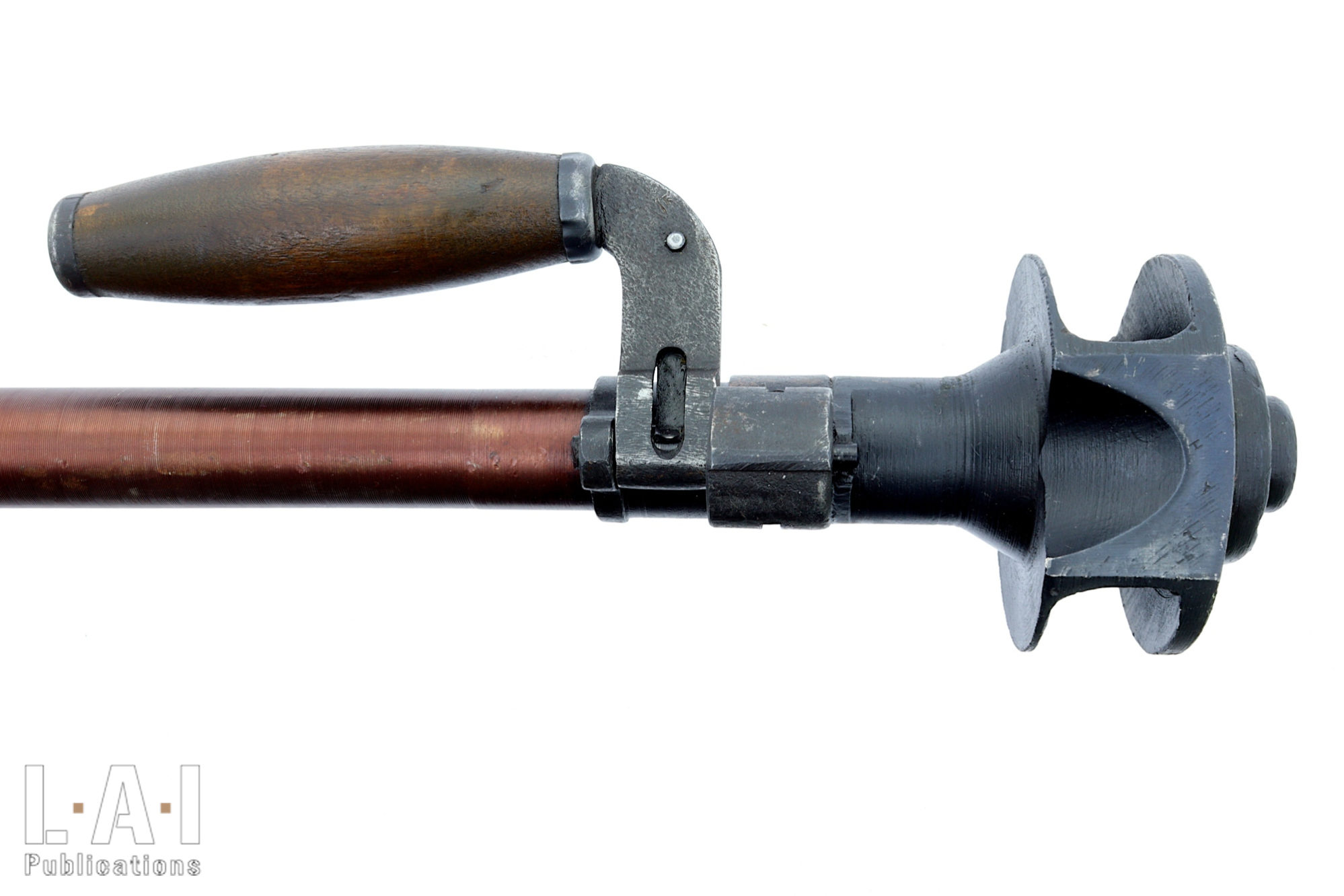

For transport, the weapon has a removable handle (simply locked by a flat spring): it can be positioned at two points (Pics.25 and 26):

- On the center of gravity of the weapon (at the front of the rear sight), which makes it possible to move (and position) the weapon alone.

- At the front sight level: which makes it possible to transport the weapon in pairs: one by the carrying handle, the other by the stock.

And the device is rather conclusive: when there’s two people, the weapon is moved quickly and without too much difficulty.

Finally, the weapon can be instantly disassembled into two bundles: a strong key is arranged at the front of the receiver (Pics.27 and 28). Its removal is extremely simple (press its lock button and tract it). Paradoxically, the weapon is probably not easier to carry on foot in this configuration: the use of the handle is much more convenient. On the other hand, it is easy to guess the logistical advantage of not having to have a box of more than 2 meters for the packaging and transport of the weapon from the factory or warehouse … it even fits in a SEAT Ibiza… Similarly, the cleaning, especially of the chamber, which is a sensitive point, is greatly simplified by this possibility (Pic. 29).

Simple mechanics, prefiguring the SKS-45

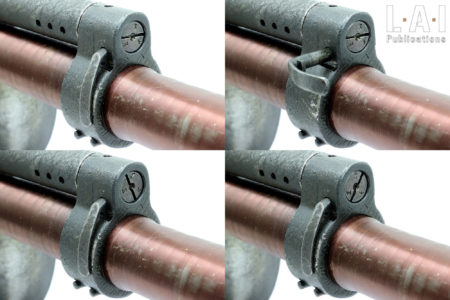

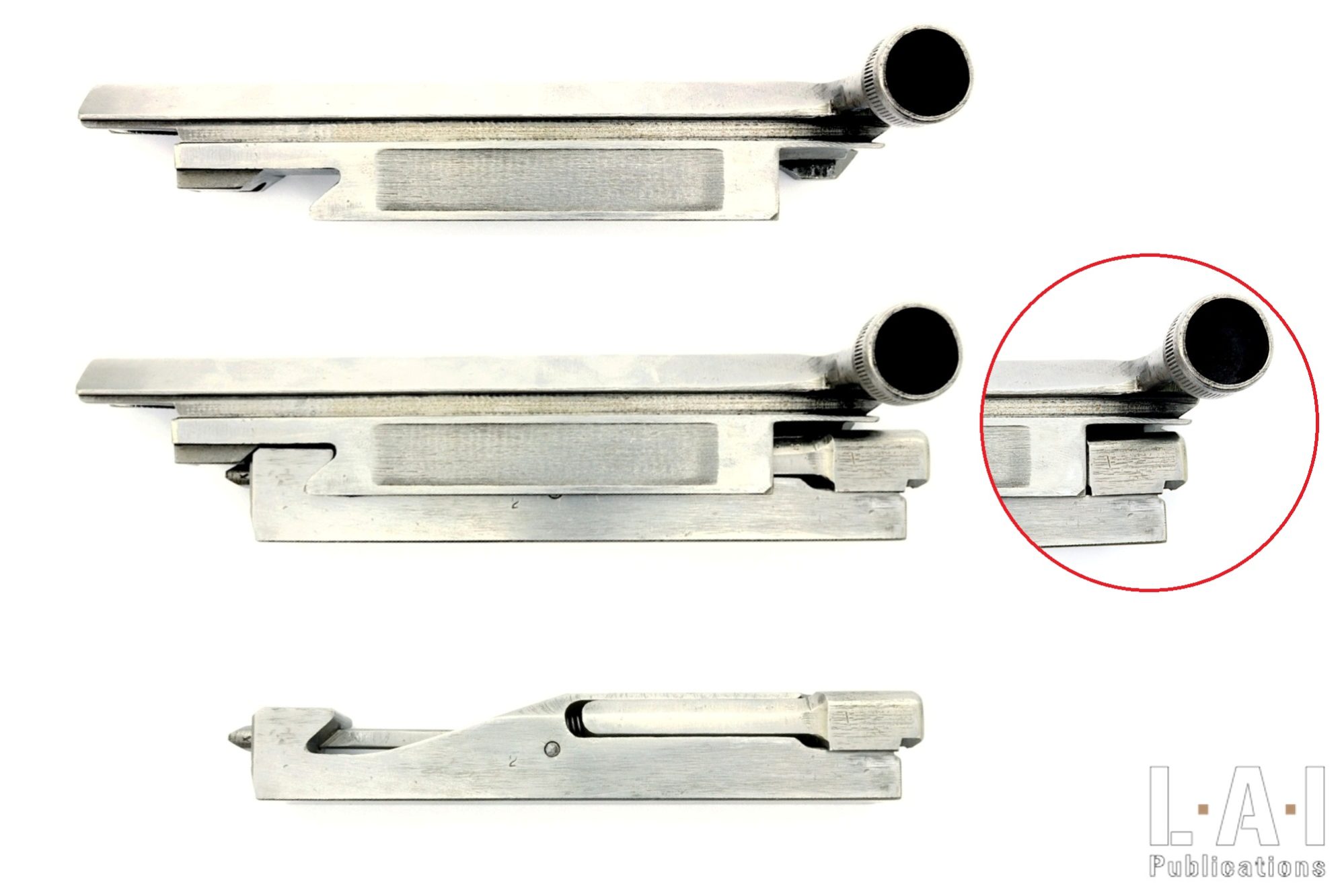

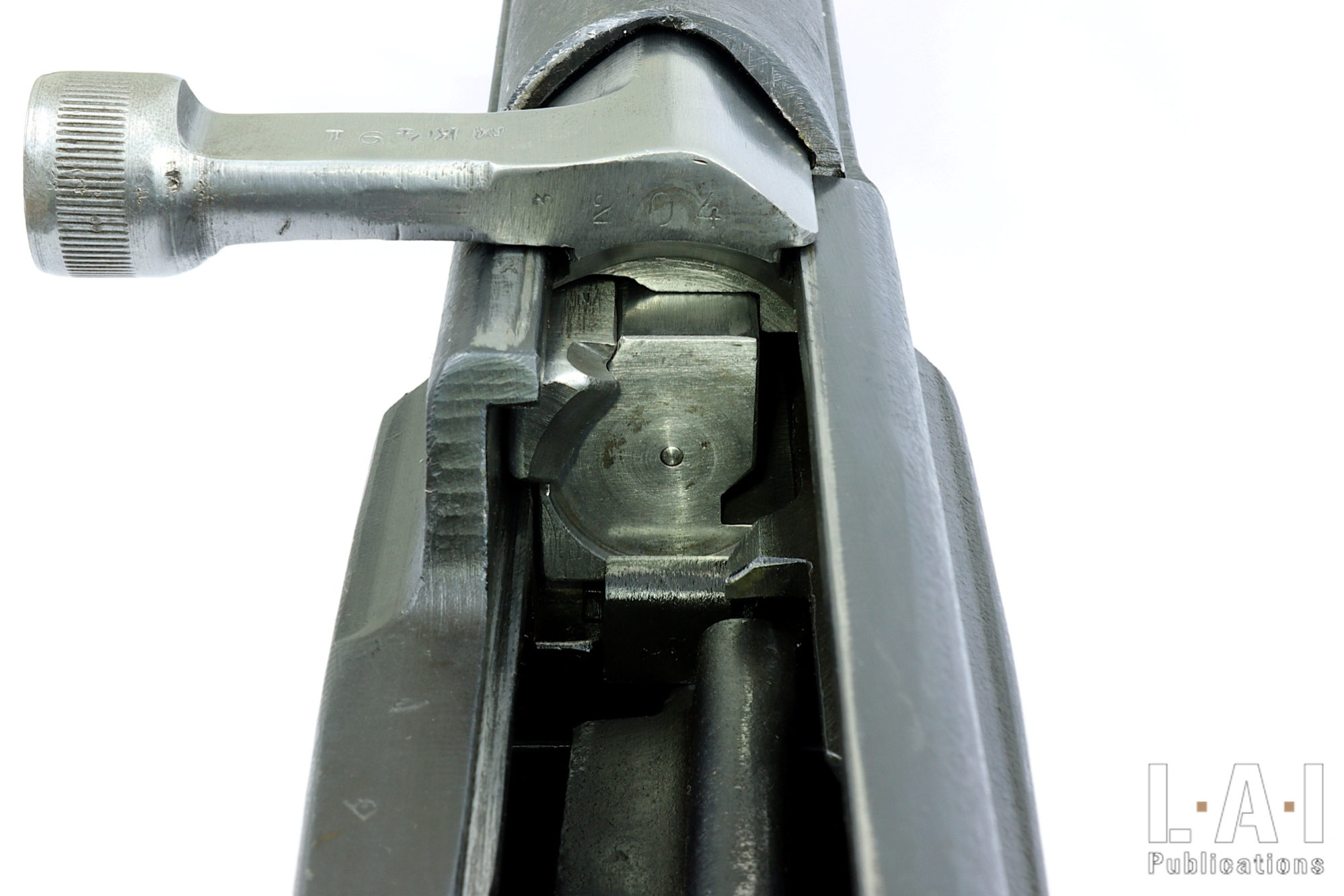

For his semi-automatic anti-tank rifle, S.G. Simonov took up the operating principle of his 1938 semi-automatic rifle in 7.62×54 mm R. This is a prototype made as part of the competition that saw the adoption of the SVT-38. There is therefore a gas system with unlinked piston and short stroke associated with a tilting breech (Pic.30 and 31). The gas block has a three-position intake regulator, which allows the weapon to be adapted to its working environment (Pic.32). The massive ejector is machined directly into the receiver: the power of the ejection is therefore dependent on the cycle-rate, and therefore on the position of the gas regulator (Pic.33). The extractor is carried by the breech. Positioned on the right side, it is closely followed by the breech carrier which restricts its stroke according to the position of the moving assembly. Locked, it is immobilized, unlocked, it has the stroke necessary to “jump” the rim of the cartridge when closing (visible in Pic.30). The feeding is not controlled: this provision is also seldom seen on Soviet weapons with the notable exception of the TT-33. Similarly, the absence of a rotary lock prohibits the use of primary extraction, something which would have been very useful on such a weapon.

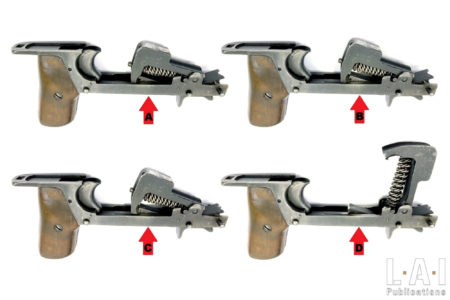

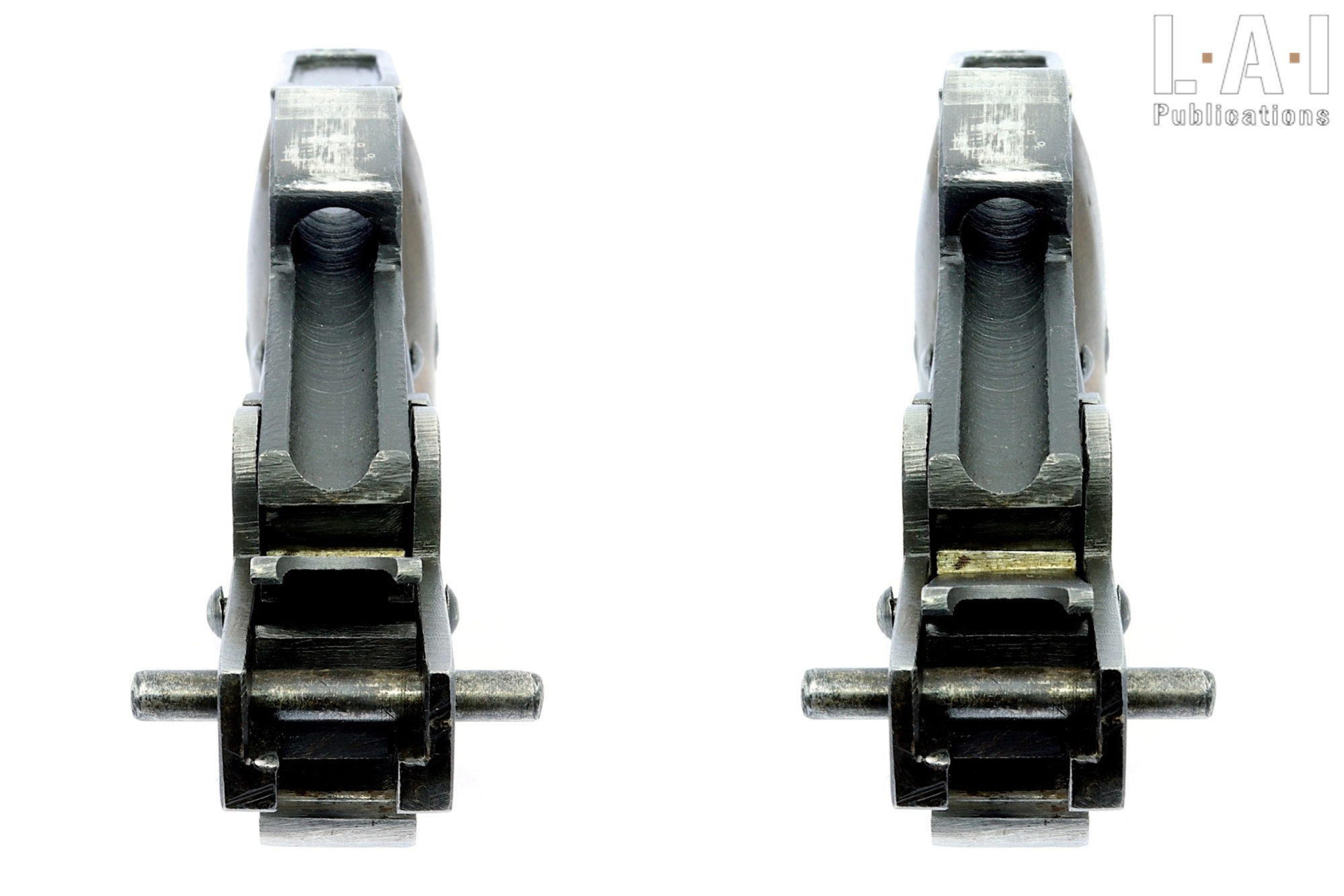

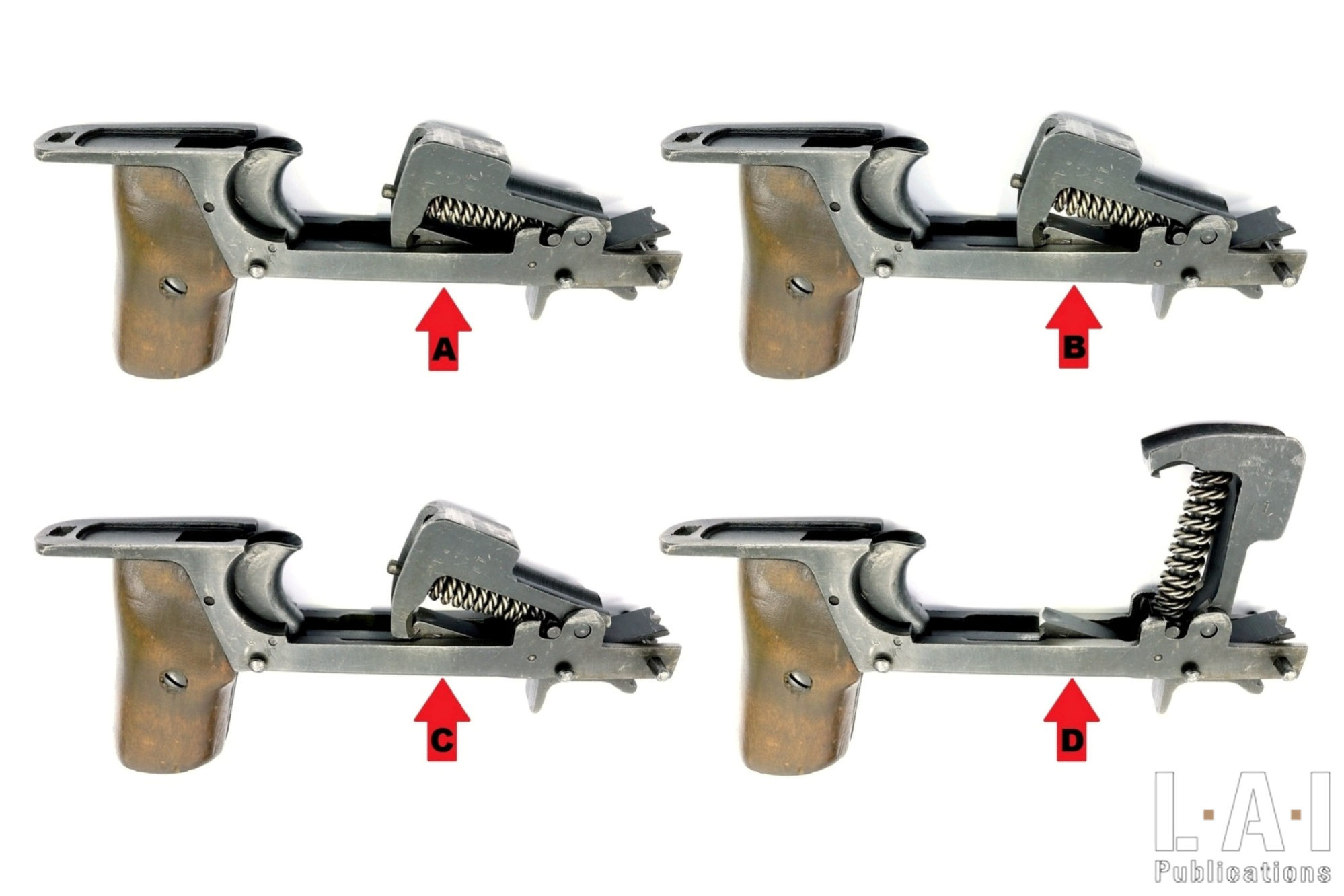

The trigger mechanism is mounted on a removable frame (Pic.34). It uses a classic hammer with circular motion. It is subject to a safety sear working at his base. In a skillful way (because there are few parts), this safety sear performs two functions:

- Safety at closing. To do this, it is operated by the breech stop, the upper end of which protrudes into the lower part of the locking recess. This real safety at the closing is therefore controlled by the collapse of the rear part of the breech during locking: it must be kept in the low position by the locked breech so that the hammer is free. It should be noted that this safety system is based on the use of two notches on the main sear: in case of pressure of the trigger a first time without a locking breech, the hammer is held by the safety sear between the two notches of the main sear (Pics.35 and 36). Therefore, when the breech is locked, it releases the hammer that comes to hang on the second main sear notch. Thus, the system has a weakness: if the breech is unlocked while the hammer is hooked by the second notch of the main sear, then it is possible to trigger down the hammer. Fortunately, even if this manipulation – however small the chances may be to actually perform it at all…you don’t “tap-rack-bang” such a weapon…at least I hope so for the user… – occurred, the hammer falls, depending on the stroke of the BCG, either on the classic “rounded” breech edge, or on the breech carrier. This also ensures that the breech is in the locking position before the firing pin is accessible. However, aware of this “weakness”, Simonov would modify the system on the SKS-45: this safety at closure would then work on the connecting rod.

- Safety of the magazine latch. Actually, the thing here reverses the function: instead of prohibiting the shot, it is therefore impossible to open the magazine (because the latch cannot move back) if the breech is locked. To supply the weapon, it is therefore imperative to put the BCG at the rear to release the movement of the breech stop.

The main sear (i.e. the one operated by the trigger), which works on the hammer’s crest, is of a “drawer” type (i.e. it slides instead of rotate) and therefore has two notches to accommodate the operation of the safety sear. It is implemented by a connecting rod that is disengaged downwards by the hammer’s crest during rearmament: separating the trigger from the sear, the semi-automatic fire is thus created.

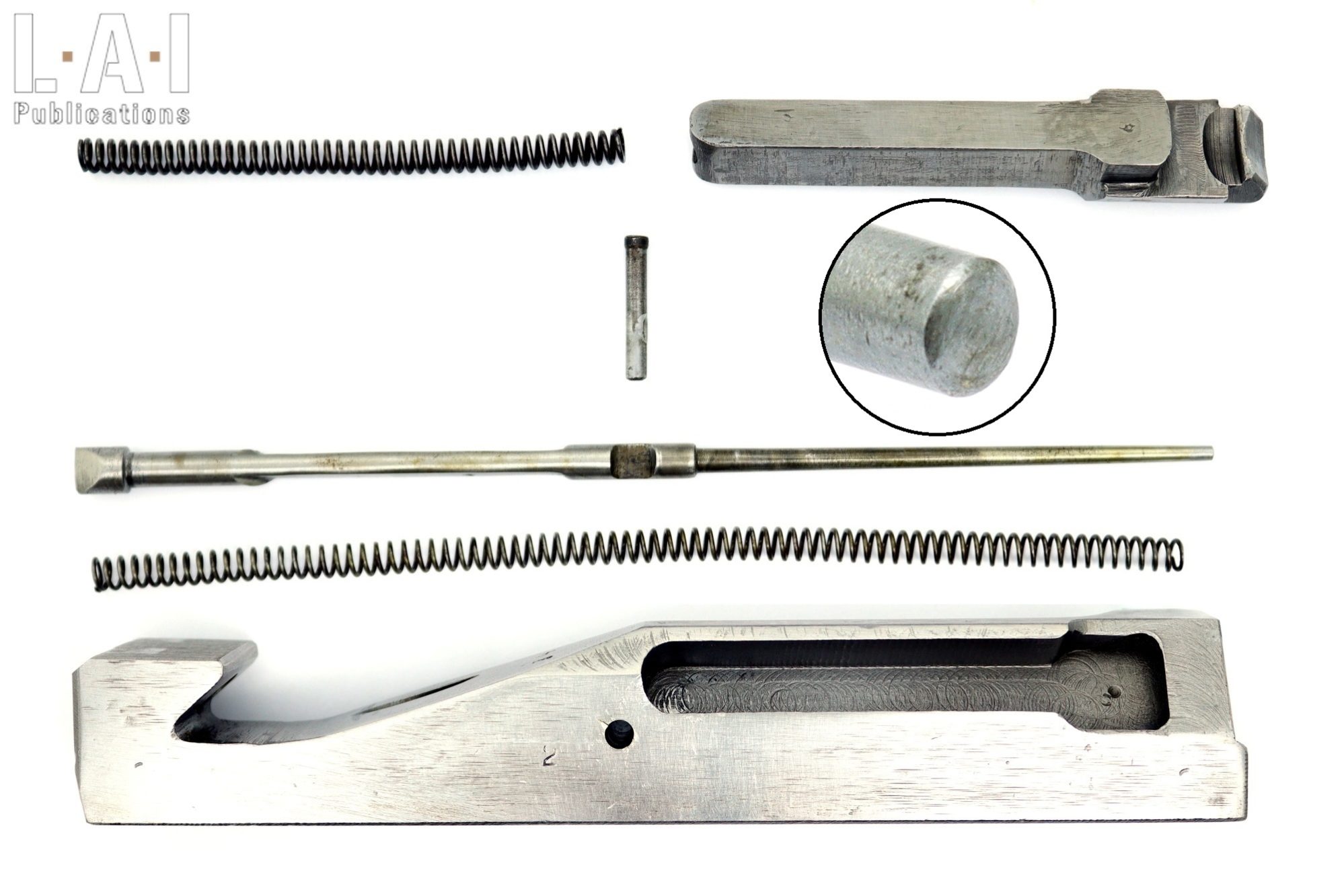

The firing pin, carried by the breech, is of the “hit and press” type. It has a strong return spring, which associated with the particularly flattened shape of its tip is intended to avoid departures on the inertia of the closure (“slam-fire” Pic.37). And indeed, the fear is justified: the firing pin is massive (24 g) and must therefore have a significant inertia at closing. Furthermore, the firing pin is machined so as to stop on the breech carrier when the BCG is in the unlocked position: it reproduces the inclined plane controlling the locking/unlocking (visible in Pic.30).

The feeding system therefore consists of a large cavity intended to accommodate the clip, closed by a large forged and machined steel lid! A quite imposing part to say the least that makes us relativize the idea that this would have allowed to “lighten the weapon”. As already mentioned, the lips are machined on the receiver. The follower, articulated on a long rod, finds its rising force on a short coil-spring arranged at the base of the rod (Pic.38). This provision – which like many provisions of the PTRS-41 – would be reproduced as is on the SKS-45 is not without questions (an article is to come on the SKS-45). Its disadvantage: it positions the spring in a mechanically unfavorable position in its role (at the base of the fulcrum in a lever system) … But it also has advantages. The spring is short (therefore inexpensive) and well protected (therefore not very sensitive to fouling). All in all, with a spring of a high power, this choice may seem rational … but surprising.

The construction of the weapon mainly involves machining and unlike V.A. Degtyarev’s weapon, many milling operations and few lathing (barrel excepted…of course!), most of the parts being of a very “parallelepiped” shape. The whole is realized, in the usual way in the USSR, with quality, but without ostentation. The finishes are raw where it doesn’t matter… and good where it counts. Think different. The materials seem of quality: despite its age and the shots drawn, there are little to no traces of wear! All the pieces are hot blued, with the exception of the BCG which is “white-polished”, something classic for moving parts. The eggplant color of the barrel? This is classic when bluingSurface finishing of steel giving a black (sometimes bluish)... More parts made of high alloyed steel… which seems to be the case with this barrel!

Shooting

To start, the video from “Le Feu aux Poudres” channel, an excellent introduction to shooting with this weapon:

So, let’s be clear: personally, I don’t like to shoot weapons of this type, whether in 12.7×99 mm or 14.5×114 mm, no more than I like to shoot a lightweight 12-Gauge shotgun… No, I’m not a masochist. In addition to the problem of recoil (we’ll talk about it again), the sound volume (even with protection) and the blast effect are unpleasant and, for me are enough to break the pleasure I have when shooting. Regarding the recoil, the thing is rather surprising, because if the rifle recoiled deeply, it does not really do it violently: the weight of the weapon, the muzzle brake and the padded layer plate are at work. Thus, it twists your body more than it hits it… (there is a little anecdote at the end of the article for the greediest among you). But the thing remains bearable, and the shots finally go on one after another rather easily for those who like this … or those who have no choice.

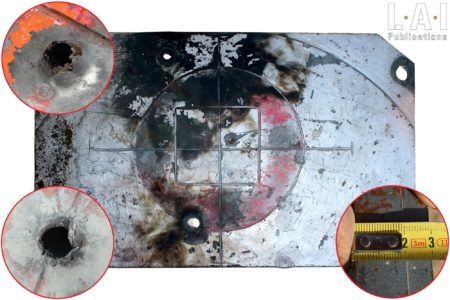

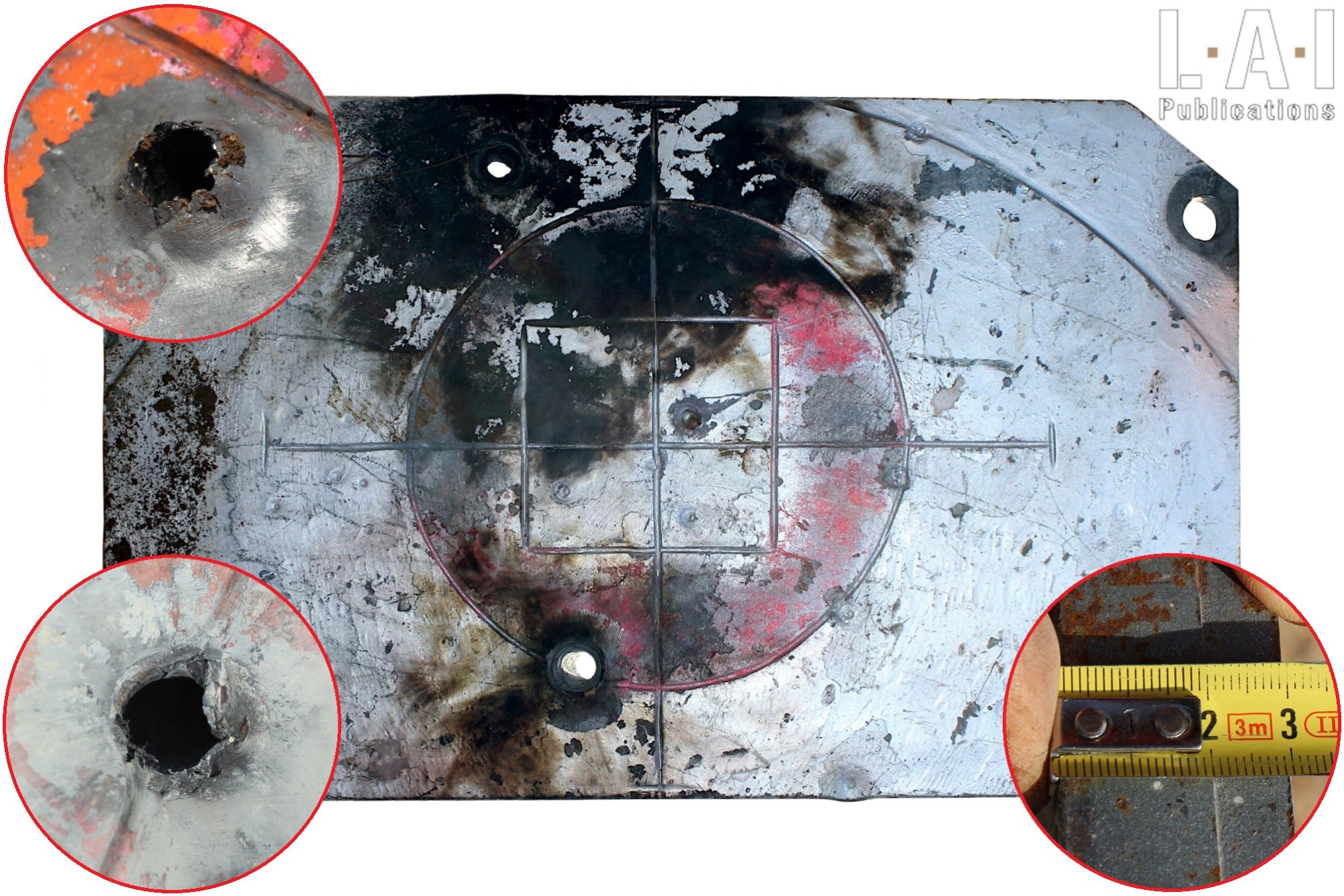

Because of course, the performance of the beast is only interesting from a military point of view: we do not do sport shooting. And there, clearly, it is bluffing. We had the opportunity to supervise tests / demonstrations of the weapon on several shooting sessions (of which the video below is a sequence medley) with several shooters at distances up to more than 1200 m. The first observation is simple: the implementation of the weapon is rather simple and fast … as long as there are two people managing the machine. Whether for transporting, setting up, loading or resolving shooting incidents, being alone confers, from our point of view to operational suicide. But together, everything goes smoothly: the shooter being relieved of the “logistical” aspects, he can devote himself to his work. And the pair is not to be outdone in this work: supplier, loader and spotter… essential. The role of spotter is primordial: the weapon moves too much to allow the shooter to see his shot. But the result is clear: even with little practice of the weapon, the effectiveness is there. The firepower (the real one, the one that makes a shot / a goal quickly and repeatedly) is there: on a target the size of a vehicle, the shots are easily at the goal … up to 1275 m which is the maximum distance at which we shot… on an AMX-13 VVT (APC version) presenting its back! At this distance, the tank wreck is not pierced, obviously… We are beyond the practical capabilities of ammunition on this type of vehicle… But we are still on target! At 400 m, a smaller target (here a 51 x 31 cm steel plate) is easily reached after a few tests, which shows that it is even possible to reach a particular area of the vehicle (Pic.39). We think here that the recommended ranges of use were then 250-300 m maximum. The hit probabilities are therefore very high… Probably much higher than with a rocket launcher, even on a moving target. The sights are clear, and the departure, as usual among the Soviets, of a sliding type (Pic. 40).

Regarding terminal efficiency, we only carried out demonstrations and not advanced ballistics tests. However, we have seen comparative tests between the calibers 12.7×108 mm (B-32 ammunition), 14.5×114 mm (B-32 ammunition) and 23×152 mm B (BZT ammunition – API-tracing) … And in some situations, the 14.5×114 mm is the most effective ammunition in terms of perforation! Some situations, because in terminal ballistics, there is usually not “a truth”, but rather “circumstances”.

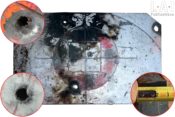

On our side, the steel plate of about 30 mm thick was pierced at 400 m without any difficulty by both Chinese and Soviet B-32 type ammunition. If the exact composition of the steel is not known, it is quite likely that it is some kind of Hardox.

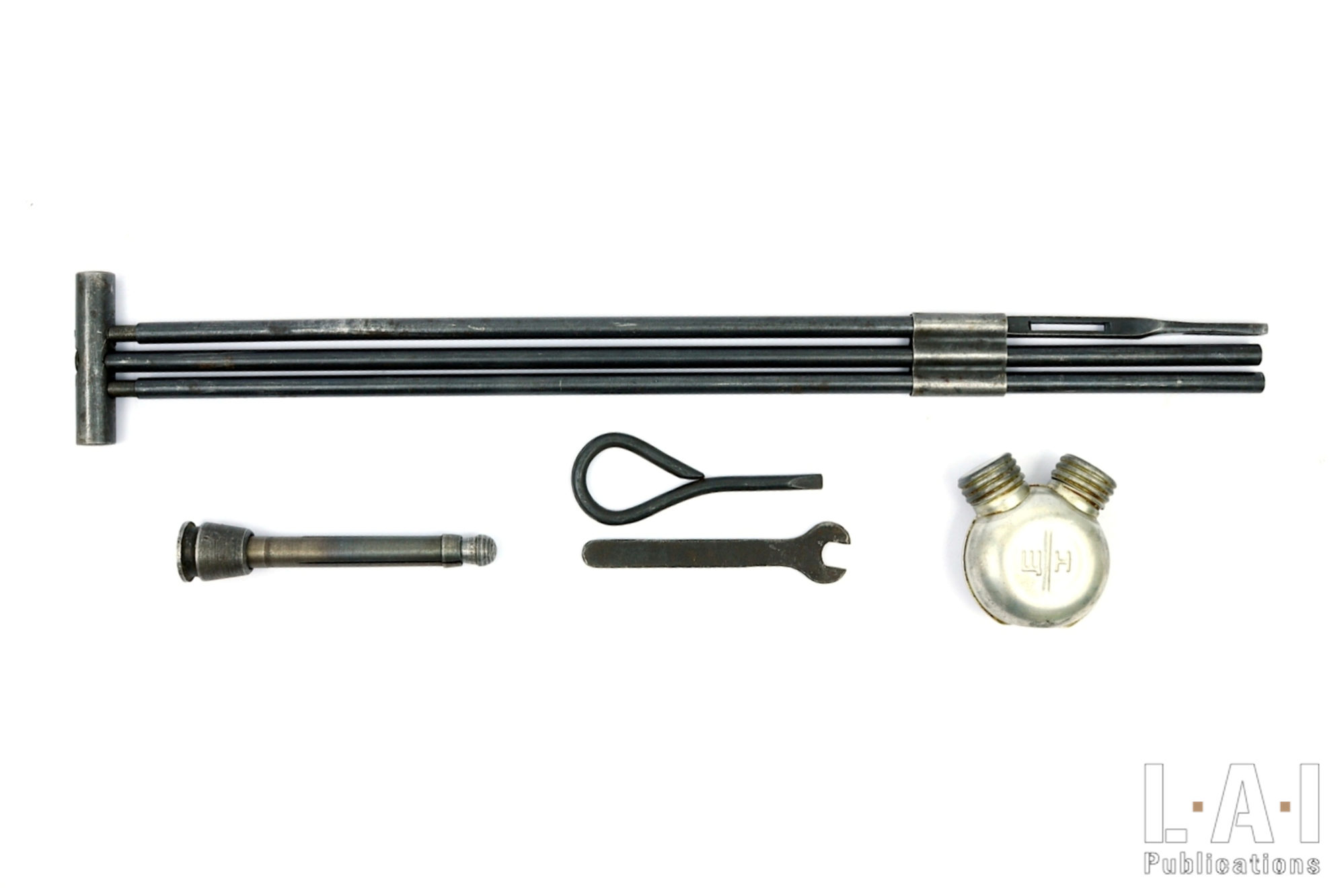

So obviously, faced with the use of this weapon manufactured in 1944 (and not always maintained as it should have been…), we encountered several shooting incidents. This was mainly related to the poor condition of the chamber (oxidation of the forward portion of the chamber resulting in case sticking that can generate complete extraction defects, but also case head separation – Pic.41) and the weakness of the springs (percussion defect, malfunction of the breech stop). But it was a good for a bad thing: it allowed us to experiment with methods of solving incidents of live fire, including the use of the broken shell extractor (a service accessory…provided for good reason!) … and the service steel rod, absolutely necessary to remove a case whose rim was sheared off by the extractor (Pic. 42). So, let’s be clear, for the use of the broken shell extractor, once it is positioned in the chamber, the opening of the BCG is done …, in a lying position, kicking on the cocking handle! A crew-served weapon… Finally, remember here that faced with a non-start of a shot, it is necessary to wait a long time in firing position in order to guard against the negative consequences of a hang fire. The waiting time varies according to the doctrines, up to 2 minutes and more. It seems long behind the weapon but is nothing on the scale of a lifetime. The risks of a hang fire with this type of weapon? Well, very simply: death. Just imagine that you have unlocked the mechanism and that the shot goes off… It’s worth the wait! And this type of accident exists, 12.7×99 mm is even enough to cause real deaths.

Disassembling and maintenance

Like its direct descendant, the SKS-45, disassembly, and maintenance of the PTRS-41 is exceedingly simple (video available at the end of the paragraph).

After checking that the weapon is clear, proceed as follows:

- The BCG is positioned forward.

- The assembly key is removed from the barrel.

We end up with two sub-assemblies: the barrel and the receiver.

For the barrel group, we proceed as follows:

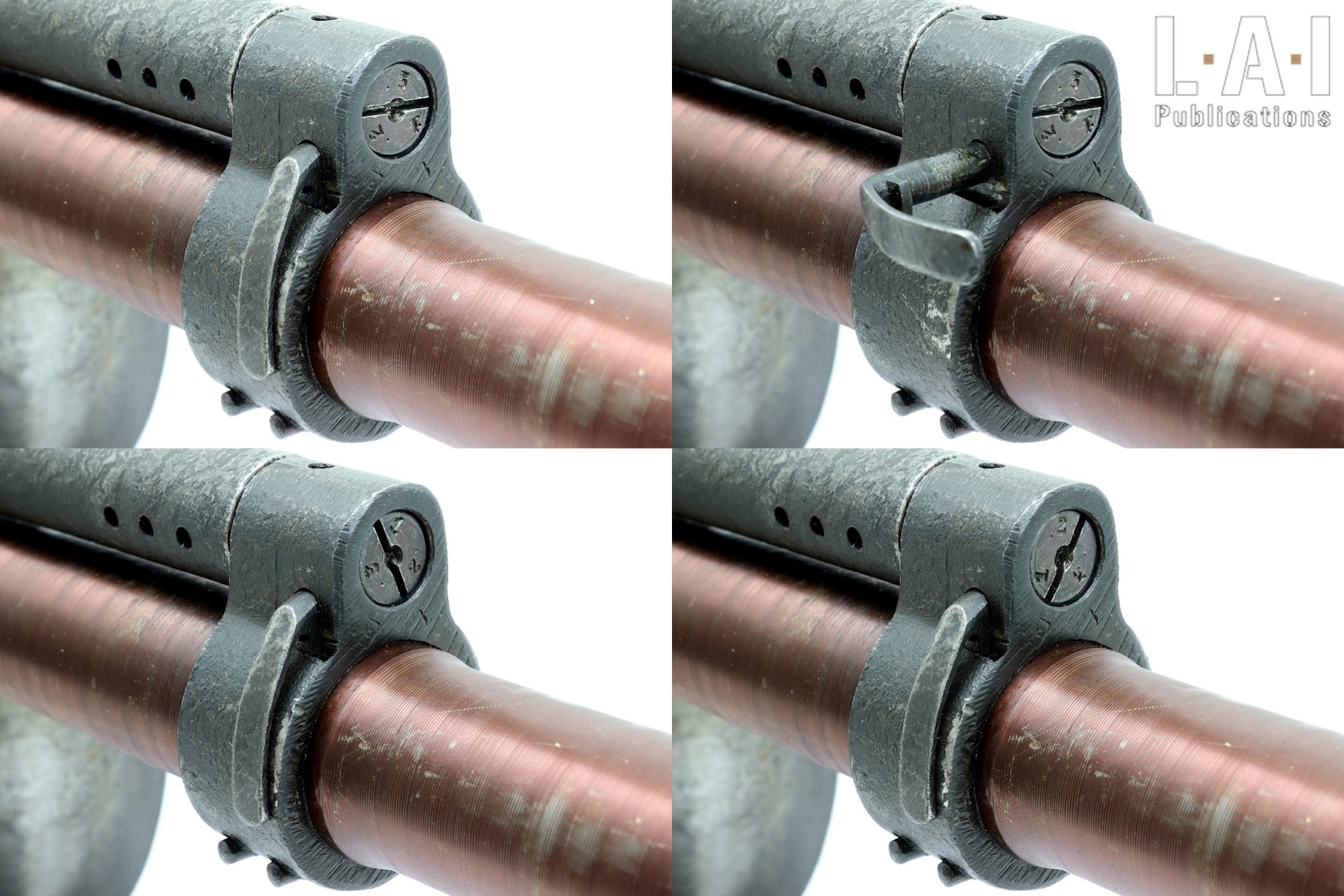

- Rotate the gas nozzle key forward, then remove it from the right side.

- Using a suitable tool, push the gas nozzle into the tube until it extends beyond the rear end of the gas block and holds it in that position. Therefore, it is possible to lift the front part of the gas tube, taking care not to eject the nozzle and piston as soon as they are no longer constrained by the gas block.

- Remove out by the front of the tube, in order, the nozzle, the piston and the rod.

- Release the rear part of the tube: then extract the breech carrier pusher and its return spring.

The barrel group is disassembled.

For the receiver group, the procedure is as follows:

- With the BCG at the front, rotate 90° counterclockwise the disassembly key on the right side of the rear part of the case, then extract it from the weapon.

- Lift the back of the breech cover, and while accompanying it, remove it from the weapon.

- If the return springs assembly did not come with the breech cover, remove it from the breech carrier. It consists of three elements: two identical springs and a central guiding rod. These elements are simply nested.

- Pull the BCG towards the back of the receiver.

- Remove the breech carrier, then the breech itself.

For a little more thorough disassembling, the firing and feeding systems can be removed as follows:

- Using a screwdriver (there is one in the weapon’s accessories), unscrew the screw on the back of the lower part of the receiver. This has a particularity: a stop spring needs to be pushed back when the screwdriver is placed inside the slot. This arrangement makes it possible to avoid untimely loosening when shooting (Pic. 43).

- Once the screw is removed, lower the pistol grip and then pull the trigger mechanism towards the back of the weapon. By taking the trigger mechanism out of the weapon, the feeding system opens and can be extracted from the receiver.

- On the trigger mechanism, the protective flange can be removed from the top. The removal of this flange gives access to the different axes of the trigger mechanism. It is noted that without further disassembling of the trigger mechanism, the accessibility for cleaning is excellent here.

Here we arrive at the end of a “field” disassembling, rather pushing, which offers excellent accessibility for cleaning (Pic.44).

The greediest can add the disassembling of the trigger mechanism, the breech and the breech stop in order to achieve an “advanced” disassembly.

For the trigger mechanism:

- Position the hammer down. To do so: press the trigger a first time, then press the safety sear and finally press the trigger again while accompanying the decompression of the hammer. Be careful, it pushes a little bit…

- Maintaining pressure on the top of the hammer, chase its axis. The hammer comes out with its spring and guiding rod.

- Remove the safety sear axis: the part can be removed upwards from the frame.

- Extract the main sear’s spring (which also activates the safety sear).

- Push the main sear towards the front of the plate: it can then get out from its housing.

- Chase the axis of trigger. This can then be removed from the frame.

- On the trigger, chase the axis of the connecting rod. This can then be removed from the trigger.

- On the trigger, remove the trigger axis’s spacer, which holds the trigger/connecting rod return spring in position inside the trigger.

- Remove the pivot axis from the frame (which holds the magazine latch), then remove the magazine latch and its spring.

- Finally, on the protective flange, it is possible to remove the safety as follows: go beyond the “firing” position (forward) until the retaining rod present on the safety’s axis in front of the opening of the flange is matched, then extract it from the right side.

For the breech:

- By pushing the extractor into its housing, pivot its front part outwards: the extractor comes out of its housing accompanied by its spring.

- Keeping the firing pin heel under pressure, extract the firing pin pin (which is shouldered) from left to right. It is not necessary to extract it completely: it is simply necessary to push it back enough to be able to extract the firing pin and its spring.

Finally, for the breech stop:

- Remove the breech stop pin from the receiver.

- Remove the breech stop by the lower part of the receiver.

- Remove the breech stop spring.

The disassembly of the weapon can be considered “complete” at the user level. The reassembly is done in the opposite direction (Pic.45). No particular difficulty, only a few parts really, no small or fragile parts: the weapon is therefore particularly adapted to its destination. The unlinked piston gas system works wonders when it comes to fouling compartmentalization: the receiver is contaminated very little by firing.

In conclusion

The PTRS-41 remains, even today, a weapon with impressive capabilities that prefigures among the modern anti-materiel rifle. Obviously, in anti-tank warfare, these piercing capabilities clearly cannot be matched by the HEAT charge (or charges) carried by a shell, rocket or missile. But the weapon shows capabilities that even today justify its sporadic use on the battlefield, where necessity is law. In the end, given its level of firepower, the weapon is maneuverable, easy to deploy and camouflage. Thus, while it will be powerless against a modern “MBT”, if well-served it would still pose a threat to many light vehicles and many poorly fortified shelters. From a technical point of view, it foreshadows a weapon that would mark the Soviet Union almost as much as the Kalashnikov: the SKS-45. But that’s another story…

Arnaud Lamothe

Selected bibliography:

« Soviet small-arms and ammunition », David Naumovich Bolotin, Finnish Arms Museum Foundation, 1995.

“ Munitions militaires russes pour armes légères 1868-2008 “, Philippe Regenstreif, Crépin-Leblond, 2007.

For service manuals (consulted on April 3rd, 2023):

For the cross-checking of certain information:

https://modernfirearms.net/en/

Obviously, for different numerical sources, especially related to vehicles; different Wikipedia pages (consulted from March to April 2023).

Are there any readers left? Ready for the osteopath’s anecdote?

As stated before, shooting this kind of weapon is not my passion. So, I tried it for the first and last time in 2015. I fired two rounds… and left my place to comrades greedier than me for this kind of adventure (some have fired several dozen shots during the same session … greedy I tell you!). Sometime later, without immediately making the connection, pains gradually appeared in my forearm and left hand. The thing getting worse over time (loss of grip, sharp pain waking me up at night…), I naturally went to my doctor, suspecting an onset of carpal tunnel syndrome, an existing condition in my family (yes, today, I am telling you about my life… even if you don’t care!). A battery of tests followed, including a cervical MRI and electromyography (connoisseurs will appreciate) without any diagnosis being made. Faced with pain and yielding to the entreaties of my partner (a Saint, no doubt about it… she bears with me), I end up going to see an osteopath that a friend (the same one who acquired this very weapon… curious coincidence!) advised me of. I must admit that I was skeptical. During the consultation, the thing was obvious to her: I had suffered a violent “blow” that had affected the top of my spine and explained without a shadow of a doubt my pain. After having “manipulated” me (crack!), she gave me an appointment 2 weeks later for a second session (for free!) to perfect the work, too “severe” to be treated in one session. This story of “blow” slowly made its way to my mind during the session, and I was wondering about its origin … My physical activities are not particularly violent, besides cutting wood… But the memory of the shooting session came back to me. And during the second session of osteopathy, I presented my witch a video of the shooting… And indeed, the back “twists” when shooting, especially if you tend to have a too angular position with the weapon. For her, the connection was obvious. And yes, the osteopathy sessions (re-crack) made the pain disappear … Since then, the visit to my talented practitioner is regular! Obviously, no more shooting at PTRS-41 for Nono (it’s me!): the role of assistant gunner suits me very well!