STG 44 & FG 42 : origins and legacies

When we look at the history of individual small-arms, the main legacy of the WWI is undoubtedly the emergence of the “submachine gun”. Although his appearance was notable, his integration into the armed forces was ultimately timid. In fact, it took place on the margins of the more decisive use of crew-served weapons: the intensification and rationalization of the machine gun, and the culmination of the concept of the light machine gun. Thus, the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More was finally adopted on a massive scale by the belligerents of the WWII shortly before the outbreak of the WWII… even during the war for some of them! Concerning the WWII, individual small-arms were very marked by two weapons, both German: the “FallschirmjägerGewehr 1942″ and, what would eventually become the “Sturmgewehr 1944“.

(Because our English corrector is not actually available, the following version has been translated and corrected only by me, the author. English being clearly not my native tongue, I apologized here for the mistakes you will encounter).

Conceptual origins: a similarity and many differences

The origins of the FG 42 and the STG 44 weapon family have one thing in common: the need they meet. Indeed, both are individual automatic weapons with selective firing mode. And in both cases, the primary use of the weapon is semi-automatic fire for an adjusted shot. In both cases, the idea was to increase “firepower” at the individual level at a time when the manual repeating rifle (or more rarely, semi-automatic) was the basic armament of the infantryman.

It is necessary here to define the notion of firepower, or at the very least, to propose a “vision” of the thing. As mentioned in the article “Some Thoughts on Burst Fire”: from our point of view, firepower is the ability to hit targets (of a specific type) with a destructive capacity in a repetitive and rapid manner. So, when you increase the “firepower”, you increase all this by making appropriate choices and you gain in efficiency (especially with regard to the number of ammo consumed). In our view, it must be distinguished from the concept of “volume of fire”. The latter consists of saturating the combat zones of one’s choice with fire without worrying about the “efficiency” aspect in terms of assessment, but only to consider the tactical openings that this allows. Of course, these two concepts have very different logistical and practical implications. It is interesting to note that Hand-Dieter Handirch’s book “Sturmgewehr!” published by Collector Grade Publications is subtitled “From Fire-power to striking power“, which also leads to a reflection in this area. Finally, we have chosen here to specify “by appropriate choices”, because these choices must encompass all the implications on the military system, logistics at all levels included (from its manufacture to its distribution). A notable example in the subject at hand is that the power of the caliber and ammunition used must be “right”: not too much, not too little, just enough to destroy a target of a given type at the distances envisaged, without involving unreasonable logistical considerations.

On the other hand, it is obvious that beyond this common original need, the two weapons are ultimately very different. Among these differences, we can first raise here the problem of the users initially targeted by each weapon: they are not the same. In addition to the airborne vocation of the Fallschirmjäger (German paratroopers under the command of the Luftwaffe, the Air Force), it can be noted here that they are assimilated to what some would call “elite” troops. We don’t like the term “elite”, we prefer the term “specialized”: they have a different job. Less numerous than “ordinary” infantry units, it benefits from a different selection and training, which can be considered objectively more demanding. It should be noted that the German paratrooper units had a specificity compared to many other armies: that of jumping directly on the enemy’s positions, and not at a distance from them. This specificity therefore required to jump “in arms”, with armament ready for a consequent response, without having to “recover” the usual containers that carried the “heavy” armament (of which the K98k was a part) to the drop zone. Thus, during Operation Merkur, the Fallschirmjägers had jumped with 9×19 mm pistols and submachine guns as their only armament immediately at their disposal. For its part, the STG 44 family was designed as a weapon intended for more “ordinary” infantry troops.

This first difference is palpable on the weapons themselves: they were obviously developed from a rather different reflection:

- The FG 42 designed by Louis Stange (and produced by the Kriegoff firm), is a light machine gun transformed into an individual weapon, in particular by its lightening and the optimization of the results in single mode by firing from a closed bolt. Indeed, the FG 42 firing from a closed bolt in single, and from an open bolt in automatic firing (the difference is explained in chapter 6 of our book “Small Guide for Firearms” available on our website and in link here).

- The STG 44 family weapons designed by Hugo Schmeisser (and produced by the Haenel firm), and especially the pre-series MKb42(H), is between the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More and the light machine gun. If, at the beginning of their designs, the weapons of this family were presented to the German authorities as a SMGSubMachine Gun More, or even as a “heavier” SMGSubMachine Gun More (Schewer-MaschinePistol or SMP) and then as “MaschinenKarabiner”, this is quite clearly in our opinion a “conceptual trial and error”. Creating a new category of weapons with a new category of caliber, everything had to be thought of. So this trial and error seems quite natural to us. Subsequently, the return of the “MaschinenPistol” designation was only intended to continue its development in the face of officials hostile to the replacement of the 7.92×57 mm IS in the infantry weapon by a less powerful ammunition. Here again, the problem of firing from an open bolt (favouring burst firing) or closed firing (favouring single) has led the weapon to several versions: first firing from an open bolt in both firing modes, the weapon definitively adopted will only fire from a closed bolt.

Immediately after this first consideration, we note that the two weapons make a choice of very different calibers (Pic.05):

- The 7.92×57 mm IS, the “standard” caliber of the infantry rifle (then the K98k) for the FG 42: this choice is a priori a mixture of at least two motivations. The first is probably the feedback, or even the “trauma”, of Operation Merkur in Crete. Although this battle ended in a German victory, the Fallschirmjäger had suffered many casualties and had been put in difficulty by the heavy fire of the British Empire’s soldiers at long range, especially by their BREN LMG. The second motivation was the obstinacy of certain dignitaries of the Nazi regime to keep the 7.92×57 mm IS as the main service caliber. In a rather consensual way in the specialized literature, Hitler himself would have decided for a long time in this direction. One may also wonder whether a certain analysis of the logistical consequences (difficult to judge objectively more than 80 years later…) of the introduction of the German arsenal could not seem more than legitimate. Although the 7.92×33 mm was more economical to produce, the 7.92×57 mm IS did not only have flaws. In service for several decades, German industry was very comfortable with it and it would still be needed to supply crew-served weapons, on-board weapons and sniper rifles in any case. Introducing a new caliber is always a risk. Doing so during a war, when supply chains are crucial and already under strain, is obviously even riskier. Moreover, the Soviets did not venture to put into service the 7.62×39 mm, the studies for which began in 1943, until a few years after the war. It should be noted here, so as not to open the way to hasty shortcuts (young hobbits!), that the reflection on the reduction of the power of infantry ammunition in Imperial Russia / USSR began before the WWI. A great deal of work in this field took place before that launched in 1943 and which culminated in the adoption of the 7.62×39 mm in 1945. We’ll come back to that later in this article.

- The 7.92×33 mm “Kurzpatrone” (short cartridge) for what would become the STG 44. Here, the development of this new caliber was based on the reflection of “useful power” in combat up to 600 m (“maximum” distances evaluated by both the Germans and Soviets to determine the ballistic effectiveness of their intermediate calibers). The basic thinking is fine: the 9×19 mm is undoubtedly insufficient and the 7.92x57mm IS is objectively “too powerful” for many reasons. Among these reasons, the adoption of a less powerful caliber allows the weapon designer to produce weapons that are more economical from a production point of view at a time when the difficulties in the supply of quality steel are real. Here, we are in the realm of pure and hard pragmatism, that of observation. It can be noted here that the “exact distance” from the field of use of intermediate calibers can be debated, but up to 300, 450 m and even 600 m to go as far as possible (in our opinion, too far), we are talking about the same thing overall.

The 7.92×33 mm caliber is the most interesting design aspect of the STG 44 family. It is undoubtedly innovative in the sense that it is the first intermediate caliber actually adopted by an army.

An intermediate caliber can be defined as a caliber whose external and terminal ballistics characteristics fall between the calibers usually used in handguns (and used incidentally, because logistically available, by submachine guns) and the calibers of infantry rifles, which could be described as “ordinary” (some will say “full power”). Ordinary because it was used by the majority of industrialized nations before the start of WWII. These calibers were then used in their infantry rifles, machine guns and machine guns. Compared to “ordinary” calibers, intermediate calibers offer several advantages:

- From an industrial point of view, ammunition is less expensive to manufacture because it is more economical in terms of raw materials.

- From a logistical point of view, they are lighter. This will have an impact on the supply chain at all levels: from the train to the soldiers, for the same mass, we carry a greater number of shots. In the case of the 7.92×57 mm and 7.92×33 mm, the Kurtzpatrone is about 30% lighter. This logistical benefit leads to an obvious tactical benefit, which is not the least: soldiers will have more shots to fire in combat with the same mass.

- From a “gunsmith’s” point of view, the use of less powerful ammunition allows for the design of weapons that are less resource-intensive, as they require less robust mechanisms, including with semi-automatic and automatic weapons. This advantage leads to another: with equivalent characteristics, these weapons are necessarily lighter than weapons of higher calibers. A real advantage for the soldier who spends most of his time carrying his rifle and not shooting with it.

- From a tactical point of view, in addition to the logistical advantage already presented, weapons produce a much lower recoil than weapons in “ordinary” calibers. Thus, they are easier to control with shooting, in single as well as in bursts and therefore make it possible to maximize the hit probabilities, especially with less trained soldiers.

The downside, because you need one: it’s the “loss of power” of the ammunition, of course. This will restrict the practical range of the weapon and the ability to engage “protected” targets. But in reality, this “long-range” work (meaning here in our opinion, from 500 – 600 m) and “anti-material” (meaning here, a very lightly armored target or behind a light cover) does not really concern the non-specialist infantryman (understand here, who does not use crew-served or specialized weaponry such as a sniper rifle or anti-material means).

Here, it is important to dispel preconceived ideas that were sometimes encountered: no, the 6.5×50 mm SR Arisaka and 6.5×52 mm Carcano are not intermediate calibers (Pic.06). By the same token, no, the V.G. Fedorov and Cei-Rigotti automatic rifles are not assault rifles. For the Cei-Rigotti, we are clearly in the presence of an individual automatic weapon, certainly, a precursor, but we are indeed in the “prehistory of gunsmithing” (an expression inspired by the work of Luc Guillou and Hervé Matous) which has never led to any adoption. The case of V.G. Fedorov’s 6.5×50 mm SR Arisaka automatic weapons is obviously a subject that deserves special attention. It is indeed an interesting work on the notion of reducing calibers compared to the caliber then in use in Imperial Russia / USSR: the 6.5×50 SR Arisaka being about 20 to 30% less powerful than the 7.62×54 mm R then in service. This allowed V.G. Fedorov to develop a “light” automatic weapon, especially in comparison with what was being done at the time. Clearly, the weapon was thought to be “somewhere between a rifle and a machine gun.” But perhaps not yet as “between the rifle and the light machine gun” as understood after the WWI: the work of V.G. Fedorov having begun in 1909! Keeping context in mind when talking about these topics is more than necessary. Similarly, there is no denying that the weapon was originally conceived as an individual weapon. But the fact that the fruit of this work is difficult to convince (in terms of reliability, but especially as far as we are concerned, on the effectiveness of its burst fire) and that it finally resulted in more conventional (and ultimately, abandoned) light machine guns for this period tends, in our opinion, to disavow its comparison with the category of “assault rifles”. Moreover, it is interesting to look at the place given to V.G. Fedorov’s automatic weapons by the Soviet historian specialized in weapons D.N. Bolotin in his work:

- In his book “Soviet Small Arms and Ammunition” (1995), they are placed in Chapter V “Machine Gun“, where they stand side by side with DP, RPD, PK and not in Chapter IV “Automatic rifles and Carbines” (the title of the chapter in Russian can be translated as “Automatic and semi-automatic rifles and carbines” »… probably an oversight in the translation). In this Chapter IV, only one weapon by V.G. Fedorov, a semi-automatic test model with a fixed magazine from 1925, stands side by side, among other things, with AVS-36, SVT-38 and 40 and SKS-45. But the fact that the book is not in the author’s native language (which is often a barrier in the transmission of ideas) led us to look at the Russian versions of the same work, two of which are available to us.

- In these Russian versions (1990 and 1995), V.G. Fedorov’s automatic weapons occupy a separate chapter: “Автомат Федорова и унификаця стрелкового оружия на его базе” which can be translated as “V.G. Federov’s automatic weapon and small arms unified on it”. In our opinion, this reflects the author’s thought: we are in the presence of very atypical works.

In all versions, none of V.G. Fedorov’s weapons are present in the chapter “Пистолеты-Пулеметы и Автоматы”, which can be translated as “Submachine-Guns and Assault Rifles”, which includes the Submachine Guns and what we call assault rifles. This is an opportunity for us to point out that the two concepts are distinct in the author as in Soviet tactical thought… and no, the Soviet “Avtomat” were not designed as “submachine guns”, but as a weapon replacing both the infantry rifle and the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More.

Thus, to try to include V.G. Fedorov’s automatic weapons in categories of weapons, which do not really share their conceptual philosophies, would undoubtedly be an error of thought introducing biases of interpretations. Finally, it is necessary to specify here that Vladimir Grigoryevich Fedorov can be considered one of the fathers of Soviet small-caliber armor thinking. This is not only due to his gunsmithing work, but also to his direct role in the development of the armaments industry, his mentorship of many designers and finally his publications on the subject.

To put some order on this caliber/ammunition issue, the table below allows you to get an objective idea of the energy proportions of a panel selected by yours truly, in particular those already in service at the time of the commissioning of the 7.92×33 mm. The latter serves as a “100” base for energy comparison with other calibers. We can thus see that the “weakest” cartridge (the 6.5×52 mm Carcano) of the representative panel of “ordinary” infantry calibers is already more than 30% higher than a 7.92×33 mm, which is considerable.

The data presented in this table comes from various sources: wherever possible, we have cross-checked it with serious sources. However, as always, the values are not measured directly by the author and are subject to caution. Obviously, we have chosen weapon / ammunition pairs allowing a ballistically rational exploitation for each caliber. Presenting the 6.5×50 mm Carcano fired in a 1938 carbine would have made little sense so long as the barrel reduction is castrating in terms of ballistic performance.

Regarding the innovative aspect of the 7.92×33 mm, it seems necessary to add here that, from our point of view, foreign research work that has never led to adoptions (or sometimes even to the slightest trial in troops) can only rarely be considered as “inspiring” factors for other nations… because their weapon designers simply never knew about it! We are thinking here in particular of the 8×35 mm Ribeyrolles, of which no one seems to have ever seen a copy in the 21st century! To carry out a parallel reflection with those mentioned for the work on semi-automatic rifles mentioned below, we are indeed in the presence of very interesting and avant-garde research, but ultimately marginal in terms of consequence. This does not detract from the merits of the people who participated in this work: some were certainly misunderstood visionaries… Nothing that results in human progress is achieved with unanimous consent. Those that are enlightened before the others are condemned to pursue that light in spite of the others.

We can also ask here the question of the .30 Carbine and the USM1. From our point of view, it is a weapon that echoes something that has existed and has been very specific to the United States since the beginning of the conquest of the West: the light carbine, which we refer to for ease as the “ranch carbine”. We made this informal semantic choice because it immediately echoes the specificities of rural America. These weapons were initially manual repeaters (such as Winchester 1866, then 1873 and 1892, Colt Lightning, Marlin 1894, etc.), then semi-automatic (Winchester 1907, Remington Model 8). These are weapons that are used “for everything”, but mainly in the civilian and rural context of the United States: defense, shooting pests and small game, training and even leisure, on foot or on horseback. Generally considered not powerful enough for “offensive” military use (although they would obviously be used in some conflicts), the calibers used could not claim to perform up to 300 or 400 m like an intermediate caliber. The very geometry of their bullets, generally more suited to subsonic than supersonic flight, testifies to a use thought to be at shorter ranges, such as for handguns (Pic.07). This type of weapon is also not very present (except for civilian stands) in Europe. Here is an opportunity to express ourselves on a theory encountered on social networks: could the 7.62×39 mm be the result of the meeting of the .30 Carbine and the 7.92×33 mm? The answer is obviously no and we are obliged to specify here that this is one of the stupidest theories we have read or heard… “Two things are infinite: The universe and human stupidity; and I’m not sure about the universe,”. Obviously, this apocrypha quote is attributed from Albert Einstein. How can anyone believe for half a second that the .30 Carbine can have any relation to the Soviet intermediate caliber? What diseased brain invents this kind of nonsense? All of them separate these calibers: the morphology of the case, the bullet, the ballistic performance and even the actual diameter of the projectile (Pic.08). On this last point, if the 7.92×33 mm, .30 Carbine and 7.62×39 mm have one thing in common, logistical, industrial, rational… it is to use the same diameter as the bullet as the caliber of the infantry rifle in service, namely: respectively: 7.92×57 mm IS, .30-06 Springflied and 7.62×54 mm R.

So, no, we have to consider the 7.92×33 mm as a major design innovation.

This consequent question of the caliber being studied, the two weapon’s organization are rather different:

- That of the FG 42 favours use in a lying position, although firing in the other positions is of course possible. In this respect, the weapon is not at odds with the infantry rifles of the first part of the twentieth century: they are perfectly suited to shooting in a prone position. It also has a specificity related to its “targeted users”: it is developed so as not to be hindered during “armed” parachuting. Thus, it is designed in such a way as to avoid impromptu snagging with all the equipment that surrounds the skydiver during his decent phase. The result is folding sights, a 10-round magazine (used during the jump to be immediately ready to fire once on the ground… Because, no, you don’t shoot during the descent phase of a parachute!) in the collective unit alongside 8 20-round magazines, a bipod, which, when folded, “smooths” the sides of the weapon and conceals the bayonet and an exaggeratedly inclined pistol grip on versions A to E. On this last point, it should be noted that in reality, this handle is only “a little more” inclined than the other German weapons, which often took up the grip of the P.08. But in the end, the grip of these early versions of the FG 42 was uncomfortable (especially when lying down), which explains its modification on the F and G types. As comrade Thomas of the “Le Feu Aux Poudres” YouTube channel rightly pointed out to us, the slope of the grip is actually very close to the half-pistol grip of the German Mauser 1898.

- On the STG 44 family, the positioning of such a prominent magazine downwards can be questionable: in absolute terms, it is barely usable from the prone position (as for the MP38 and MP40: the positioning on the side of the magazines for the number of SMGSubMachine Gun More and on the top for the number of LMG meets this unique requirement). Although it is sometimes presented as a “stable” point of support for shooting (including by period documents), we are highly doubtful: this practice seems to us to be proscribed from every point of view, as the benefits are doubtful and the problems associated with this type of practice are numerous. Rather, it would seem that here, shooting in a “standing” or “kneeling” position is favoured, which seems to induce use in phases of movement. But apart from this bulky magazine (which would probably contribute to the design of the 10-round magazine on the late works of the Germans), the organization of the weapon was rather “ordinary” for an individual automatic weapon, until then mainly represented by the category of submachine guns. Here, too, the weapon undoubtedly pays for its innovative value in “trial and error”.

At the end of this “catalogue” of the two weapons, it can be seen that from a conceptual point of view, and in particular because of its caliber, the STG 44 does not find any significant precedent. As for the FG 42, the situation is probably a little more nuanced.

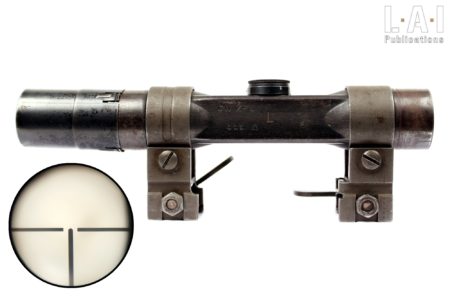

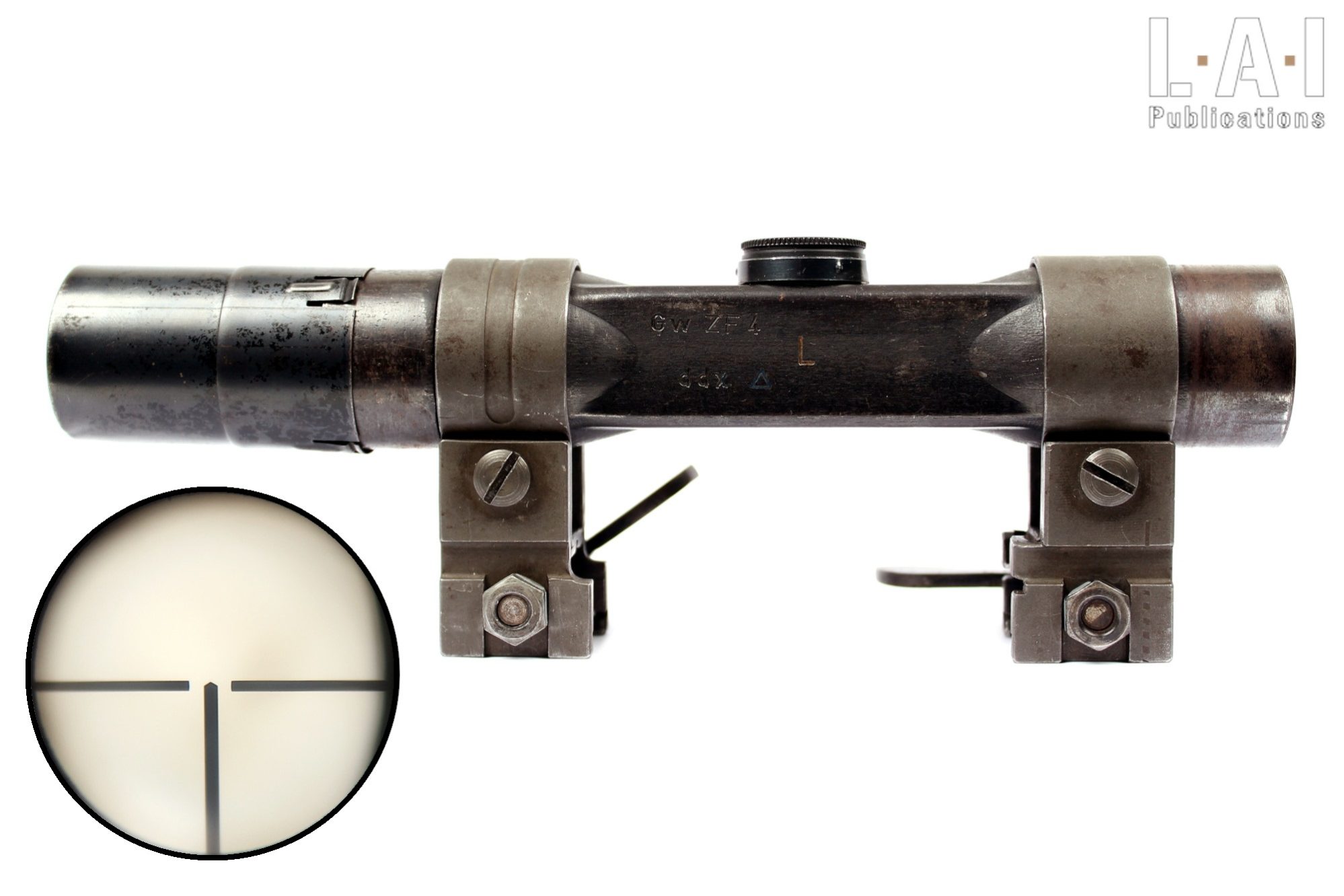

First of all, it should probably be reaffirmed here that the FG 42 is mainly intended to fire in single mode, and more occasionally, in bursts. The soldier is therefore equipped with 8 magazines of 20 rounds and a magazine of 10 rounds on the weapon at the time of the jump, i.e. 170 rounds… It’s not heavy in bursts. Especially since, as it is an individual weapon, the shooter is not resupplied by a “cohort” of suppliers as a collective weapon is (especially for paratrooper units). Similarly, the ability to mount a scope, which is required from the first expression of need, is also more in line with this: an increase in “firepower” as defined upstream (Pic.09).

If we look at individual weapons with selective firing mode using the caliber of the service rifle that was adopted before the FG 42, we find mainly (exclusively?) the AVS-36. The Soviet weapon was manufactured significantly until 1940: 65,800 examples according to D.N. Bolotin, far more than the 7000 FG 42s of any type manufactured before the end of the war. Others would also point to V.G. Fedorov’s automatic weapons. If the thing is not completely meaningless, we think, as already mentioned, that the weapon belongs to a conceptually “orphan” category. Therefore, the comparison seems misleading to us. On the other hand, if we ignore automatic fire, we find a large number of semi-automatic rifles in service caliber: RSC-17, G41 (W), Garand, SVT-38 and SVT-40 (and I may be forgetting some). The latter was derived during the war as an automatic weapon with the AVT-40, but the thing is anecdotal and the result, by the Soviets’ own admission, disappointing. In addition to all these weapons adopted before FG 42, a great deal of very advanced research (which will therefore be differentiated from more confidential work) has emerged all over the world. Generally speaking, the industrial world is “tending” towards semi-automatic rifle in “ordinary” calibers, in particular out of industrial and logistical pragmatism as already mentioned. So, certainly, in the case of the FG 42, the search for a truly exploitable automatic fire (and we will come back to this) marks a notable difference. But in reality, as controllable as it may be, the use of the burst that can be made of the weapon seems marginal to us. If the open bolt fire in burst mode protects the weapon from cook-off, the barrel remains frail for sustained fire. It should be remembered that with the rise in temperature of the barrel and its expansion, the weapon becomes subject to sub-cycle phenomena, and therefore to jamming. Added to the rather low and individual ammunition supply, the weapon is not very suitable for intensive support fire. But it corresponds to a “punch” use, no doubt as imagined (fantasized?) by or for the German paratroopers.

On the other hand, from our point of view, the “light” LMGs that became widespread around (and especially after) the WWI, some of which have a single or a slow-rate firing mode, are not comparable. However, they do show a reflection that goes in the same direction in terms of “firepower” as defined above. But we must look at these weapons for what they are: crew-served weapons that were never designed to replace infantry rifles. For comparison, the most interesting light machine gun here seems to be the LMG Johnson M1941. A little heavier (5.9 kg according to the English Wikipedia) and cumbersome because it was designed as an LMG that complements the semi-automatic rifle 1941 by the same inventor, it has always seemed strangely similar to the German weapon. We find the general arrangements (the magazine on the side, but further forward than the FG 42) and the specificity of the closed bolt firing in semi-automatic and open in burst. But as mentioned on the English Wikipedia, it can be assumed that when faced with similar problems, they adopted similar solutions (and let’s keep that thought very fair for everything else in this article). It is also totally implausible that Louis Stange had – at that time – knowledge of the work of Melvin Johnson… and vice versa.

The mechanical and production origins of the FG 42

Designed by Louis Stange for the Krieghoff firm, it is obvious that the FG 42 is a descendant of the general ergonomics of the MG 30 of the same designer. One of the major differences is the choice of operating system:

- The MG 30 operated on the principle of short barrel recoil with mobile rotary lock, the short barrel recoil being a highly prized system by the Germans until the early 1940s.

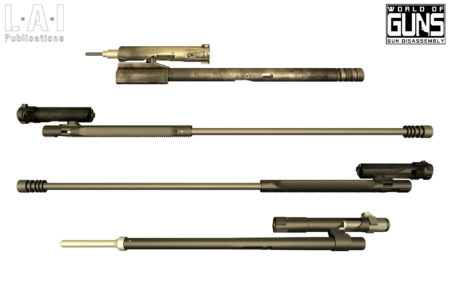

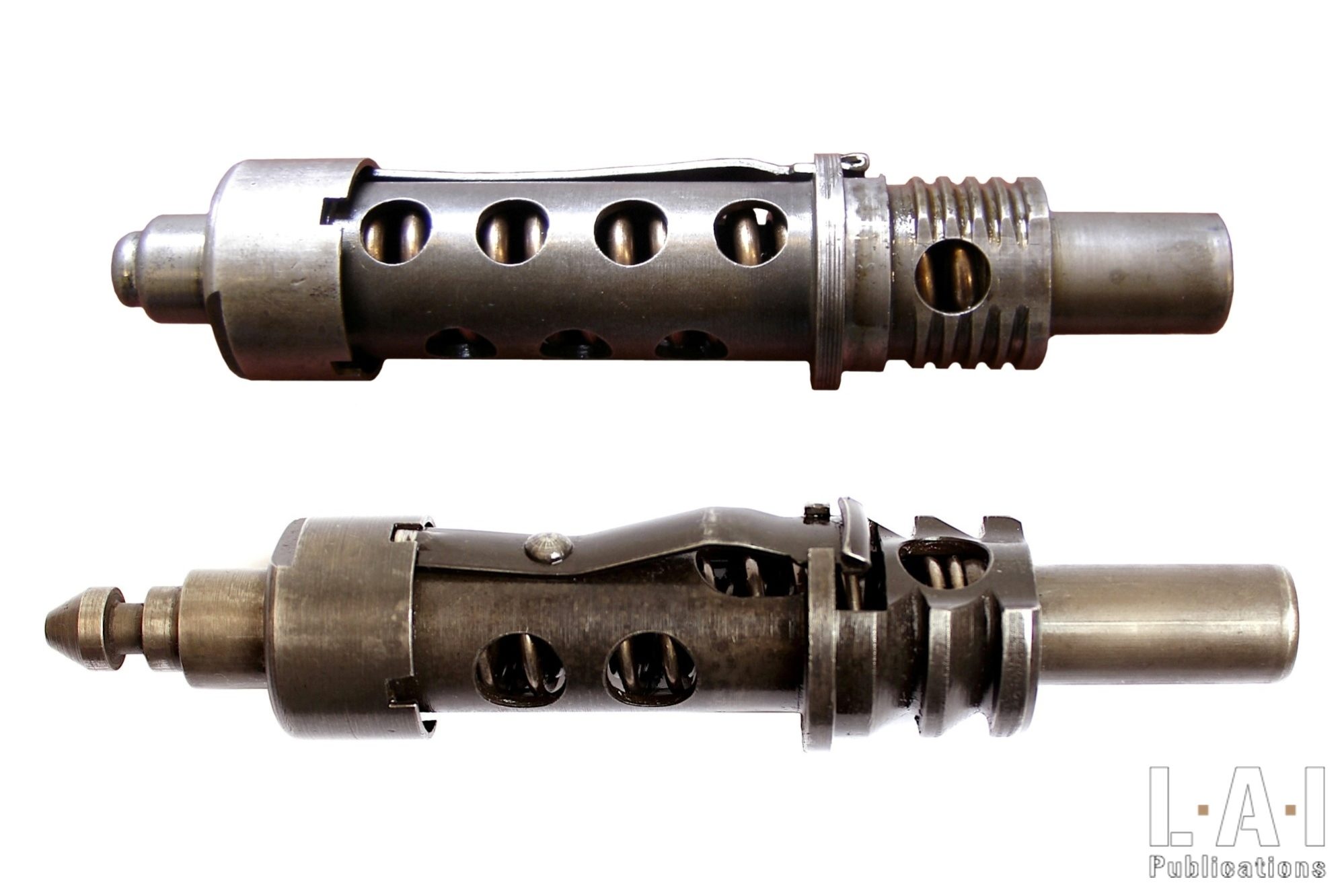

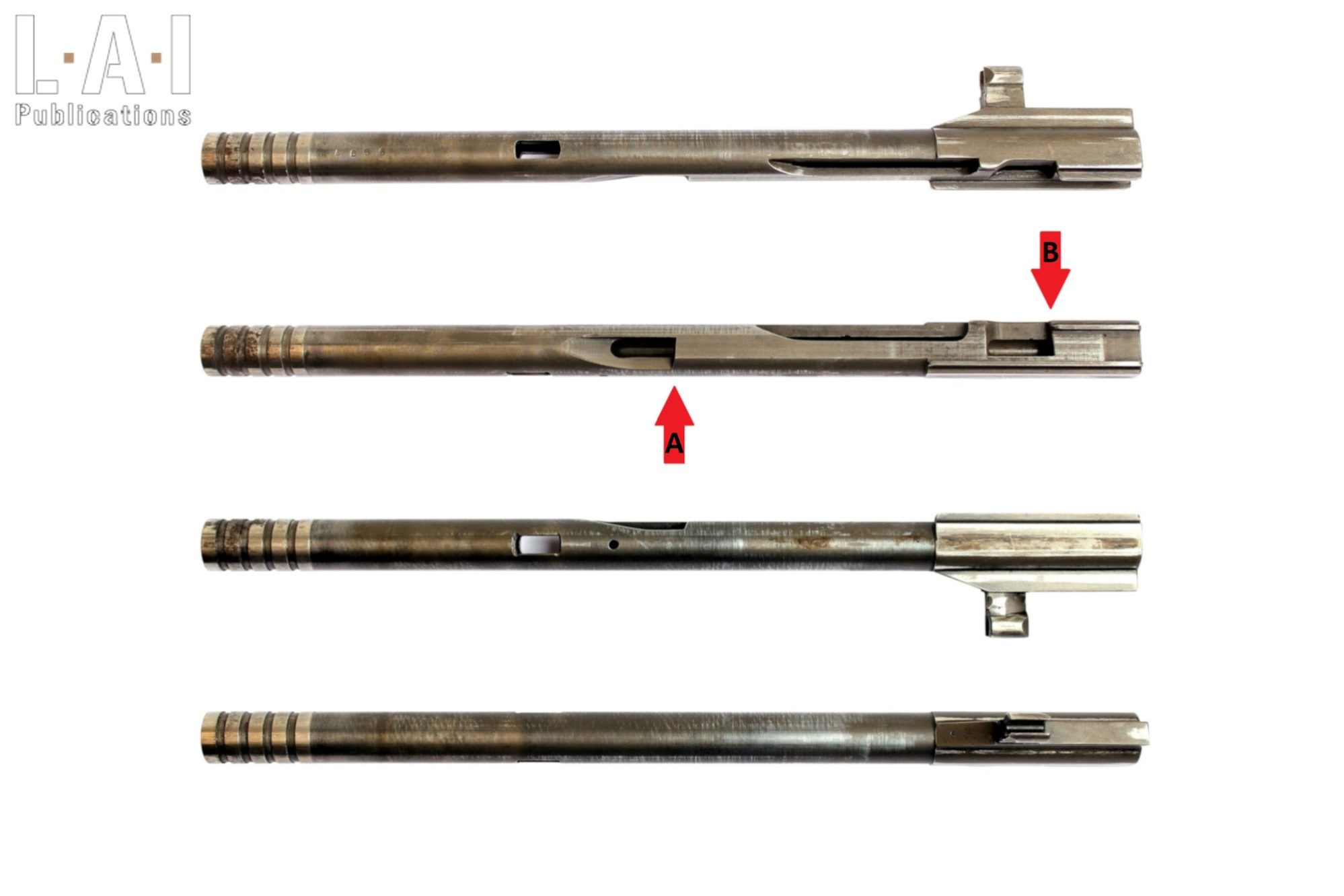

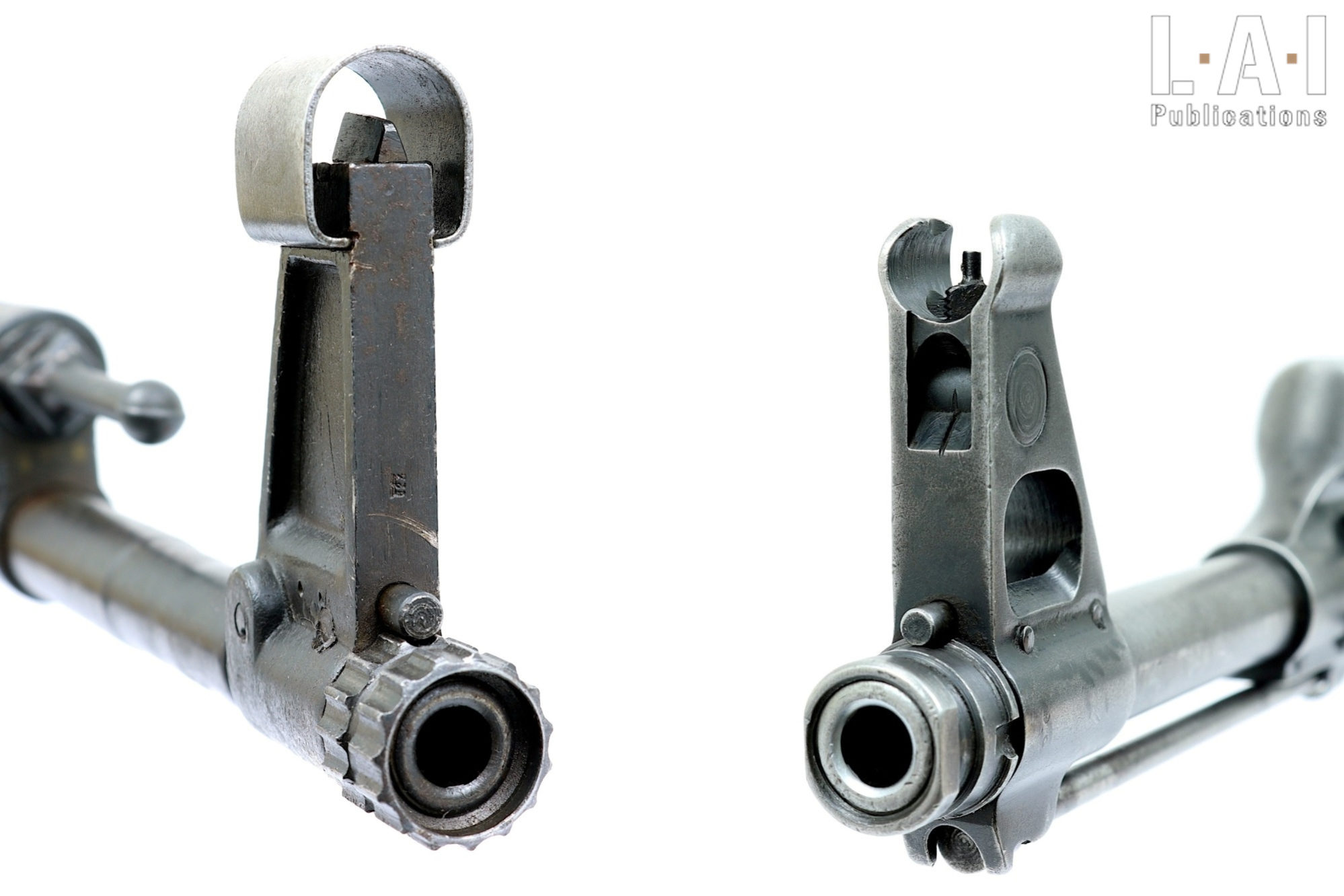

- The FG 42 is a gas-operated system with a piston linked to the bolt carrier with a rotary bolt which bear its lugs. As gas-operated systems are not very present in the German arms culture, L. Stange was inspired (let’s not talk about copying, but inspiration: things are often more subtle) from the British Lewis. If the Lewis has 4 lugs on the rear part of its bolt, Stange will have 2 on the head of the bolt on his FG 42 (Pic.10). In both cases, there is no primary extraction… Too bad for rotary locks!

It should be noted here that the Lewis is a weapon that left a strong (and positive) mark on the Germans during the WWI: it was a type of weapon that was almost non-existent in the German arsenal. The water-cooled MG08/15 is ergonomically unresponsive to rapid deployment and implementation, and can hardly compete in terms of maneuverability on the battlefield.

The placement of the magazine well, on the left side and at the handle level (which makes it a “semi-bulpup“, therefore a quite compact weapon despite a 50 cm barrel), is a legacy of the MG 30. In the end, the “silhouette” of the FG 42 is close to the MG 30. However, we note that the alignment of the barrel is a little less focused on the “middle” of the stock on the FG 42: it is slightly above. But the result is ultimately similar and this allows you to keep a line of sight close to the barrel. It can therefore be considered a good compromise. We find one borrowing from the BREN (the same one that had “scolded” the Fallschirmjäger in Cretes): that of allowing the receiver/barrel assembly to buffer into the stock (Pic.11). This makes it possible to “transform” the recoil: de facto, it breaks its dry and violent aspect by breaking it down into a more continuous thrust that is better apprehended by the human body… including the brain. The use of a muzzle brake (this is the real function of the muzzle device of the weapon, sometimes misrepresented as a flash hider) is not really innovative, but rare enough to pay particular attention to it (Pic.12). The concept has been known for a long time and is already used, for example, on the AVS-36 where the muzzle brake and climbing compensation functions are carried out by a single device.

By the three provisions mentioned above: barrel alignment, buffer in the stock and muzzle brake, we can see that there has been real research here to improve the behavior of the weapon when firing. It should be remembered here that this improvement does not only impact burst firing, but also both firing modes: a lower de-pointing of the weapon in single shot allows an acceleration of the repetitiveness of the action. And thus, an increase in “firepower”. The FG 42 really stands out for its exceptional shooting skills for a 5 kg weapon in such a powerful caliber. Having had the privilege of firing (in both semi and automatic mode) the FG 42 Type E and G (original!), we note that the climbing of the weapons remains low. It may be noted here that when shooting from a prone position, the middle position of the Type E’s bipod poses a major problem in our opinion in its integration. While this arrangement is much better for tracking moving targets and for distributing the weight of the weapon, on automatic fire it tends to tilt the weapon, and even worse in the case of the Type E, to close the bipod. The thing will be modified on the Type F and G by repositioning the bipod and consequently its closing direction.

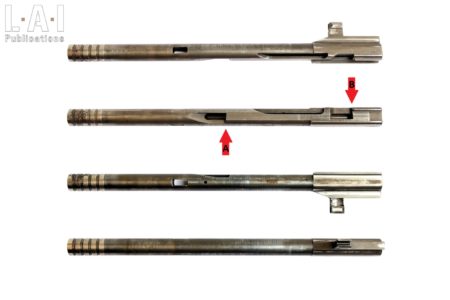

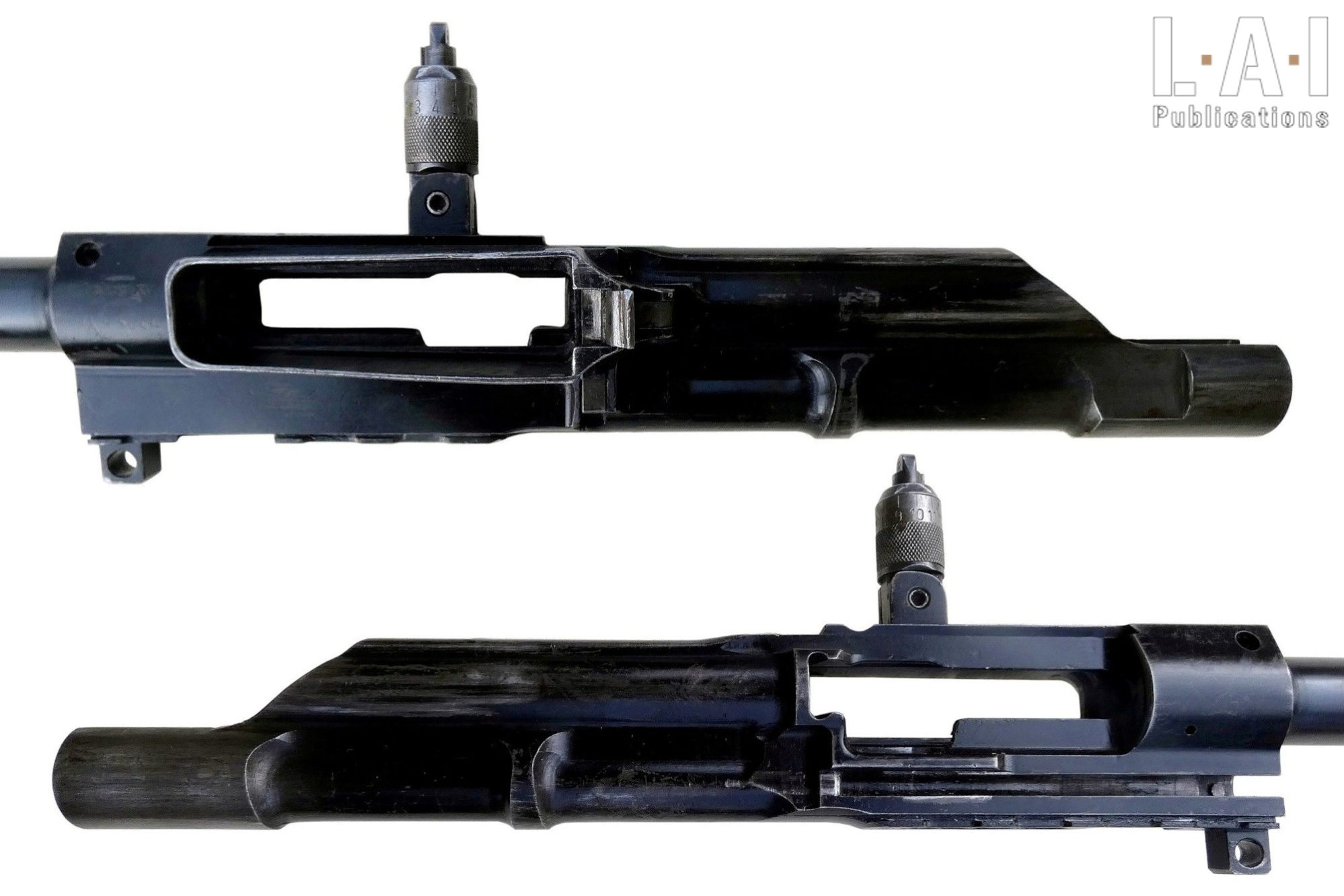

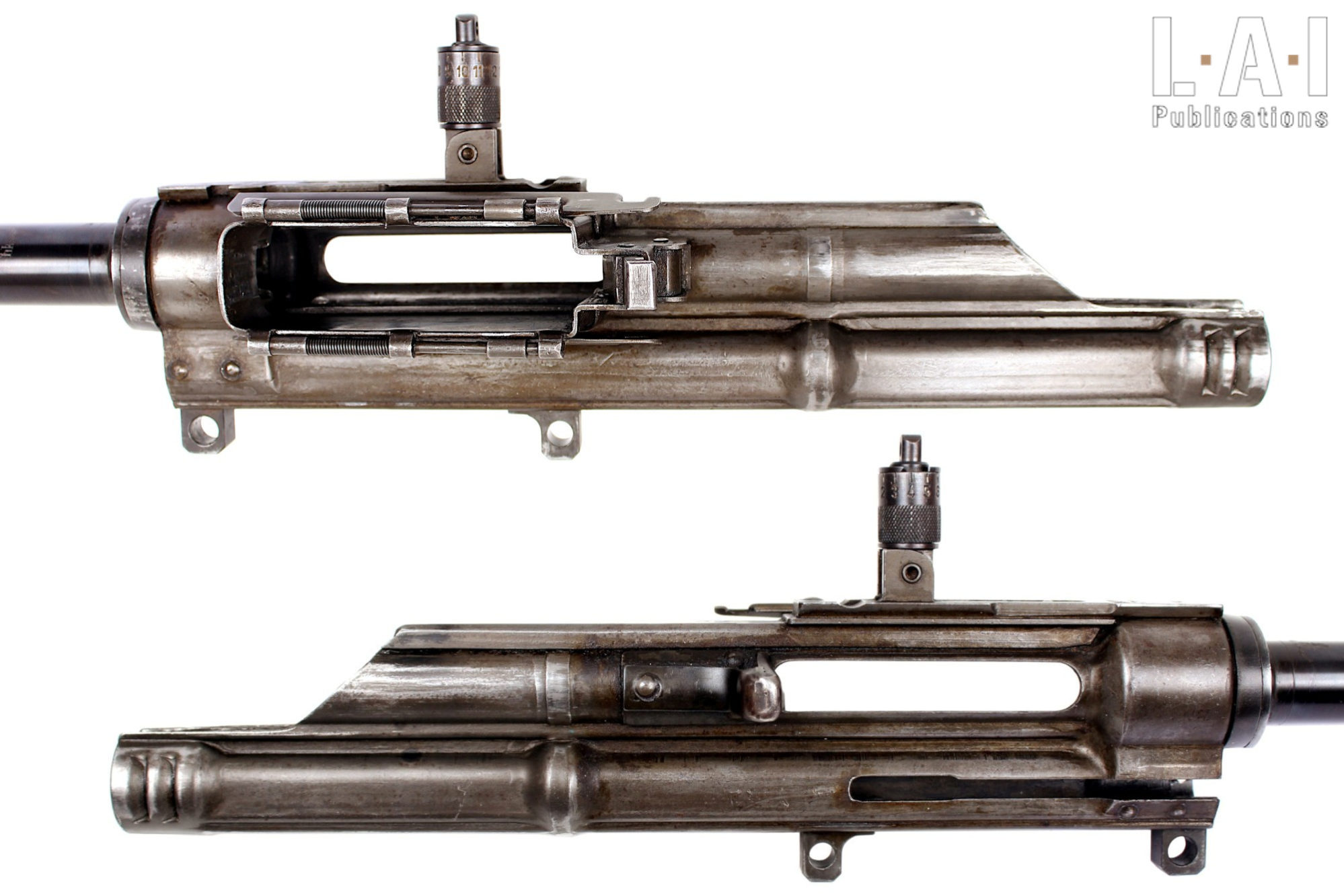

From a production point of view, the FG 42 is marked by the introduction of stamped sheet metal:

- The thing is “minor” at first. On the Type C, D and E: there are in particular (but not only) massive parts such as the stock, the grip and the bipod. (Pic.13).

- The thing is “major” in a second step. With the Type F and G, in addition to the parts mentioned above (except for the stock, which is made of steel reinforced laminated wood), it is indeed the receiver that is made of stamped sheet metal (Pic.14). With a machined locking nut, of course!

The introduction of a stamped sheet metal receiver is a real tour de force, especially for an individual weapon using such a powerful ammunition. It is probably the result of the same designer as the MG42 frame, Dr. Werner Gruner (called Dr. Grunow in some sources, but he is the same person), of the firm Grossfuss. That being said, it’s the same person, but with quite different results. And for good reason, the dimensional prerequisites have nothing to do with each other. For small-arms, we have here one of the rather pioneering uses of stamped sheet metal in such complex shapes.

It should be noted, however, that at the same time, other works made use of it and led to the adoption of weapons before the end of the war:

- In Germany: with the MP40, MG42 and STG 44, each time with quite different uses of stamped sheet metal.

- In Russia: with PPSh-41 and PPS-43.

- In England: we could mention here the case of STEN Mk.III. Unlike other STEN variants, its receiver is constructed from a wrapped sheet of metal that is welded at its top. The receivers of the other variants of STEN are made from a steel tube, the production of which (potentially by various different processes) is ultimately quite different from the stamped sheet process, even if the latter has obvious industrial advantages compared to machining a raw (forged or not) metal part.

- In the United States, towards the end of the war with the M3, not to mention the “Liberator” single-shot pistol.

It should be noted that the work outside Germany concerns almost (because of the Liberator) only submachine guns, i.e. weapons using ammunition of a rather low power. An important difference.

Our comrade Pierre Breuvart rightly reminds us in a conversation around these themes that the reflection around the simplification of production by uses other than the use of forged / machined parts was already explored in France during the WWI. Indeed, weapons such as the CSRG 1915 “Chauchat” are already exploring production uses aimed at reducing costs and speeding up production rates. However, it is not yet stamped sheet metal.

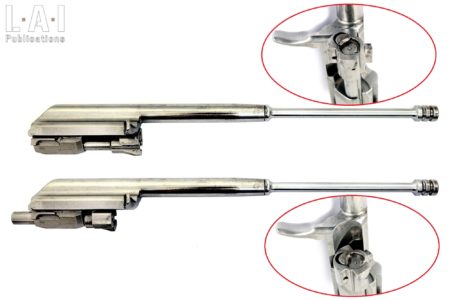

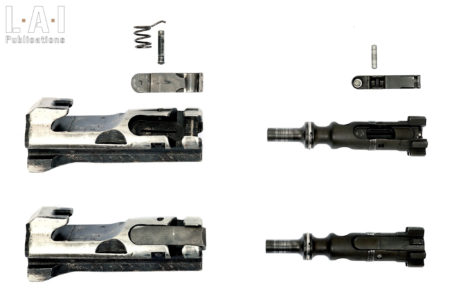

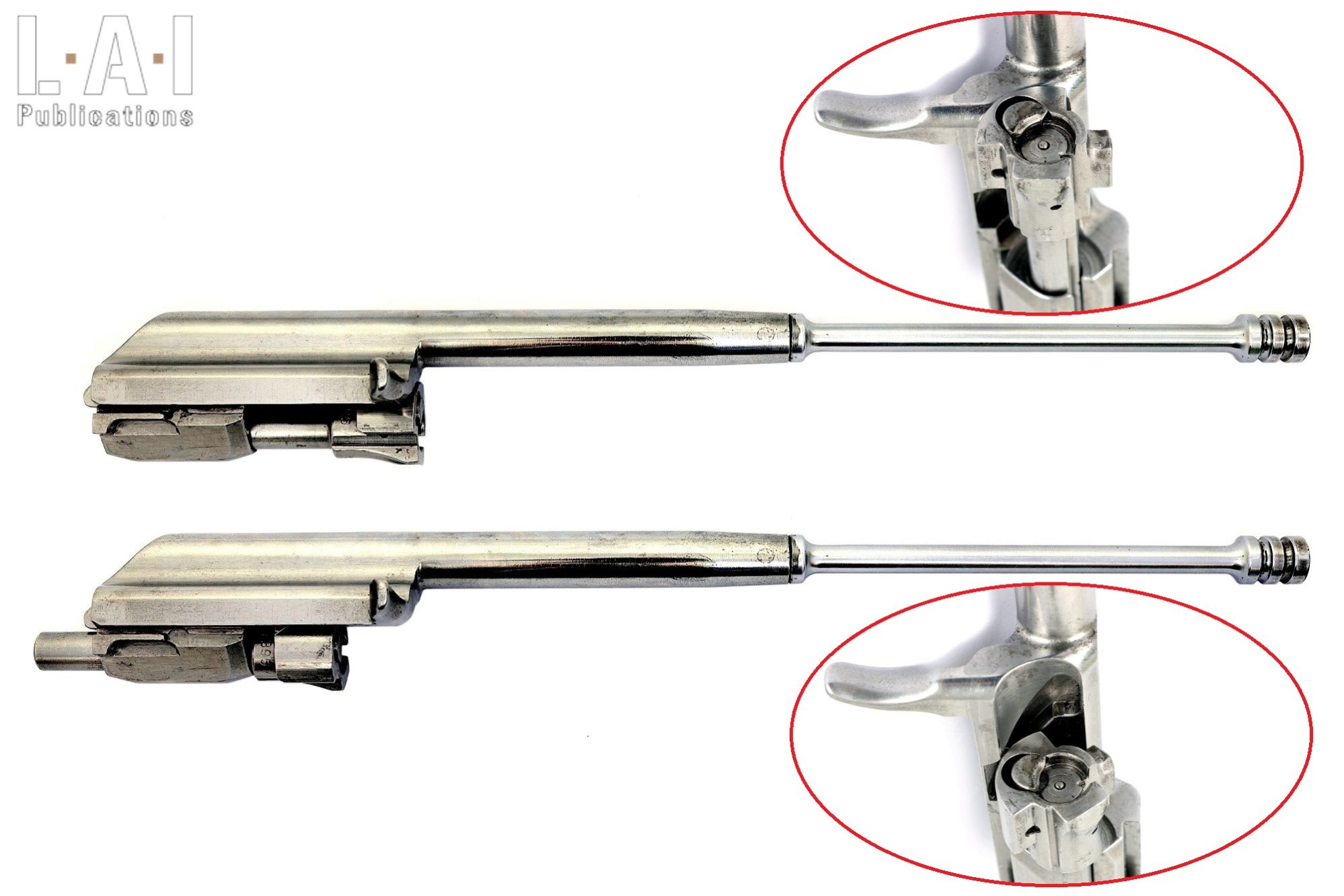

Among the interesting innovations (we know of no predecessor on this point), we can distinguish the way in which the single mode was incorporated, with great simplicity, on a mechanism originally designed to fire in automatic only and from an open bolt. In the case of the FG 42, there are two “lateralized” cocking notches on the bolt carrier, widely spaced along its length (Pic. 15). Thus, by positioning the selector in the “semi-automatic” or “automatic” positions, we switch the sear to one side:

- In semi-automatic, the sear is tilted to the left, hooks onto a bolt carrier notch located at the rear of it while being subject to a separator controlled by the rear movement of the bolt carrier. It thus creates closed bolt firing (by the location of the cocking notch at the rear) and the semi-automatic function (by the separation thus induced).

- In automatic mode, the sear is tilted to the right, hooking onto a bolt carrier notch located at the front of it while shunting the separator. It thus creates: open bolt firing (by the location of the cocking notch at the front) and the automatic function (by absence of separation during firing).

More anecdotally, we can finally mention that the bayonet of the FG 42 is inspired by that of the MAS 36 and the shoulder strap is that of the Gewehr 1898.

The mechanical and production origins of the STG 44

Beyond the conceptual aspect of the STG 44 family, which is extremely linked to its caliber, the mechanical inspirations are… Nothing too exceptional! These include:

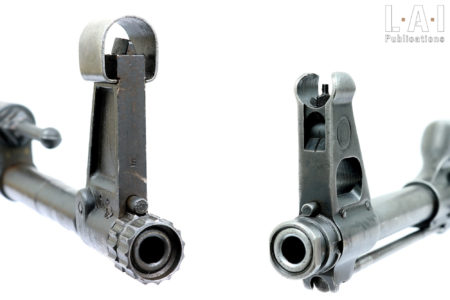

- The gas-operated system using a linked piston to the bolt carrier acting on a tilting bolt via an inclined plane is present in many foreign machine guns. In the case of the STG 44 family, the inspiration came directly (and openly) from the work of the Czech Václav Holek, which led to the ZB-26, ZB-30, etc. and thus to the British BREN (Pic.16). In the case of the STG 44 family, the feeding is achieved from the bottom, the piston is upwards and the locking recess is downwards (it usually goes together…).

- The large-diameter spiral recoil spring that fits into the stock is the spiritual heritage of the German MGs, and in particular the MG 30 and MG 34.

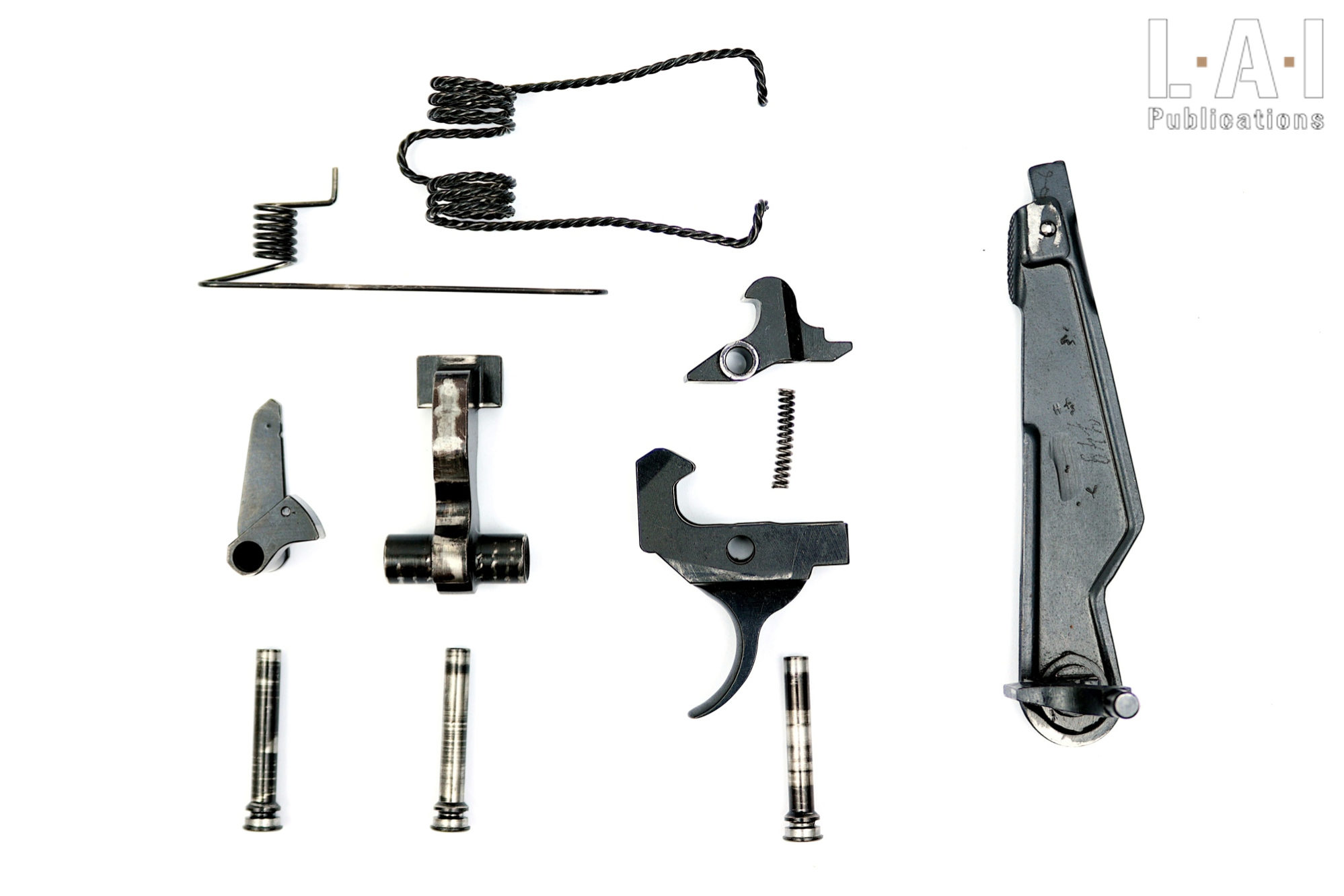

- The firing system, a bit too complicated for the functions it allows, is never more than an umpteenth rehash of the firing by a circular hammer, with a crested notch for the sears: we have been finding this on John Mose Browning’s systems since the beginning of the century. It should be noted that its complexity (number of parts) is probably linked to a desire for “production simplification” (by using many parts rather simple to produce)… but which, in our opinion, has clearly “gone wrong” (Pic.17)! On the progeny of the weapon (CETME and HK G3, we will come back to this later), the thing will be redesigned in depth for a much more convincing result and by freeing itself from the “Brownian” inspiration. Generally speaking, before the WWII, as with the use of gas, the Germans did not have a real culture of firing by circular hammers, especially on long guns: striker systems were predominant.

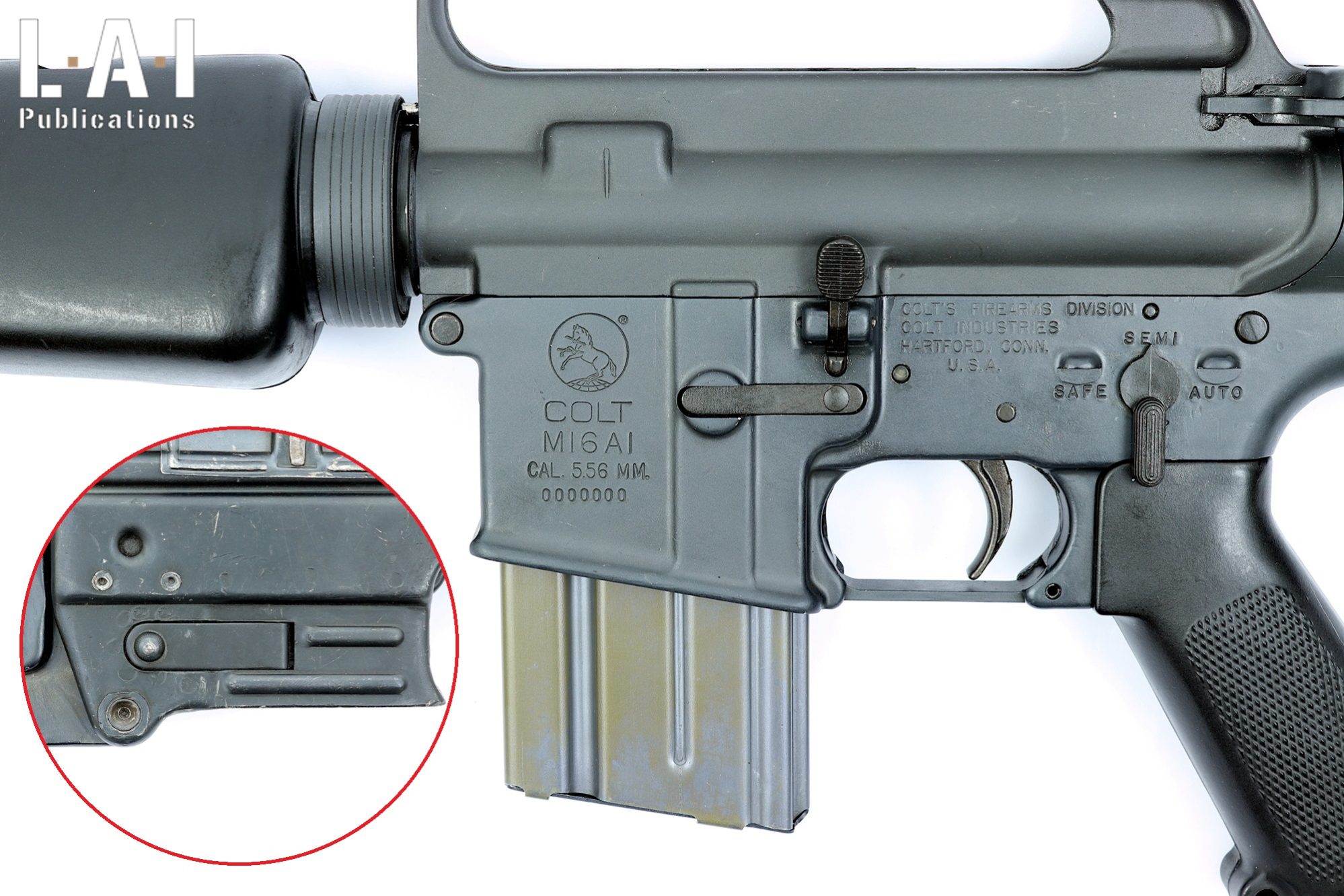

- The magazine well and its knob are clearly derived from those of the MP-38 and MP-40. The magazine is inserted straight into the magazine well and not head-to-toe (unlike the FG 42 – Pic.18).

- The organization of the safety and fire selector into two separate controls can be found on various weapons, including the Thompson SMGs (Pic.19). This is also one of the evolutions of the transition from the FG 42 from type E to F (then G): one senses that it is not a “coincidence”, but a well-thought-out act (Pics.20 and 21). In the case of weapons from the STG 44 family, the rather surprising thing is to have made the choice to position the firing mode selector on a transverse push button which is reminiscent of the safety of the MG 42! For instruction, one could have dreamed of something more uniform. But it is important to remember that at the time of the design of the first weapons of the STG 44 family, the MG42 was not yet part of the gunsmithing landscape. On the other hand, from an ergonomic point of view, this choice is obviously more practical: safety is implemented with great ease while changing firing modes requires special attention. Of course, the safety took over the “standards” of the P.08 and the MG34.

On the production side, it’s the same as for the FG 42 (F & G) and MG42: we’re at the forefront. It is a pioneering use of stamped sheet metal for the manufacture of frames for weapons requiring locking. We will detail it later in this same work for comparative purposes.

For all these weapons, it can be stressed that the use of sheet metal is not the only innovative aspect: faced with the lack of supply of quality steel, the Germans resorted to nitriding, which stiffens the metal on the surface. Similarly, the prerequisites in terms of bearable stress and barrel longevity will allow the emergence of the first cold-hammered barrels for the MG42 and G43. In addition, this process will be particularly suitable for mass production. However, it is not known here whether the barrels of the FG 42 and STG 44 benefited from this process. This is likely for the STG 44, but probably less so for the FG 42 (the weapon did not really go beyond the pre-production stage).

Conceptual legacies

From a conceptual point of view, while some people think that the FG 42 prefigures the “Battle Rifle” of the Cold War, for our part, we would be more nuanced. In our opinion, and as already outlined, it was the set of semi-automatic rifles and the few select-fire rifles produced until 1945 that prefigured the “Battle Rifle” of the Cold War. Indeed, from a purely practical point of view, the automatic mode of these weapons is not usable: it is at best a conceptual error (which often becomes ephemeral) or at worst a mercantile “scam” (look, my rifle is automatic!). But it should be noted that in the case of the FG 42 the burst seems much more exploitable than on a G3 or a FAL (or a Zastava M77, etc.). And we speak from experience: we had the privilege of trying the FG 42 types E and G, in single and burst shots, as well as several “Battle Rifles”, and in particular, the FAL and G3 on many occasions (but never the M14 in burst… Maybe one day?).

Be careful, more usable does not mean that it is a panacea: for my part, the FG 42 is, like the MKb42(H), a conceptual error. This is not a criticism but an observation: these mistakes are necessary, but we should not attribute to them the merits of a concept that has finally “hit the nail on the head” on the entire formula. After the war, the FG 42 certainly inspired certain weapons on precise points of detail, but in the end none of the weapons adopted took up “the formula as thought”. Thus, with weapons such as V.G. Fedorov’s automatics or the USM1, they look a bit like conceptual orphans (weapons that have taken over the .30 Carbines exist, but these are objectively marginal on a global scale).

It should be noted here that some (conceptual) comparisons seem to us to be qualified.

Concerning the experimental British EM-1 (Korsac), EM-1 (Thorpe) and EM-2 (Janson) rifles: from a conceptual point of view, the weapons do indeed take up part of the specifications of the German weapon, but in a “real” bullpup. But let’s remember that this is simply the “individual automatic weapon with compact selective fire”. In our opinion, what leads us to compare this “series” of weapons are the direct borrowings made by Korsac’s EM-1 from the FG 42 and which are undeniable. On the other hand, when you compare it with the EM-1 (Thorpe) and EM-2 (Janson), the similarities end up being in the order of “that has 4 wheels, so it’s a Ford T”. Once again, it should be noted here that these weapons will not be put into production or descended (the British SA 80 only shares the concept of bullpup).

While the Swiss STG57 is in some ways evocative, the weapons are ultimately different in too many ways. Yes, some prototypes made in Bern bear a strong resemblance to an FG 42 but:

- These never went beyond the so-called prototype stage.

- These use an intermediate caliber.

As far as the M60 is concerned, the bolt carrier group is certainly extremely close. However, the M60 is very clearly a machine gun (therefore, a crew-served weaponA weapon which is designed to be used by a team of several p... More dedicated to support firing) and not a selective-fire individual rifle. So, conceptually, weapons have absolutely nothing to do with each other. So yes, there are works (notably the experimental FM T-44) that have consisted of modifying FG 42s to feed them by band using feeding tray from the MG 42, but should these be considered as the direct ancestor and as the only source of inspiration for a weapon that is ultimately very different from an FG 42?

It seems necessary to recall at this stage of our work that the relentlessness in the FG 42 project, of a concept probably already identified by some as not very rational, at the time of its development, seems to have been largely influenced by H. Göring’s direct (financial) interest in the Krieghoff firm and by the fact that Hitler did not want to see the 7.92×57 mm IS dethroned by a less powerful caliber. Two considerations that went against the pragmatism of Louis Stange, who would have seen his weapon in 7.92×33 mm according to some sources.

As for the STG 44 family, the MP43/1 (the first version to come close to the version finally adopted by the Wehrmacht) holds the fatherhood of the “assault rifle” concept. Why specify the “MP43/1” and not the MKb42(H) here? For the simple reason that the use of open bolt firing (in single as well as in automatic firing) on an individual weapon to engage at “intermediate” distances (i.e. around 300-400 m), is objectively a technical error. This leads to a loss of accuracy in fine due to the unbalance of the weapon when firing. Moreover, the thing will be corrected by the Germans themselves, including on late versions of the MKb42(H). Thus, the MKb42(H) is, in our opinion, a “failed prototype assault rifle”, and the MP-43/1, the first “assault rifle” (the MP43/2 being, to our knowledge, another version firing with an open bolt). It may be recalled here that we are not a fan of the term “assault rifle”, which we find ill-suited to describe the weapons in question. This is discussed in detail in our article “The choice of words: reflection on the semantics of the categorization of firearms”: this work seems fundamental to us, because it militates for the emancipation of ready-to-think.

We could qualify the matter by specifying that it is the first to “cross the finish line” with the adoption of the MP43, MP44 and STG 44… But still, 6 years (and that’s a lot in this context) before the first AK-47 Type 1 productions (1949). So, this is the first “hands down”. Because once again, this is what is interesting from a practical point of view: “when the concept comes into use and is a milestone from a global point of view“. Otherwise, it remains a “technological demonstrator”, whose design offices are filled…

He thus won the paternity of the first intermediate-caliber weapon and of the weapon described as an “assault rifle” that was actually adopted. And by the way, it will give the baptismal name to the category. So it will have a considerable legacy that still fills the arsenals of all the armies of the world to this day!

In the end, what is quite ironic is that the FG 42, through its promoters in the “highest” of Nazi Germany, was destined to become the “standard” weapon of the German army after the war. Ironically, this will not be the case, and in fact, it will never be the case from a pure conceptual point of view. No, it is the concept carried by the STG 44 family that will have this honor until today! And yet, the concept struggled to find a clearly defined place in the German army during the war: refused by Hitler on 3 occasions, it ended up constituting (up to some sources) 1/3 of the infantry individual small arms in 1944… for having been produced in the end at more than 400,000 units (all variants combined: we are in the same order of the number of FAMAS F1s manufactured!) while the FG 42 will struggle to exceed 7000 units.

Mechanical and production legacies

In the end, the mechanical legacies of the FG 42 are few and far between, probably because its formula itself will not be used. There are occasional similarities on some weapons: the muzzle brakes of the ZFK-55 and early AR-10, the sights of the STG-57, bolt carrier group and the buffer on the M60. The most borrowed weapon is undeniably Korsac’s British EM-1 experimental rifle… so a weapon that will never be put into service.

We can emphasize here that it does not seem to us to be an aberration of thought here that it is indeed the FG 42 that will introduce the use of the rotary-adjustable rear sight which will be redesigned and simplified on the G3 and its descendants. Similarly, it is likely that the weapon is somewhat inspired by Eugene Stoner for the design of the AR-10… but an inspiration among many others (and this is not a criticism, quite the contrary!). It should not be forgotten that in the shadow of Eugene Stoner is Melvin Johnson, a consultant at Armalite at the time of the design of the AR-10 and whose work before 1945 clearly testifies to a reflection in some respects very similar to that carried out by the Germans for the FG 42 as mentioned above.

On the STG 44 side, we’re going to have to spill a lot of ink (in fact, used a lot of bits). So, let’s try to definitively debunk a myth here: the STG 44 does not have the mechanical or production paternity of the M.T. Kalashnikov assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More. And we’re going to go into more detail here to make it clear that this is not an ideological opinion, but a technical analysis. Because this is the “trial” that is usually made when this subject is broached… usually by people who are themselves inhabited by partisan beliefs and ideology. However, here, we are only talking about “scrap metal”…

Before we talk about the weapons themselves, let’s take a look at the calibers, which, as we mentioned, is the major innovation of the STG 44. History will remember that the Soviet intermediate calibers 7.62×41 mm (prototype version, adopted in 1943) and 7.62×39 mm (final version, adopted in 1945) were the result of the work directed by Nicolai M. Elizarov and Boris. V. Semin. The transition from the prototype version to the final version is said to be due to difficulties encountered (in particular as regards the holding of the bullet in the case) during the development of the weapons of M.T. Kalashnikov and S.G. Simonov. Anecdotally, the development of the 7.92×33 mm calibers was also influenced by H. Schmeisser: we owe him the reduction of the taper of the case, because he complained about the curvature of the magazine.

The same controversy surrounds the Soviet caliber as there is around M.T. Kalashnikov’s weapon: this invention is not Soviet, but German. If we will see that for the weapon, the thing can be easily contradicted by an objective technical argument, for the caliber, things are a little more complicated… because nothing looks more like a ammunition than any other ammunition! And yet, appearances are, as is often the case, deceiving.

The fact is that it is true that the “prototype” version of the Soviet intermediate caliber, the 7.62×41 mm adopted in 1943, is very similar to the 7.75×40.5 mm from GECO developed during the 1930s. As a result, it seems legitimate to question the fact that the Russians were inspired by the GECO cartridge for their work. For his part, the French author Philippe Regenstreif, a specialist in Soviet small-caliber ammunition, specifies in his book “Russian Military Ammunition for Small Arms 1868 – 2008“:

“We insist on the fact that it is ridiculous to talk about a possible filiation of the 7.62 mm M43 from the German 7.92×33 (or Kurzpatrone) or any other comparable cartridge! “.

From his point of view, there is a chronological problem in the version of events put forward by analysts defending this hypothesis. And indeed, we can only agree with him: this hypothesis is based on the fact that the Soviets discovered the 7.75×40.5 mm caliber when they entered Germany in 1945. However:

- On the one hand, not only was the 7.62×41 mm caliber adopted in 1943, but weapons dating back to 1944 are known for this caliber.

- On the other hand, 1945 was precisely the year when the 7.62×39 mm replaced the 7.62×41 mm of 1943. And let’s make it clear that the 7.62×39 mm is not a “slightly modified” 7.62×41 mm, but in fact a rather deep redesign of the case and bullet design.

The hypothesis of a Soviet “copy” therefore seems to us implausible on this basis.

However, to our knowledge, two hypotheses are quite never mentioned on this subject:

- That of industrial exchanges and military cooperation between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that existed before the war (the war between Germany and the USSR began on June 22, 1941, not September 1, 1939).

- That of espionage.

Admittedly, neither of the two hypotheses is documented in the present case: but should we exclude them from our reflection and from the field of “possibilities” for all that?

With regard to industrial exchanges and military cooperation, it is known that the extension of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact to economic agreements will affect the military field. And this has given rise to technological transfers that are much more sensitive than small-caliber armaments, such as aviation, artillery, and the navy. Because, yes, we have to be lucid about our passion: the individual infantry weapon has only a very small weight from a strategic point of view in a major conflict such as the WWII (which partly explains the disenchantment of many leaders from different backgrounds for the specialty). Therefore, how can we completely exclude the fact that Soviet specialists did not hear of German work on caliber reduction (a subject which, as a reminder, had been questioned in Russia/USSR since 1909…) before the beginning of the war? While the official delivery of the prototype is probably to be ruled out, there is another reason why the characteristics of this caliber have been leaked. If only through the verbal exchanges between two individuals who are passionate about their work during an official or unofficial visit… It’s a real experience! In these moments, ideological barriers tend to collapse, because sharing a common passion usually brings people closer together than deadly ideologies separate… Yes, it’s still a real deal! We then find ourselves sympathizing with people whom our ideology disapproves of…

When it comes to espionage, let’s keep in mind that the most successful espionage operations are the ones no one ever hears about! Some will accuse me of veering into conspiracy theories, to which I will accuse them of naivety. To believe that states (all of them, whatever their political systems) do not engage in clandestine activities and that these are often (always?) hidden from the public (and forever!) is, in our opinion, a profound misunderstanding of human nature and the history of humanity… and has been since the dawn of time! It should be remembered that the Soviets had easier access to the atomic bomb through “leaks” that came directly from Los Alamos… Moreover, it is quite likely that the Soviets took advantage of the German means of production after their captures! Failure to do so would be a strategic mistake.

Despite all this, it is necessary to understand here that in the end, the 7.62×39 mm actually adopted is put into service and technically very different from the 7.75×40.5… and even more than 7.92×33 mm. Compared to the latter, the body of the 7.62×39 mm case is much more conical, and “compensates” (in the search for performance) this loss of volume of the powder chamber by an elongation of the case. The result is a deeper, more curved magazine… and more able to shoot from a prone position. It should be noted that a more conical body facilitates the feeding and especially extraction phases (the removal of the case from the walls of the chamber is easier). Architecturally, the bullet of the 7.92×33 mm is made of a sintered iron core, coated with lead, all lined with tombac plated steel : that of the 7.62×39 mm M43 “PS”, the ordinary bullet originally adopted, is a stamped mild steel core, coated with lead, lined with tombac plated steel. We therefore find the same desire to save lead and copper on both sides (a desire that predates the birth of intermediate calibers), but with very different technologies and terminal ballistic performance no doubt as a result. Sintered iron and stamped mild-steel are two very different things.

With the thorny problem of caliber mentioned, we will begin the comparison of German and Soviet weapons with one of the least emphasized aspects in this field, and yet one of the most revealing: the way in which these weapons are manufactured.

For the production of the stamped sheet metal frame of the STG 44 family, Hugo Schmeisser had recourse to the know-how of the Merz-Werke firm: because Schmeisser himself was not a specialist in the subject at all. Although Hugo Schmeisser, father of the STG 44, was made a “stay” by Russia, in Izhevsk, from the end of the war until 1952, it is obvious that the work of the German stamped sheet metal will pass through France (CEAM, Mulhouse), then through Spain (CETME, Santa Barbara), to return to Germany with the help of Holland (Pics.22). All this eventually gave birth to the G3 / HK-33 / MP-5 weapons family, from the firm Heckler & Koch, itself made up of former Mauser employees. It should be noted that while Hugo Schmeisser was in Suhl at the end of the war, an area occupied by the Soviets after the war, the Merz-Werke company was based in Frankfurt, an area occupied by the Americans. Thus, the specialists of this factory, authors of the case of the weapons of the STG 44 family (whose names we have not found) may have succeeded in an exile in a country… more welcoming! Maybe they accompanied a certain Ludwig Vorgrimler (father of the CEAM-50 and CETME)… who, as we know, was not alone in his “exile” through France and Spain. But they may have simply stayed in Germany, to make typewriters and office furniture, which was initially their core business.

As mentioned earlier, the Soviets had not waited for the Germans to make stamped sheet metal. And in the context of the beginning of M.T. Kalashnikov’s work on his “Avtomat” (1944), it is quite natural that the manufacturing method is previously selected. Thus, M.T. Kalashnikov’s weapon clearly finds its production inspiration in Soviet weapons, and probably in the work of A.I. Sudayev (designer of the PPS-42 and 43 but also of an Avtomat prototype: the AS-44). It is also known that M.T. Kalashnikov received help from many actors of Soviet industry, including A.I. Sudayev, whose office M.T. Kalashnikov shared (he “squatted” it in his own words) at the Shurovo polygon. As such, M.T. Kalashnikov never claimed to be “a solitary designer,” but rather to have been at the helm of a team throughout his career. One thing should probably be clarified here: the job of the weapon designer is generally not to master all the areas necessary to make a weapon. No, surrounded by specialists, he uses technologies at his disposal (which he can obviously evolve or adapt) to meet specifications. There are, of course, “lone wolves”, but these are ultimately rare when we study their journeys and creations in detail. They are mainly found among the pioneers of this specialty: and for good reason, everything or almost everything had to be invented. Before moving to Izhevsk in 1948 for the production of the AK-47 in 1949, M.T. Kalashnikov carried out the development of his own weapon in…Kovrov, the city of “Tool Factory No. 2” (later renamed V.A. Degtyarev Factory) located about 1000 km east of the Izhvesk where H. Schmeisser was detained. So when M.T. Kalashnikov joined Izhevsk, the AK-47 Type 1, the first variant to actually use stamped sheet metal, was already being developed.

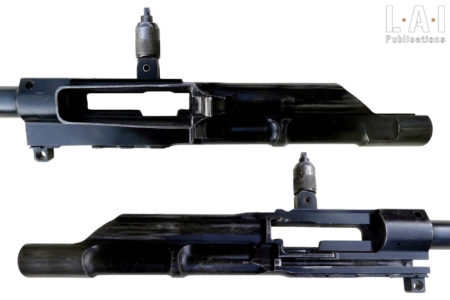

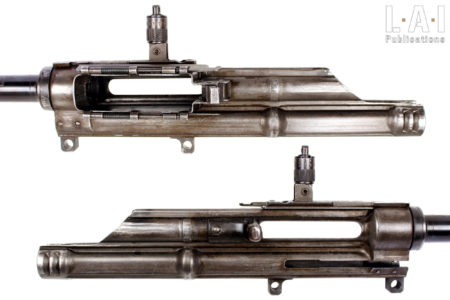

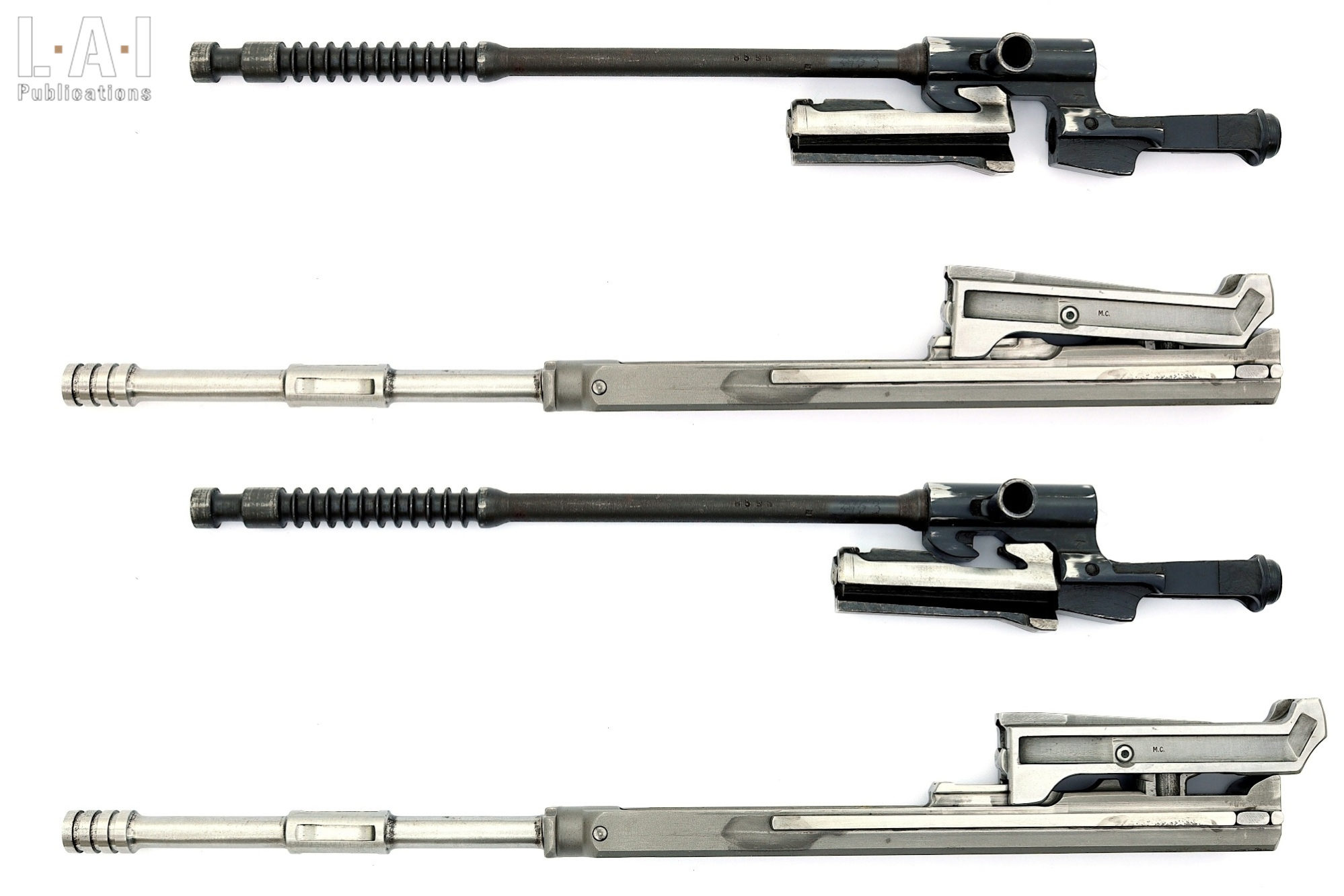

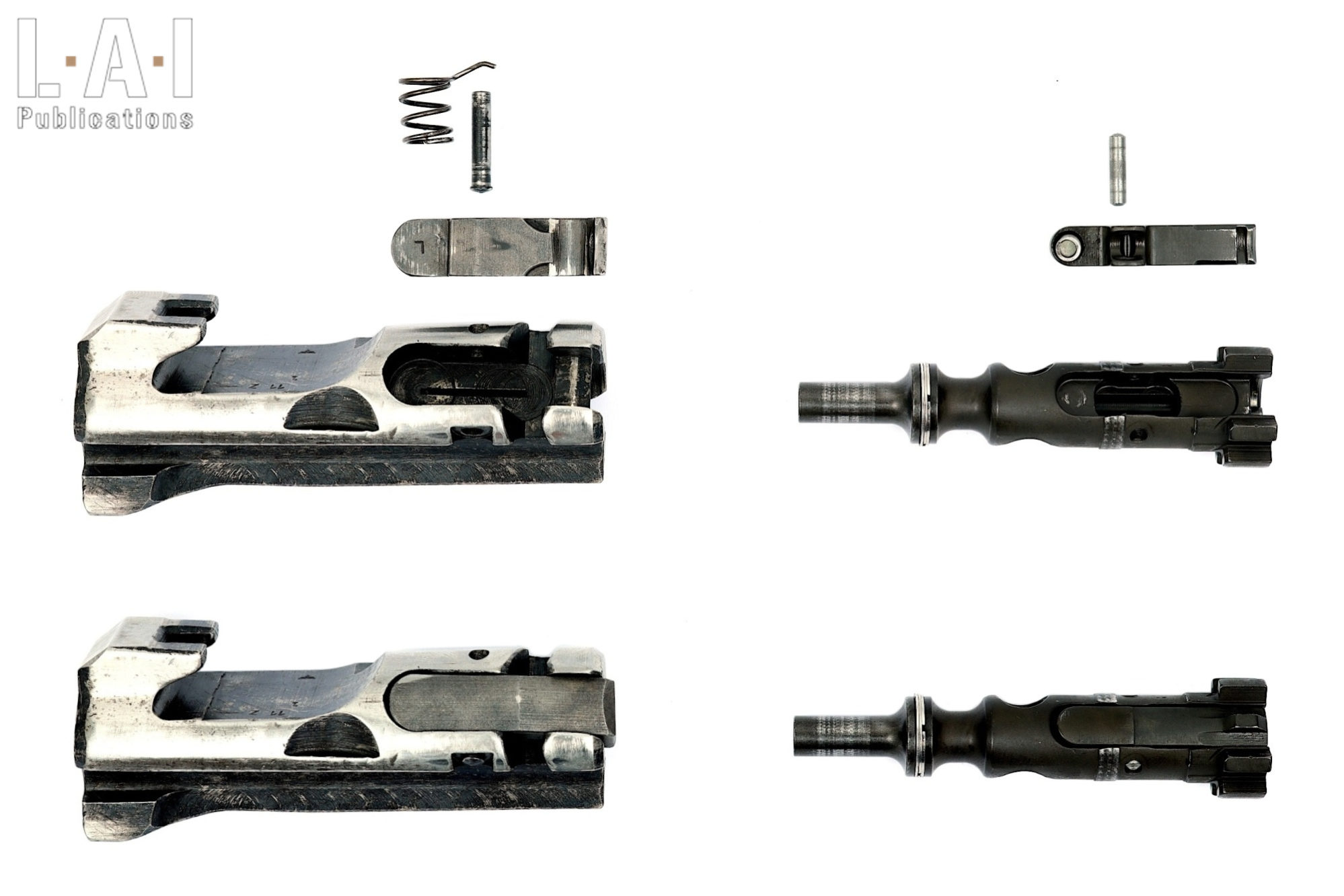

In any case, the use of stamped sheet for construction on weapons of the STG 44 and AK family using stamped sheet metal is radically different:

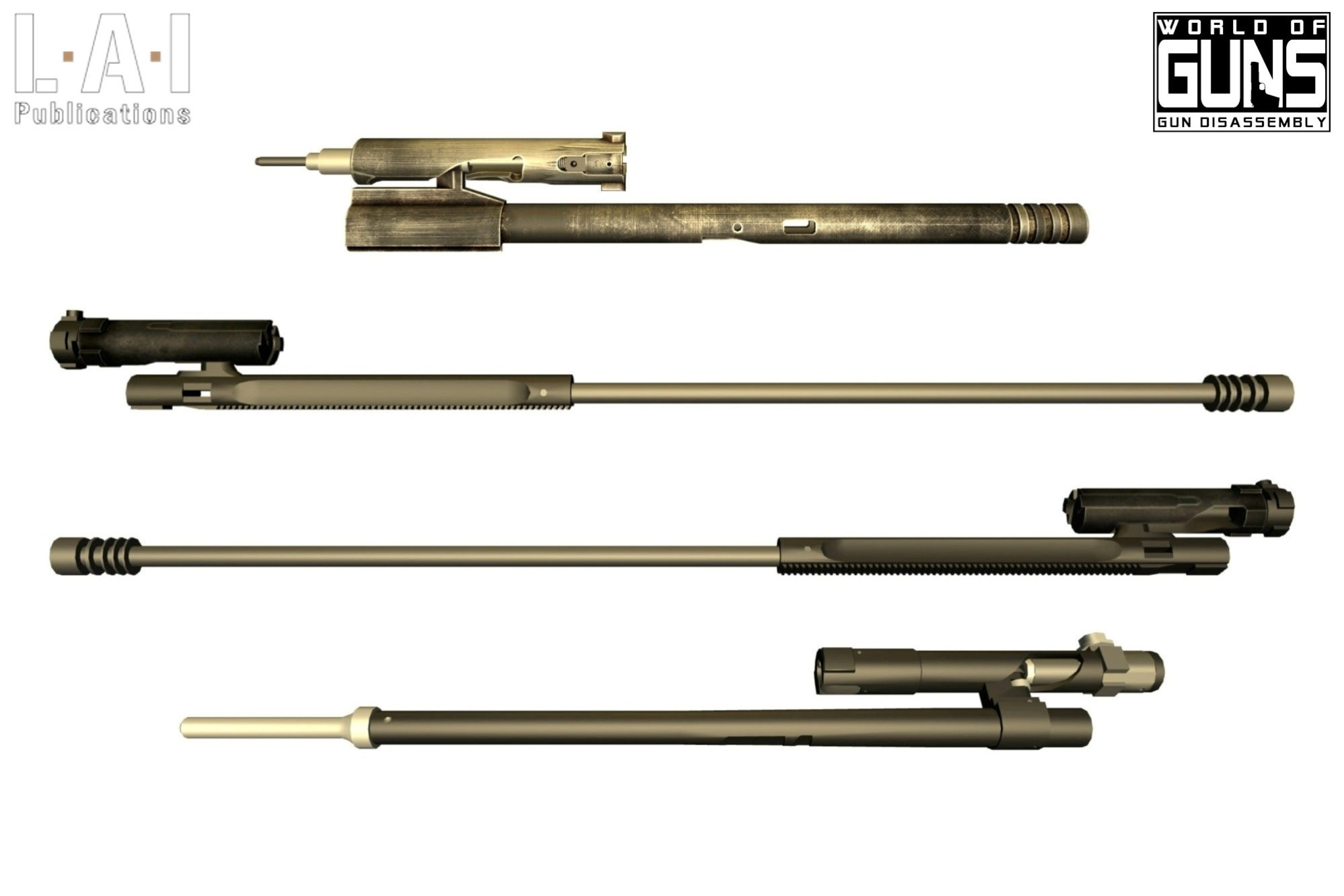

- On the arms of the STG 44 family: it is a shell obtained by stamping a sheet of steel, folded on itself by its middle (which will become the top of the receiver), and welded at its ends (which will become the bottom of the receiver). The guide of the bolt carrier group is obtained by sliding on the walls of the receiver, which are shaped like an “8” (Pic.23).

- On the Kalashnikov variants in stamped sheet metal (AK-47 type 1, then from the AKM): it is a sheet of steel bent in a U-form, therefore open at its top, on which are welded elements that participate in the guiding of the bolt carrier group (Pic.24).

If German technology is part of a rather “tubular” way of thinking that was very common in pre-war Germany, that of the Soviet “U” is very common in the pre-war USSR! It can be found on the weapons of V.G. Fedorov, S.G. Simonov, F.V. Tokarev, some of the weapons of V.A. Degtyarev (the FM DP, but not the PPDs which are tubular) and then during the war of G.S. Shpagin and A.I. Sudayev. On the shape of the bolt carrier group and the “downward” guidance of the bolt carrier group, the influence of F.V. Tokarev with the SVT-38 / 40 seems to us to be significant (Pic.25). On the two Soviet SMGs and S.G. Simonov’s weapon, the “bolt cover” part plays a role in guiding the bolt carrier group, on M.T. Kalashnikov’s weapon as well as F.V. Tokarev’s, it is “just” a protective cover, hence the fact that one can fire without… Finally, by holding your head away from the weapon and just to visualize how it works! On F.V. Tokarev’s rifle, the bolt cover indexes the recoil spring assembly… In any case, don’t shoot without it!

In summary, the Germans’ stamped sheet technology is more “sophisticated”, as it involves more complex shapes, finer tolerances and more specific steel grades. But when it comes to a mass-production weapon, that’s not necessarily a compliment, because it can be less pragmatic from an industrial point of view. It should be noted here that this particular German technology will give a lot of trouble:

- For the engineers at Merz Werke, Louis Stange’s tolerances were much finer than what they were accustomed to using for the typewriter and office furniture that formed the firm’s core business.

- To the Spanish in the design of the CETME (under the aegis of Ludwig Vorgrimler). The versions that could fire 7.62×51 mm “full power” ammunition (i.e. the one adopted by NATO) in a viable way could only be put into production after the Germans at Heckler & Koch had looked at the metallurgy of the frame and the technology of the bolt shock absorber by making the G3 (Pic.26).

Once the receiver manufacturing method has been established, the comparison between STG and AK can be detailed as follows:

- The use of a piston linked to the bolt carrier is present on both weapons, but as mentioned earlier, it is clearly not a German creation. And even on the contrary, they did not really take an interest in gas-operated system until very late compared to other industrialized nations, especially the Soviets. Moreover, in order to make their G43 more reliable, it is the Germans who will – openly – copy the SVT-40 gas-system. On the other hand, the Soviets were already using various gas-system, including piston linked to the bolt carrier with the DP (1927) and SGM-43. But they were obviously familiar with other foreign weapons that used it, including the Garand…

- … which M.T.Kalashnikov himself explained that he had been inspired by for his weapon. Among the similarities with this American weapon, we find a rotary lock, which he and his team have wonderfully designed to remove the fragility linked to the implantation of the extractor found on the American weapon. So nothing to do with the tilting lock of the STG 44 borrowed from the Czech Václav Holek and present on the ZB-26, ZB-30 and BREN (Pics.27 and 28).

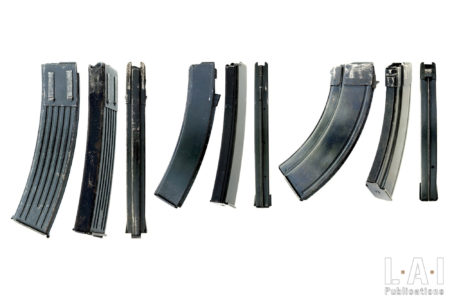

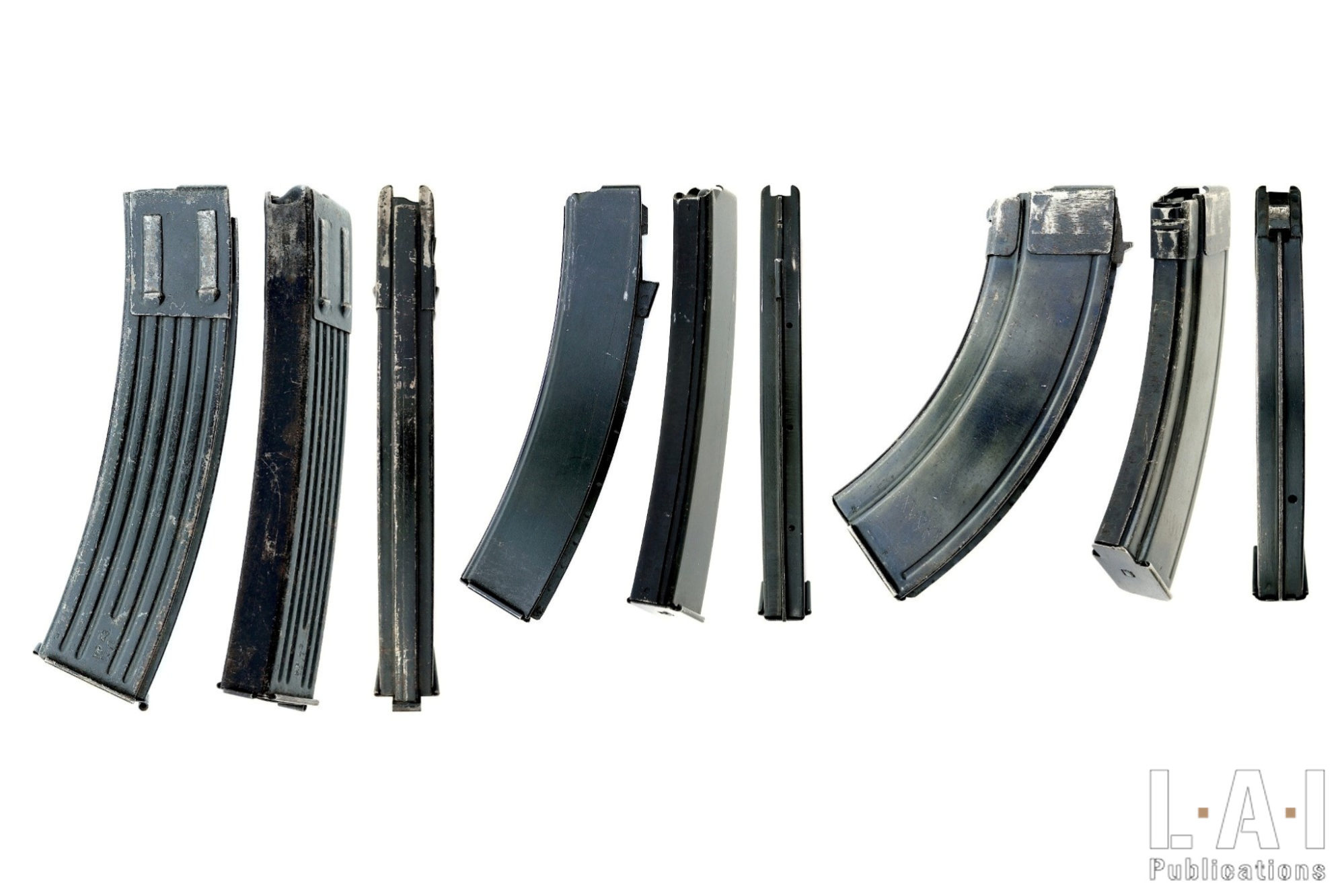

- In the end, the design of the magazines is very different, because as with the caliber, you should not be deceived by the appearance of things, but rather focus on the way they were designed and manufactured. The magazine of the STG 44 uses the same manufacturing method as its receiver: it is a sheet of stamped sheet metal, folded on its front part, and welded on its rear part. The AK one actually uses the recipe of the PPS-43, while being reinforced on the back part of the lips: this was a fragility obviously known on the magazines of A.I. Sudayev’s PPS-43. Thus, it consists of two half-shells assembled by welding: in “plating” on the front, with a ridge, on the back. AK magazines (all variants combined) have a subtility absent from the German weapon: a reduction in thickness at the bullet level. (Pics.29 and 30). Even the ribbing of the sheet metal is different: on the weapons of the STG 44 family, it is in depth, on the magazines of ribbed AK (later than the originals, smooth and of a thicker sheet of steel), in relief. And here too, this is a pattern encountered on the early magazine of PPSh-41: the ribbing is in relief. By the way, it is amusing to note that the Soviets will have a gait with AK magazines, inverse to the PPSh-41 magazine. For PPSh-41, they will first produce them from a thin ribbed sheet, then from a thick and smooth sheet to make them more reliable. For the AK-47, they will first produce them from a thick, smooth sheet metal, then from a thin ribbed sheet to make them lighter. This is not surprising: it is simply the learning of the technology that “comes in”.

- The introduction of the magazine and its locking in the weapon is radically opposed: straight and controlled by a push button in the STG 44 family, the AK family uses a head-to-toe introduction with a locking lever on the rear. The consequences of these choices are set out in Chapter 6 “How weapons work?” of our book “Small Guide for Firearms”.

- Organization of the cocking handle: on the left for the German (as on the German MP 38 and 40, favoring the use of the off-hand of the right-handed shooter, therefore of a majority of users, for the manipulations of the weapon), on the right for the Russians (like all long weapons in the USSR, favoring, for a right-handed shooter, the use of the “strong” hand and encouraging to remove the finger from the trigger for manipulations).

- Sights: The tangential rear sight was in use in both armies long before the outbreak of the WWII. It can be found on the infantry rifle of both countries, the K98k (1934 – but this upgrade was used before on the Karabiner 1898 A, B and AZ and even the Gewehr 1898 from 1920) and the Mosin Nagant 1891/30 (1930). To attribute authorship here seems futile, especially since these are not the first weapons to use this type of increase (they are already found on nineteenth-century weapons). However, unlike the STG 44, which uses the recipe of the Mausers in service (but adapted to its caliber) without further fanciness, the AK uses an innovation also present on the SKS-45 (and probably related to the specifications): the “combat” position. This is an additional position located at the rear end of the rear sight (so easy to find) corresponding to the 300 m position and allowing constant aiming engagement from 0 to 300 m. It should be noted that this is a compromise between the increases of many rifles from the WWI (which started at 400 m) and that of the WWII (which usually starts at 100 m or yards). The front sight on a tower? It is simply related to the presence of a piston on the weapon. Here, too, when you look in detail at the way the parts are made: it’s quite different. Finally, the Soviet front sight is adjustable in both elevation and direction, simply on the ground: this arrangement is totally absent from the German weapon. It should be noted that this last arrangement is not an innovation of the 7.62×39 mm guns: it was already present in a different form on the DP in 1927… Nothing in Germany: the shooting culture is simply not the same (Pics.31 to 33).

- The fire selector of the AK-47 family weapons is copied (or at least, extremely similar! Personally, we don’t doubt direct inspiration.) of the Remington Model 8, with a very different design from the German weapon: here too, the use of the right hand is favored for the right-handed shooter. Funnily enough, M.T. Kalashnikov’s early prototype rifles had selectors very much inspired by the Thompson, with a two-selector organization on the left side (Pics.34 and 35)!

- The firing system of the AK and, as for the MP43/1, MP43, MP44 and STG 44 inspired by the work of John Mose Browning, but in a very simplified way compared to that of the STG 44. The lineage is more obvious on the Kalashnikov mechanism than on that of the STG 44… which is, once again, unnecessarily complex (Pic.36).

- An undeniable German heritage of the Kalashnikov, or at least the folding versions AKS-47 and AKMS, is the folding stock. But it doesn’t come from the STG 44… but from the MP 38 and 40! This type of stock had already been adopted for the PPS-43 and it can be assumed that it was the result, as for the rear sight “combat” position, of the specifications. It should be noted, however, that the matter has been somewhat rethought. However, it was very uncomfortable to shoot, and was replaced with the AKS-74 by a folding stock on the left side of Soviet design (Pics.37 and 38).

- The muzzle of the barrel is threaded on both weapons to receive accessories (such as a Blank Firing Device – BFD – visible in Pic.33). But here too, the borrowing is actually made from the MP 38 and 40 (the MP40 having visibly positively marked M.T. Kalashnikov during the war, at least by showing him the advantages of the SMGSubMachine Gun More – Pic.39). Moreover, threading a pipe is a technical solution that is in no way innovative in the 1940s… It should be noted here that M.T. Kalashnikov’s prototypes were equipped with a muzzle brake and without a thread: it is likely that this was imposed on him to satisfy the need for the BFD and because the muzzle brake was considered superfluous and generated auditory discomfort when shooting.

- The disassembling of the two weapons is very different: better than words… in pictures (Pics.40 to 46)! This obviously stems from the differences in the manufacturing choice already mentioned. It also drastically changes maintenance operations in the field. Anyone who has had to maintain a weapon from the AK family and a weapon from the G3 family (very close to the STG 44 when it comes to receiver accessibility for cleaning) knows how much more pleasant the AK is at this level. Added to this that on an STG 44… The gas tube does not disassemble! Like the cocking lever tube of a G3…which is reminiscent of the STG 44 gas-tube.

- The stock angle of the AK-47 (Type 1 to 3) allows the sights to rise in the natural alignment of the eye when the weapon is shouldered. In doing so, the weapons tends to climb when shooting more widely than a weapon with a “zero” stock angle (such as the STG 44) favoring the alignment of the barrel on the shoulder. This shows that M.T. Kalashnikov did not think in the same way as the Germans here. This provision was finally adopted from the AKM, although it is not clear whether this evolution is the result of internal feedback or foreign inspiration. Both are quite possible, and as already mentioned, the question of the alignment of the axis of the barrel in relation to the shooter’s shoulder is not exclusive or an innovation of the STG 44 (Pic.47).

Paradoxically, the similarities (some of them disturbing) with the AR-10 and AR-15 are more numerous:

- Large diameter recoil spring in the stock of both weapons (partially in the case of the STG, totally in the case of the AR-15 – visible in Pic.45). We do, however, think it is more “inspired” by the work of Melvin Johnson than by STG 44.

- Dust cover of the ejection port is very close. In fact, its origin actually comes from the MG42… but still, the resemblance to the STG 44 is uncanny! (Pics.48 and 49).

- Introduction of the magazine in an identical way, with a literally… copy/pasted locking system (Pics.50 and 51). One difference, however, is the lateralization of the control. On the German weapon, it requires the use of the left hand of the right-handed shooter, thus favoring the recovery of the magazine by the hand that controls its unlocking. On the AR-15, the control is arranged on the other side of the weapon, allowing a right-handed shooter’s right hand to unhook the index finger… and thus “promoting” its ejection more than its recovery. This last point does not seem to us to be a good idea: a magazine is intended to be re-used, and not to be “consumed”.

- Hinged weapon organization with pin disassembly. Again, as far as we know, the thing did not technically exist in the United States before the advent of the AR-10 (visible in Pic.45). As a reminder, the receiver of the first AR-10 prototypes was… in steel, and in particular, for the second prototype in sheet metal.

- An extractor strangely similar, with a disassembly… possible in both cases using the tip of the firing pin (Pic.52)!

- Less significantly, the fire selector located in the same location as the STG 44 safety. This may seem trivial, but it is rather a break with the habits of American weapons, although the BAR 1918 has a selector located in this place…(Pic.53)

So clearly, we won’t say that Stoner is copying the STG 44: that would be totally stupid. But the “potential direct borrowings” are simply more numerous and more obvious than on the AK-47.

The paradox in the trial (not to be doubted, always tinged with ideology as already mentioned…) which is often done with the weapon of M.T. Kalashnikov… well, it’s that the weapon has much more inspirations on the other side of the Atlantic (on the West, and of the Bering sea on the East) than in Germany! Moreover, it seems important to us to mention here that M.T.Kalashnikov seemed to have retained a certain resentment against the Germans in the immediate post-war period (a personal impression that we had when reading his biography) and a certain sympathy for the Americans. Although he probably did not hesitate to study their productions (MKb42(H) N°503 was on V.A. Degtyarev’s desk as early as 1943… and not to do so would have been a mistake in this area), one wonders if he did not make a point of borrowing as little as possible from German technologies. Other Soviet designers did not hesitate to borrow from the Germans: the feeding system of the RPD-44 and the links of these belts were obviously totally derived from those used by the MG34 and 42. Similarly, the Makarov pistol borrows a few small patterns from the Walther PP and PPK. On the other hand, presenting the Makarov pistol as a derivative of the Walther PP/PPK on the pretext that it shares the same crude disassembling mode… is once again an intellectual shortcut that brings us one step closer and closer to ignorance… Yours truly’s article on this subject is also available on this same site in link here.

The production heritage of the STG 44, clearly, is the CETME / G3 families, through the Gërat 06(H), STG-45 and CEAM-50… neither AKs nor ARs. In the last two cases, we are dealing with “indigenous” conceptions, which borrow from many weapons from various backgrounds, for better or for worse… It can also be noted that in certain aspects (technical and ergonomic), the STG 44 has most certainly inspired… the FAL! The first versions of the Belgian weapon had been chambered for the .280 British and for the… 7.92×33 mm! But you should also be aware that the weapon also borrows from the SVT-40 as well as other weapons. Dieudonné Saive, too, has done his job well: drawing inspiration from what already exists to produce a solution in line with his specifications.

And that’s what the job of a weapon designer consists of, in our opinion: it’s not rocket science, but simply about offering a tool (in this case, a weapon) that is viable in all its aspects in the intended use: military or civilian. To this end, surrounded by a team of specialists from various fields, he gives guidance and arbitrates decisions.

In Conclusion

It is evident that the Germans were during this period extremely active and inventive in armaments. The mere fact of stating it is even a shameless truism… Through this creativity in the service of a warmongering state, their conceptual influences in the military field for the decades to follow would be considerable, especially in the West. Small-arms will be no exception. However, when we look in detail at the work in this field in Nazi Germany, we see a glaring lack of state dirigisme. This may seem paradoxical in a totalitarian state, but it is forgotten that it was built with the support of liberal industrialists. While this is certainly one of the keys to their creativity, it comes at the price of a cruel lack of pragmatism in many areas. The work went in all directions in a waste of time and resources that was more than problematic, especially in times of war. Other nations will be better able to steer their boats, by focusing their production in accordance with the existing capacities in their countries: the United States comes to mind, of course, but also of the USSR or Great Britain.

But in reality, we should not credit them with the paternity of this or that foreign weapon, we should probably rather consider it on a global dynamic: like the race to the moon. Everyone spies and sometimes, copies or takes inspiration from everyone else. In this time capsule, the WWII, in our opinion, the two protagonists are the two most engaged in the war, namely the Germans and the Russians. The Americans and Europeans were very creative until the dawn of the WWII, but the war boosted the creativity of the Russians and Germans, probably because it was the two countries, still in possession of their means (this was not the case of France for example) the most impacted by the war. The design of a firearm is always based on the study of already existing work – and this is arguably true for any design. From that point on, you shouldn’t take credit away from a brilliant design wherever the ideas come from.

Finally, it seems to have become customary when talking about the FG 42 to give one’s personal feeling about the weapon: for my part, and after having disassembled and fired the E and G models, I am clearly not transcended. And I apologize to my excellent friend Pierre Breuvart, who is convinced of the superiority of the weapon over its contemporaries. Of course, you can be friends… but not of the same opinion! And yet, like many, discovering this weapon is for me one of my childhood dreams: myth is omnipresent in literature. If the FG 42s made a positive impression on us, it is only because their disassembling (even at an advanced level) is extremely accessible (Pic.54). On the other hand, the STG 44, which we also disassembled and fired, is clearly for us the most impressive weapon of the WWII. From my point of view, it is simply one of the last great revolutions in small-caliber armaments.

Arnaud Lamothe

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!

Thanks:

Pierre Breuvart to share with me his knowledge and passionate reflections on the subject.

Gilles Sigro, for sharing his passion, a source of inspiration for me.

Yann, still at the post!

The ESISTOIRE Gunshop for the provision of some of the materials presented in this article.

Selected Bibliography:

- “Sturmgewehr! From fire power to striking power”, by Hans-Dieter Handrich, published by “Collector Grade Publications”.

- “Death From Above. The German FG42 Paratrooper Rifle”, by Thomas B. Dugelby and R. Blake Stevens, published by “Collector Grade Publications”.

- “The Last Enfield. SA80 – The Reluctant Rifle”, by Steve Raw, published by “Collector Grade Publications”.

- “The World’s Assault Rifles”, by Gary Paul Johnston and Thomas B. Nelson, published by « Ironside International Publisher, Inc. ».