Submachine guns hold an important place in the of Italian small-arms history. The Villar Perosa is considered by many as the forerunner of this category. According to the sources, the SMGSubMachine Gun More concept would be finalized at the end of WWI, either by the direct descendants of the Villar Perosa, the OVP M1918 and Beretta M1918, or by the German MP-18/I… The title is contested within a very short timeframe: only a few months! During the interwar period, Italian industry would not be left behind in terms of creativity, especially in terms of machine guns, light-machine guns, but also submachine guns, with, in particular, the excellent (although ultimately expensive and cumbersome!) MAB Mod. 38.

Background

The Italian small-arms industry has long flourished, both in the civil and military fields. Its epicenter can be located around the cities of Brescia and Gardon-Val-Trompia, two cities only 20 km apart and part of the Italian industrial center formed by the Turin-Milan axis. This dynamic industry is characterized above all by a multitude of companies of different sizes.

The submachine gunSubMachine Gun More adopted by Mussolini’s Italy was the Moschetto Automatico Beretta Modello 38 (Beretta Model 38 Automatic Musketoon) also called MAB Mod.38 described in detail in the article of Luc Guillou. As its Italian name suggests, it is in its design more of an automatic carbine than a “submachine gun” in the sense we understand this word today. This consideration is subject to debate, but the weapon is heavy and bulky: announced at 4.2 kg for a length of 946 mm (nearly one meter!) including a barrel of 315 mm (for a 9×19 caliber … maybe a length record with the KP-31!). The dimensions of this beast are close to a contemporary assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More. However, this is quite usual before the beginning of WWII, and would finally only be questioned with the advent of the French MAS-38 (more compact and lighter although without folding stock) but especially by the very “modern” German MP-38 (one of the firsts service weapons with a folding stock) … adopted the same year as the MAB Mod.38.

The manufacturing methods of the Beretta weapon also remained in line with the standards of the era: when it was put into production, a majority of the parts were made by milling. The weapon would undergo many variations, in particular in order to simplify its production. In any case, the weapon remains faithful to its base, heavy and cumbersome, especially regarding its use.

The FNAB-43

It is undoubtedly possible starting from this observation that the FNAB-43 was born, “FNAB” standing for “Fabbrica Nazionale d’Armi di Brescia”, National Weapon Factory of Brescia, in the language of Dante Alighieri. The prototype would have seen the light of day in 1942 at the Società Anonima Revelli Manifattura Armiguerra in Cremona for a production by the FNAB generally announced between 1943 and 1944 to about 5000 or 7000 copies depending on the sources (Pics.01 and 02). At the same time, Beretta offered the “Modelo 1“, with some similar features. The weapon has indeed a global aspect closer to our current standards: a 20 cm barrel, a folding wired stock and a total bulk (width included) more compatible with the use that would be made of this type of weapon: close-quarter combat, defense weapon for vehicle crews and more generally weapon of “defense” for units whose primary vocation is not infantry combat. More curious, especially for its time, the weapon fires from a closed bolt and operates with a mechanical advantaged blowback … But we will come back on each of these points. The weapon still retains some similarity with its predecessor: it is mainly made of machined steel and uses the same caliber (9×19). It uses the same double-stacks / double-fed magazines.

The choice of manufacturing methods, if it may seem obsolete when the weapon was born, is undoubtedly a pragmatic choice regarding the situation of Fascist Italy in the middle of WWII. At first glance, the use of stamped sheet metal (as in Germany, the USSR, but also a little later in the United States of America, which would ultimately rarely use this method of manufacture for their small arms) seems more in tune with the times. Actually, this technology, which was then relatively innovative, could not be improvised and facing urgent needs, the use of perfectly mastered and available manufacturing methods was not absurd. It is also the choice that would be made in the early 1950s by the Soviets with the cessation of the manufacture of the AK-47 Type 1, in stamped sheet metal, to manufacture the Types 2 and 3, forged-milled steel … at least the time to “refine” their final sheet metal model, the AKM in 1959. This choice is all the more rational if manufacturers do not encounter raw materials shortage or if the solution adopted allows a substantial reduction in the consumption of this same raw material. While the difficulties of supplying raw materials in mid-war Italy seem obvious, a comparison between the MAB Mod.38A and the FNAB-43 seems to indicate that the latter is less greedy than the former. We do not have numbered sources, however, the receiver is shorter and thinner, the bolt carrier group (BCG) lighter… and the finished weapon finally lighter: without magazine, only 3,079 kg (on our scale). A weight slightly lower than that announced for the MAB Mod. 38/42 and 38/44, at about 1 kg less than the MAB Mod.38A. The dimensions are also to the advantage of the FNAB-43: the parts being overall more compact and thinner (the weapon is only 33 mm thick at the receiver), indeed the blanks are also smaller … Thus, they are less greedy in raw materials and less greedy in machining time.

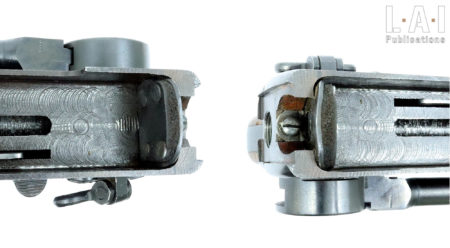

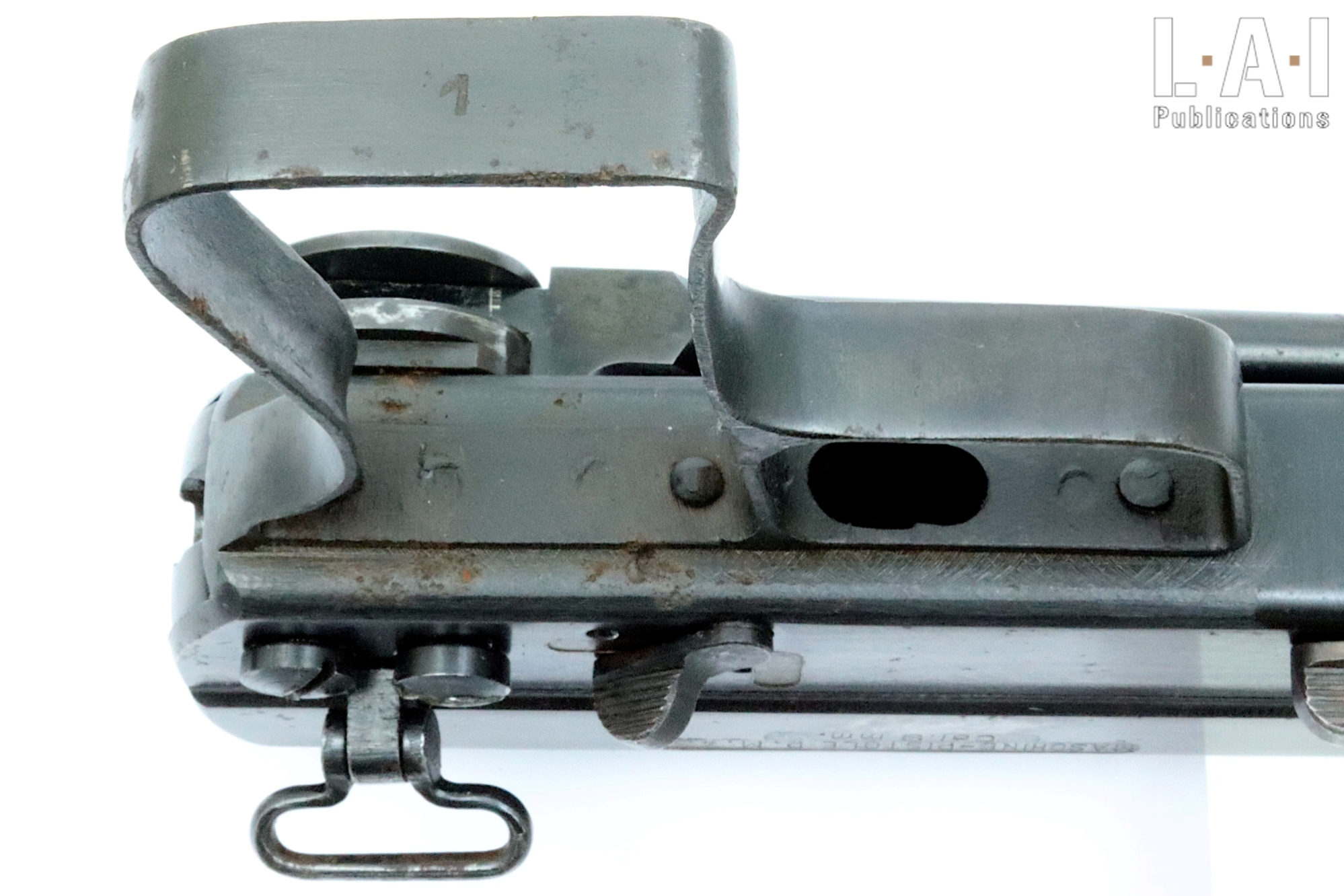

Before going into the details of the production of the weapon, it is necessary to specify that they are 2 known versions: we will informally call them the ” Type 1″ (early) and “Type 2” (late). In addition to differences in marking, the Type 2 presents simplifications of production that we will detail (Pics.03 to 05). In general, the Type 2 raises some questions… But everything in its own time: all this will be discussed later in the article, after a formal presentation.

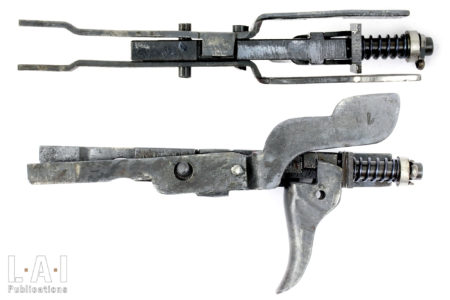

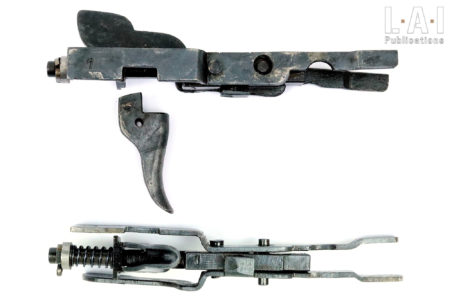

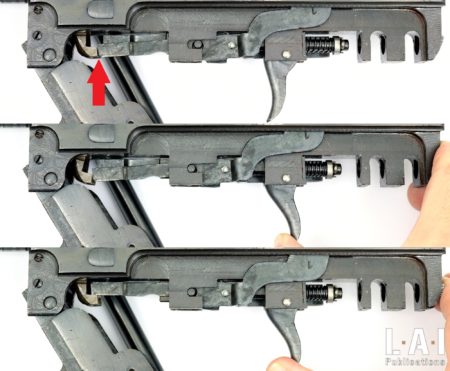

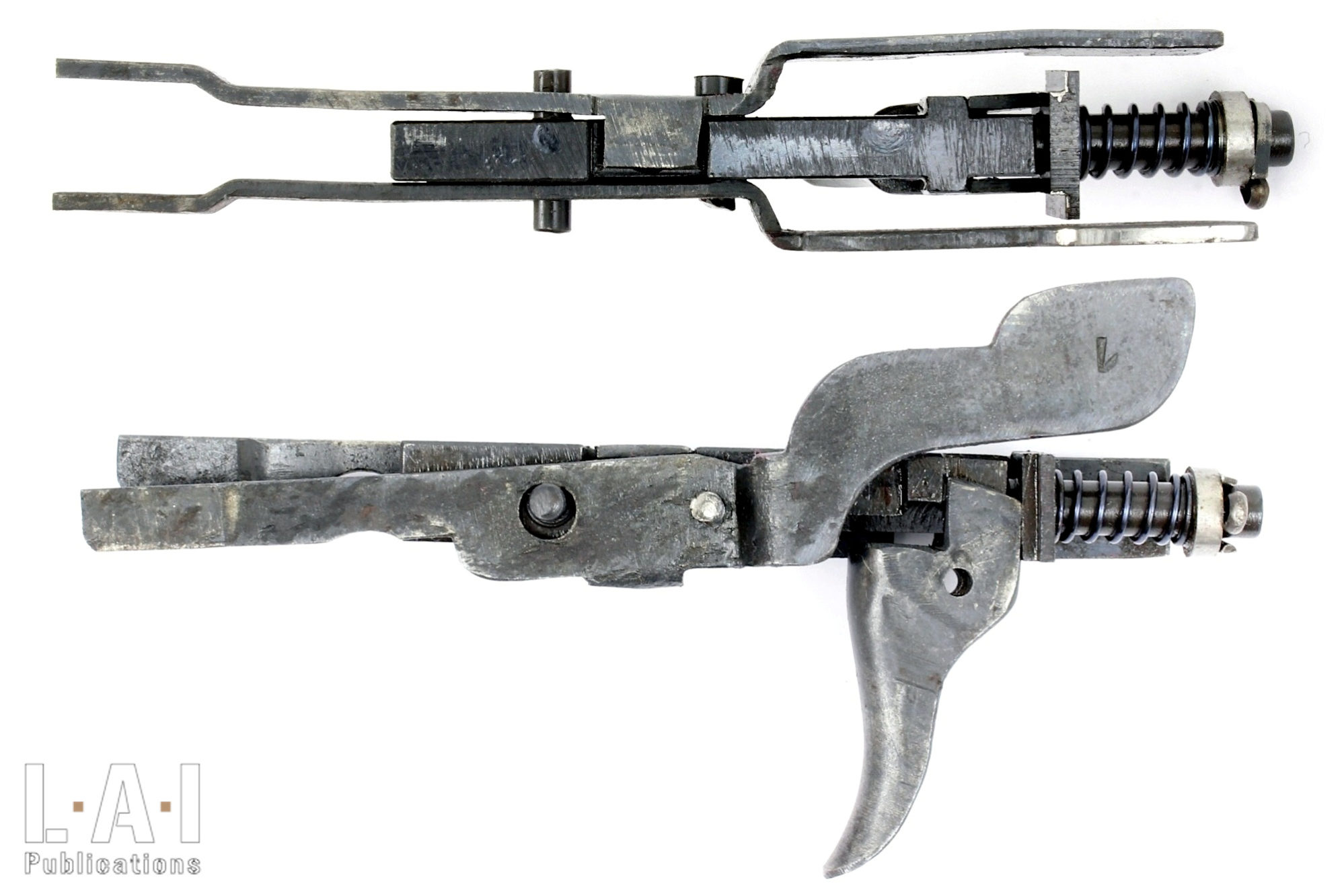

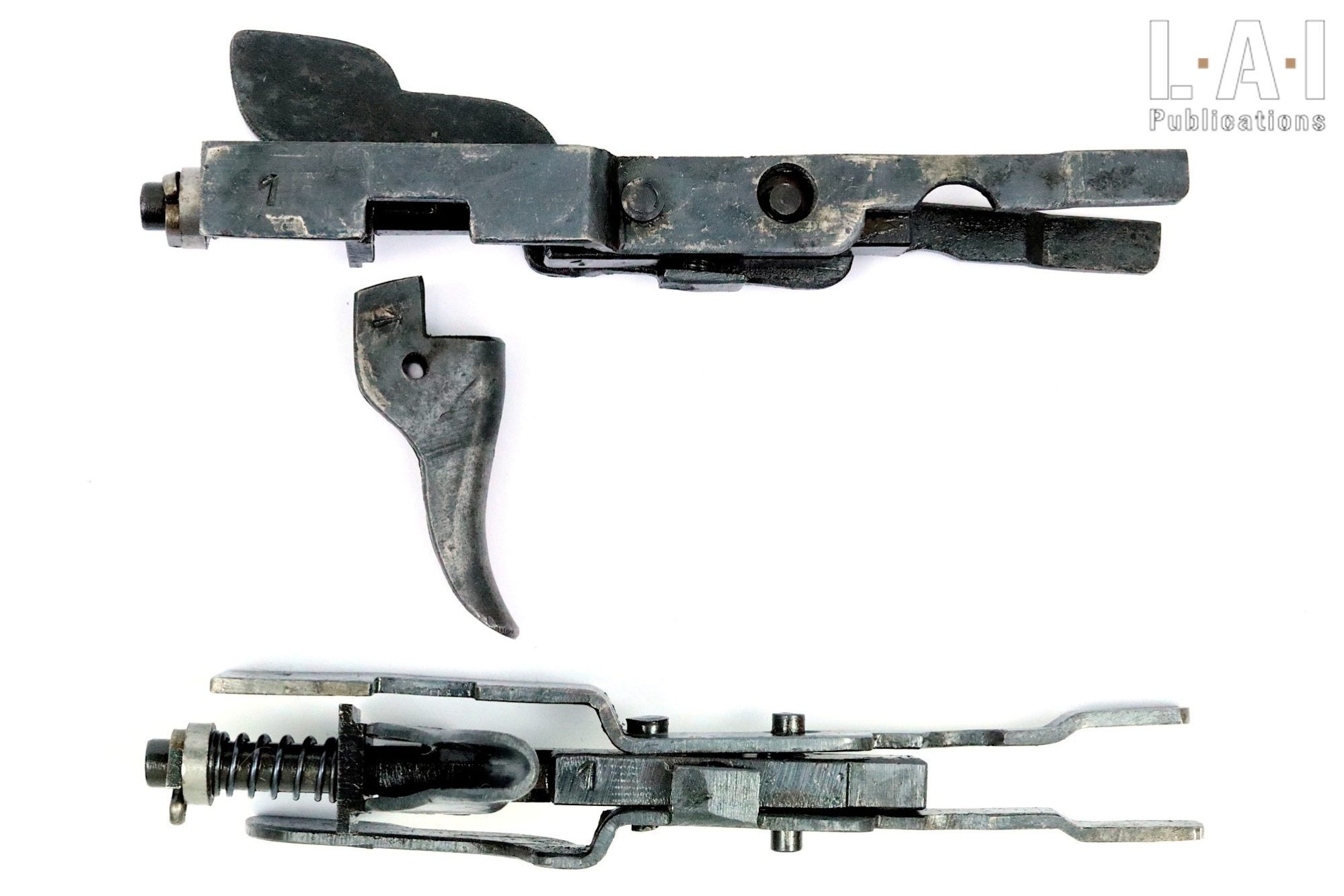

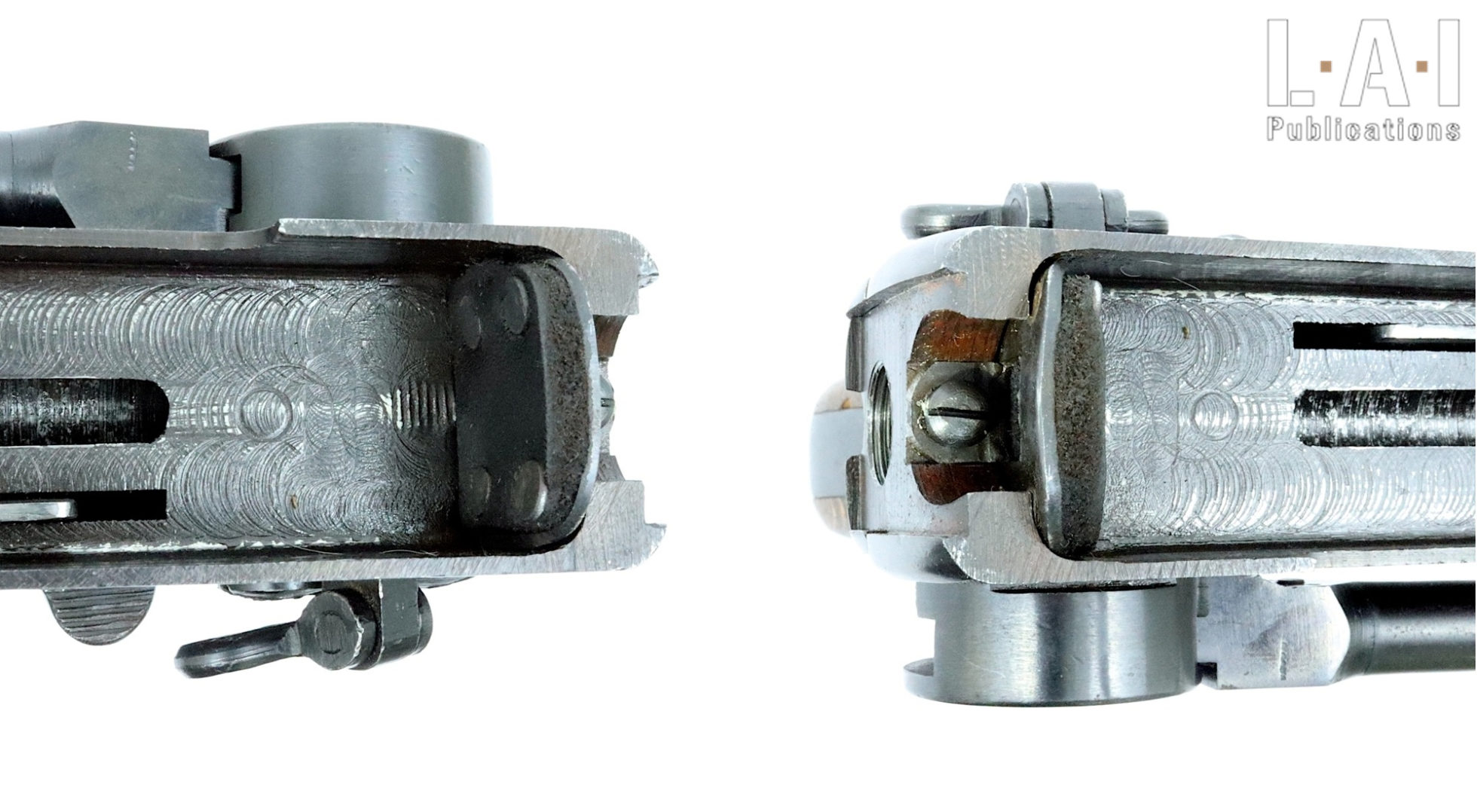

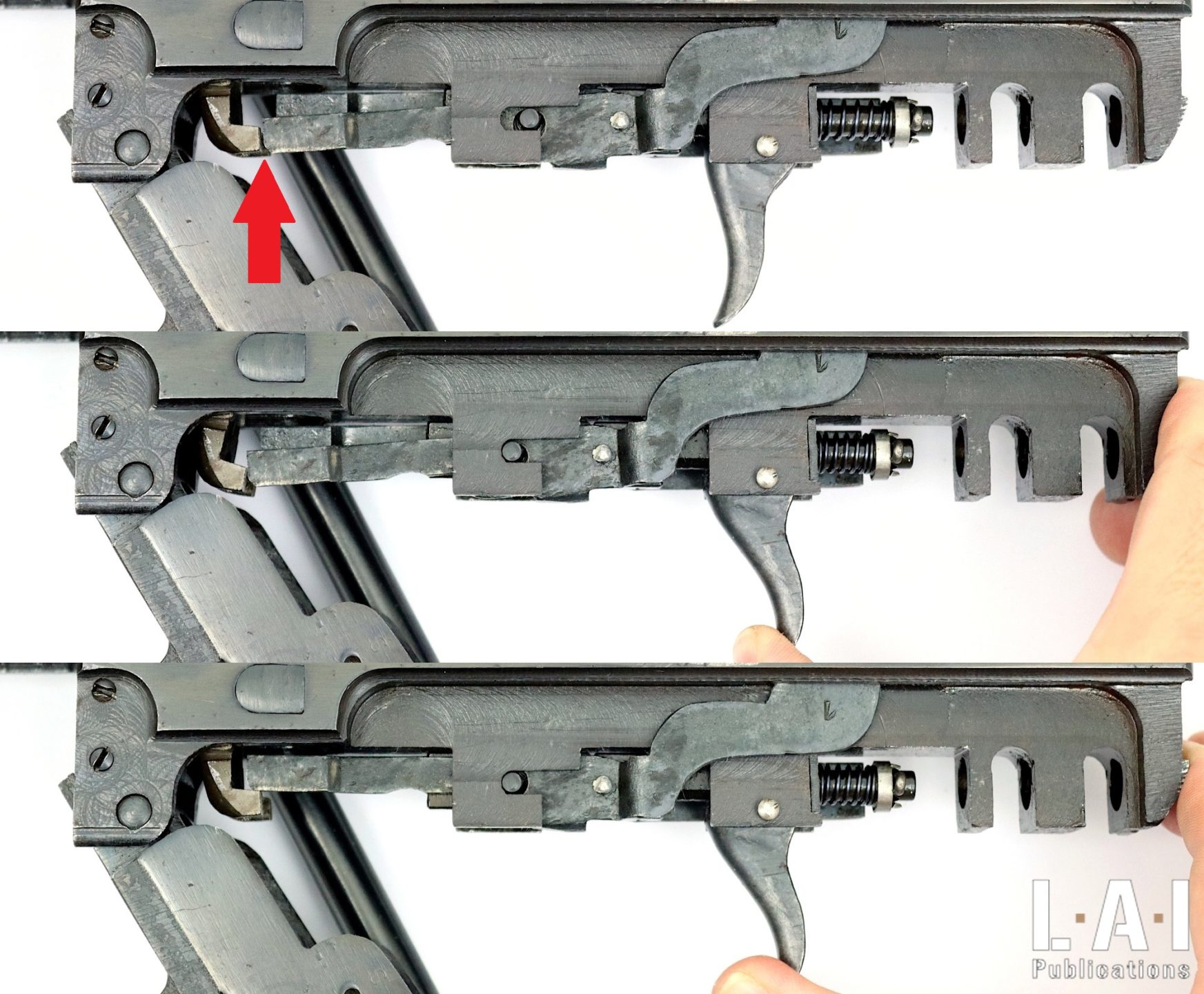

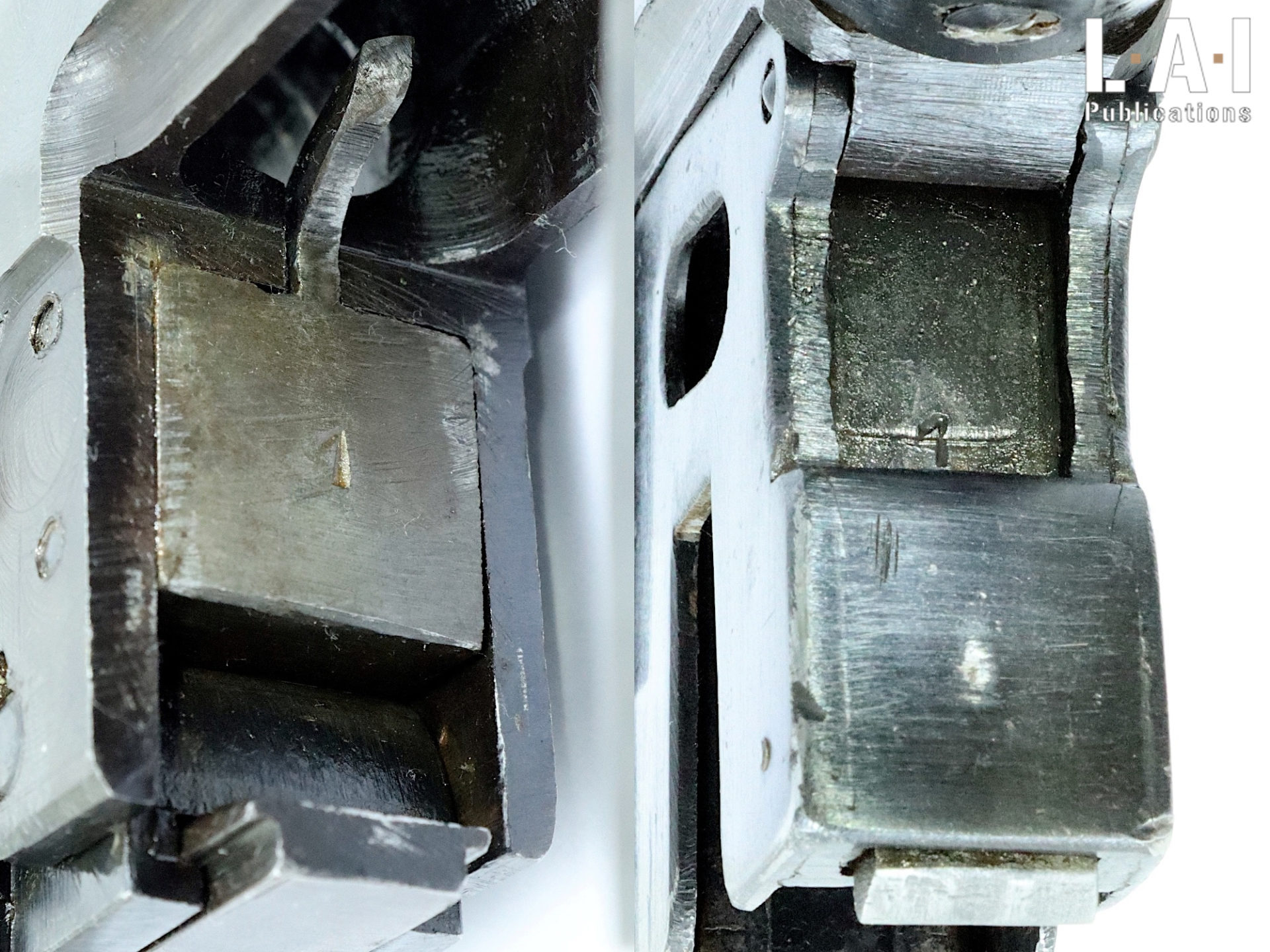

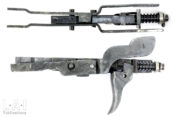

In detail, on the Type 1, the receiver, pistol grip and magazine well are machined in very reasonable size blanks. The machining sequences seem rather simple for these parts: there are only a few “complex” shapes requiring convoluted machining operations. If the pistol grip of the Type 1, of rounded shape, is fully machined, the Type 2’s, of angular shape, is brought back by riveting and spot welding on its frame (Pics.06 and 07). It consists of folded and welded sheet metal. Similarly, the Type 2 magazine well is a simplified production: it is the assembly by welding of several small stamped and machined parts. The receiver cover is made of sheet metal, the rear sight being brought on it by welding. The barrel shroud is a thin extruded tube on which cylindrical openings are punched. It ends with a muzzle brake/climbing compensator … whose shape reminds the PPSh-41’s! (Pic.08) The parts of the trigger mechanism are mainly made of sheet metal: small parts, not really subjected to a lot of stress, “easy to produce” (Pic.09 and 10). The MAB Mod.38’s and its derivatives were made of machined steel.

A point often put forward arouses our curiosity: it is often stated that the weapon requires a “precise and careful manufacture”. Let’s be clear, no more than any other… and maybe less than others! One could cite here the thoughtless adjustment (for a weapon of war) of an MG 34 or a P.08 … or even a Thompson! Admittedly, these weapons are a little older. In the FNAB-43 of Type 2 at our disposal, the BCG “floats” in the receiver and the internal finishes are coarse (Pic.11). The parts of the trigger mechanism, too, are made in a rather rough way and their design, with a “drawer sear” (we will come back to this), dispenses with precise machining as some cocking notches can be. Similarly, the choice of the use of a mechanical advantaged system (we will also come back to this!) does not seem to us to be an incoherent choice from an industrial point of view. Indeed, the use of the inertia amplifier lever does not impose insurmountable technical constraints: it seems that it is for this reason that it was chosen in France to the detriment of rollers system, yet heavily studied after the war (with for example the AME 50). Be careful not to confuse “adjustment” and “empty space”: the weapon is intended to be compact, there is little space without mechanical utility.

An implementation that steps away from its predecessors

The weapon has considerable differences with the SMGSubMachine Gun More of the Gardonne-Val-Trompia firm. The real common point remains the positioning of the magazine release at the back of the magazine well. There is still a significant ergonomic difference: the control is very “low profile” on the Beretta, while here it has a real big latch. There is also a production difference between Type 1 and Type 2 (Pics.12 and 13). The magazine is inserted straight into the well which presents the magazine at a slight angle to the barrel in order to facilitate feeding. As on a later MAT-49, the magazine well can be folded (with or without a magazine engaged) to the front of the barrel to facilitate weapon transport (Pic.14). The unlocking of the magazine well is done by means of a wide control located between the trigger guard and the magazine well (Pics.12 and 13… again!). The well then attaches to the barrel shroud by means of a pusher driven by a spring (Pic.15). When deployed, the magazine well serves as the front grip. As mentioned, there is a difference in manufacturing between Type 1 and Type 2: the first is fully machined, while the second is made by assembling sheet metal welded on some machined parts (Pics. 15 and 16).

The double trigger of the Beretta SMGSubMachine Gun More gives way to a single trigger with two levers: a safety at the front and a selector at the rear (Pics.17 and 18). If the choice to keep the selective fire can question, it allows to keep a considerable control over ammunition consumption… A rather sensible thing at a time when ammunition was scarce. In addition, as already mentioned, the firing system is not very complex. Of course, it is always more complex than the provisions allowed by a striker fixed in the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More, firing from an open bolt and automatic fire only. But the couple “firing from a closed bolt” and “single mode” is much more effective!

The cocking handle is attached to the BCG: to the additional mass to be more precise, a logical thing for this type of mechanism… otherwise it amplifies the effort to cock! It protrudes on the right side of the weapon (Pic.19). It is therefore of a reciprocating type. The path of the cocking handle does not have a shutter device… Grime is therefore free to enter the weapon… Something that seems to us not very pragmatic given the internal mechanical arrangements, without space (we pay here for the compactness of the weapon …). The weapon has a folding stock: it pivots under the bottom of the weapon. It is manipulated by pulling the stock wire out of the pivot, quite easily. Its butt plate swivels without locking (Pic.20). We finally find a “real” pistol grip.

The slings rings are arranged on the left side of the weapon, at the front on the front sight support, at the back on the receiver, with the strange possibility of rotating 360 °! There may be something we are missing, but we do not see the need for this provision… It may simply be a matter of simplifying manufacturing.

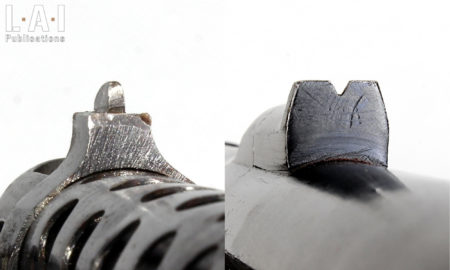

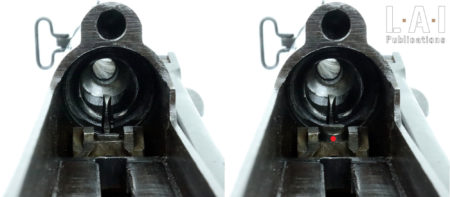

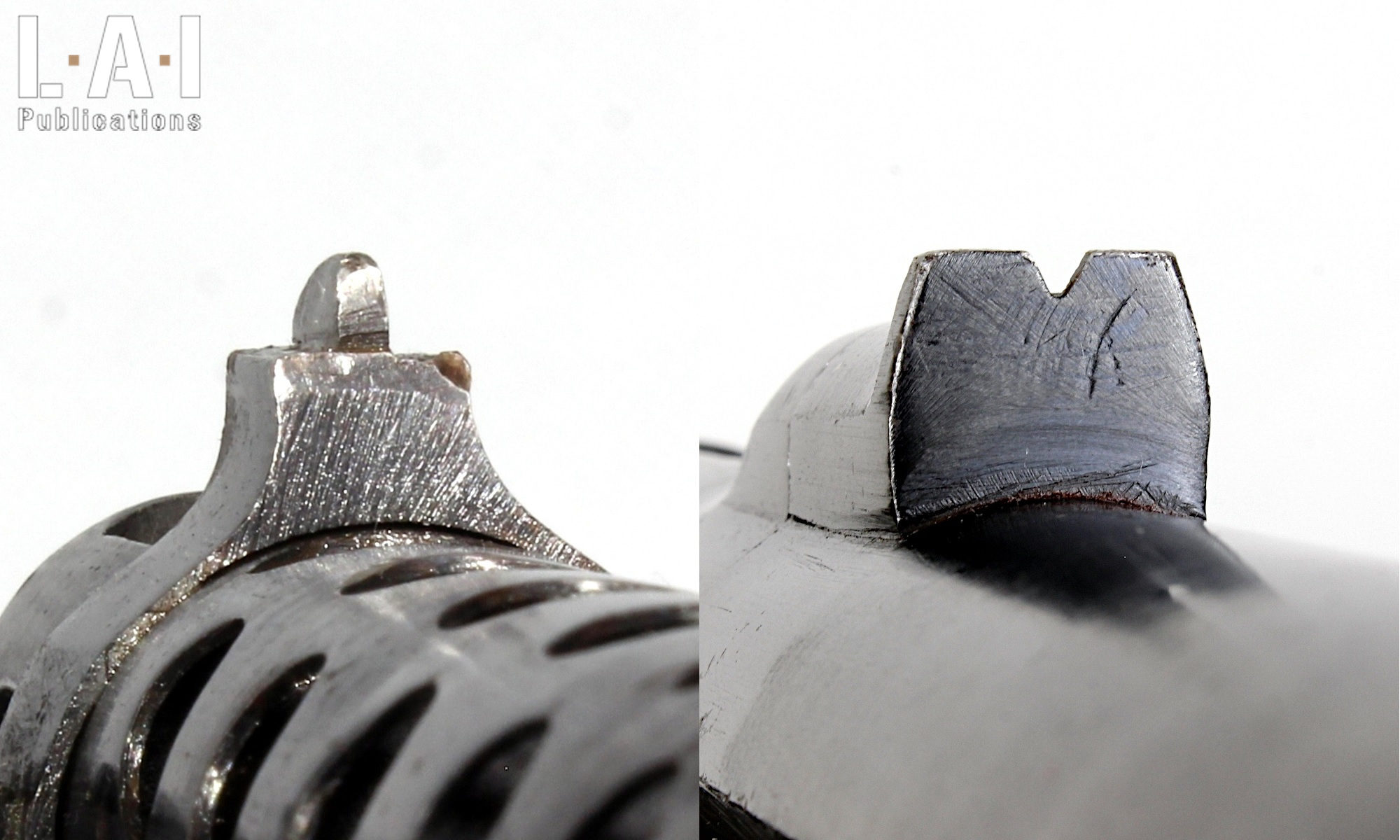

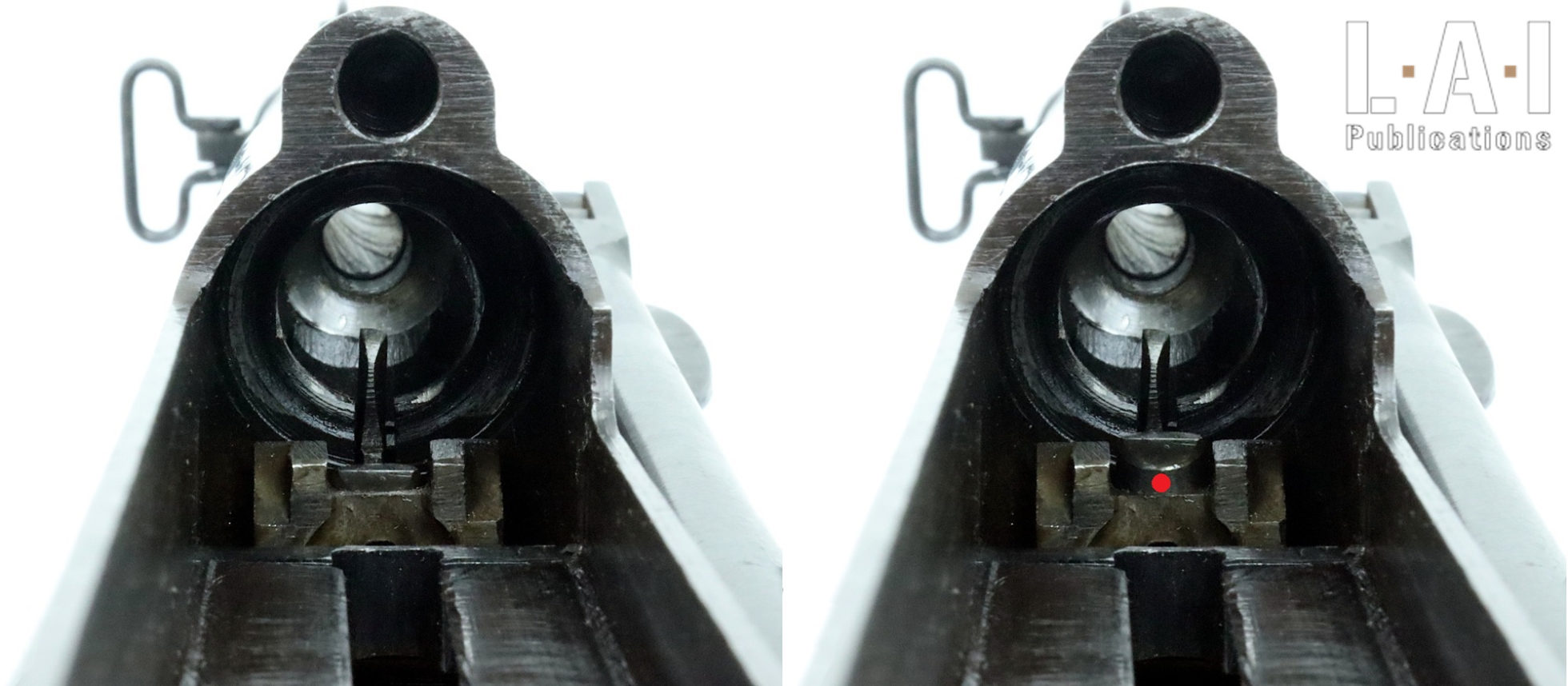

The sights consist of a V-shaped rear sight notch a front sight blade assembly that does not have any adjustment arrangement (Pic.21). If the front sight is mounted on a dovetail, it is obvious that on our Type 2 copy, this is a construction layout, and not a possibility of adjustment as can be seen in Pic.22. When you are used to properly adjusting your weapon for shooting, the absence of this possibility is cruelly felt: you are forced to lead the shoot constantly … But we’ll talk about this again in our consideration about shooting. Note that this “hardiness” is quite common on SMGSubMachine Gun More (and sometimes even LMG!) of this period… except in the USSR! Another disturbing point, the sights, although “massive”, have no protection.

A mechanic, also taking another direction

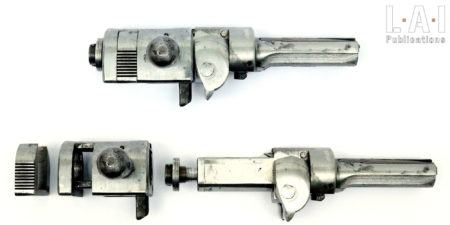

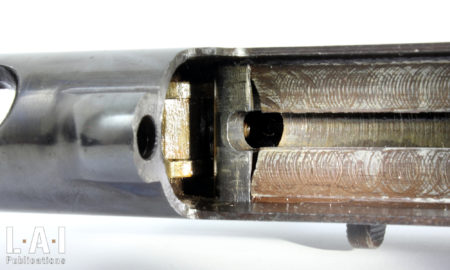

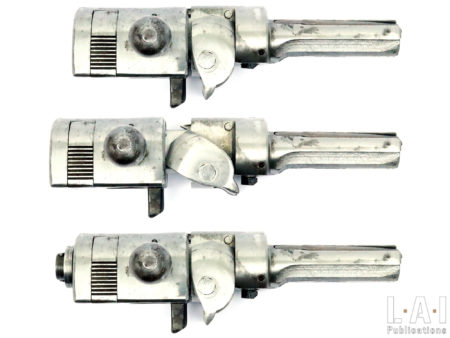

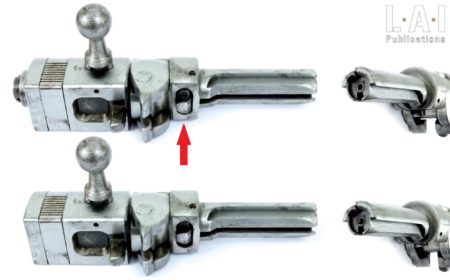

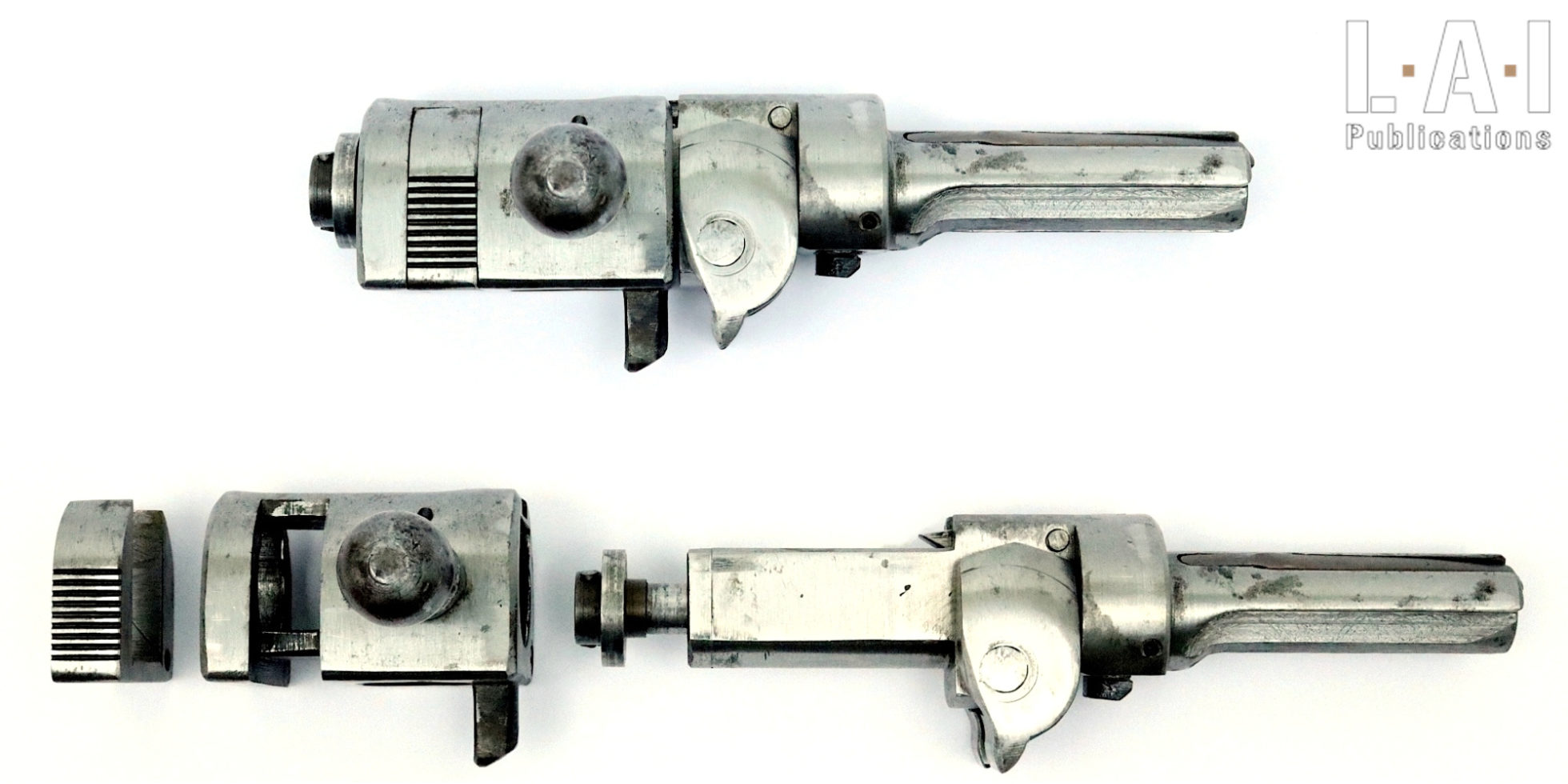

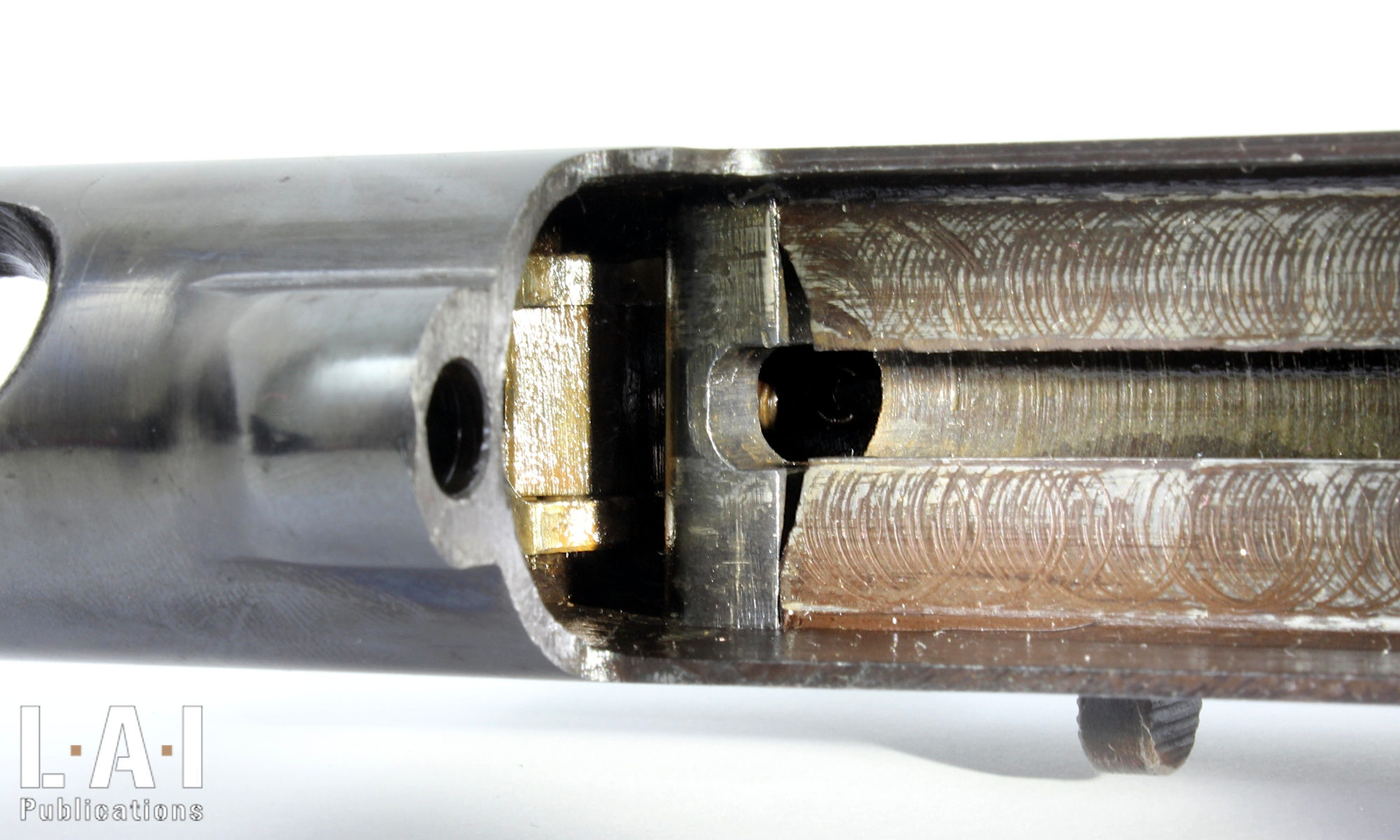

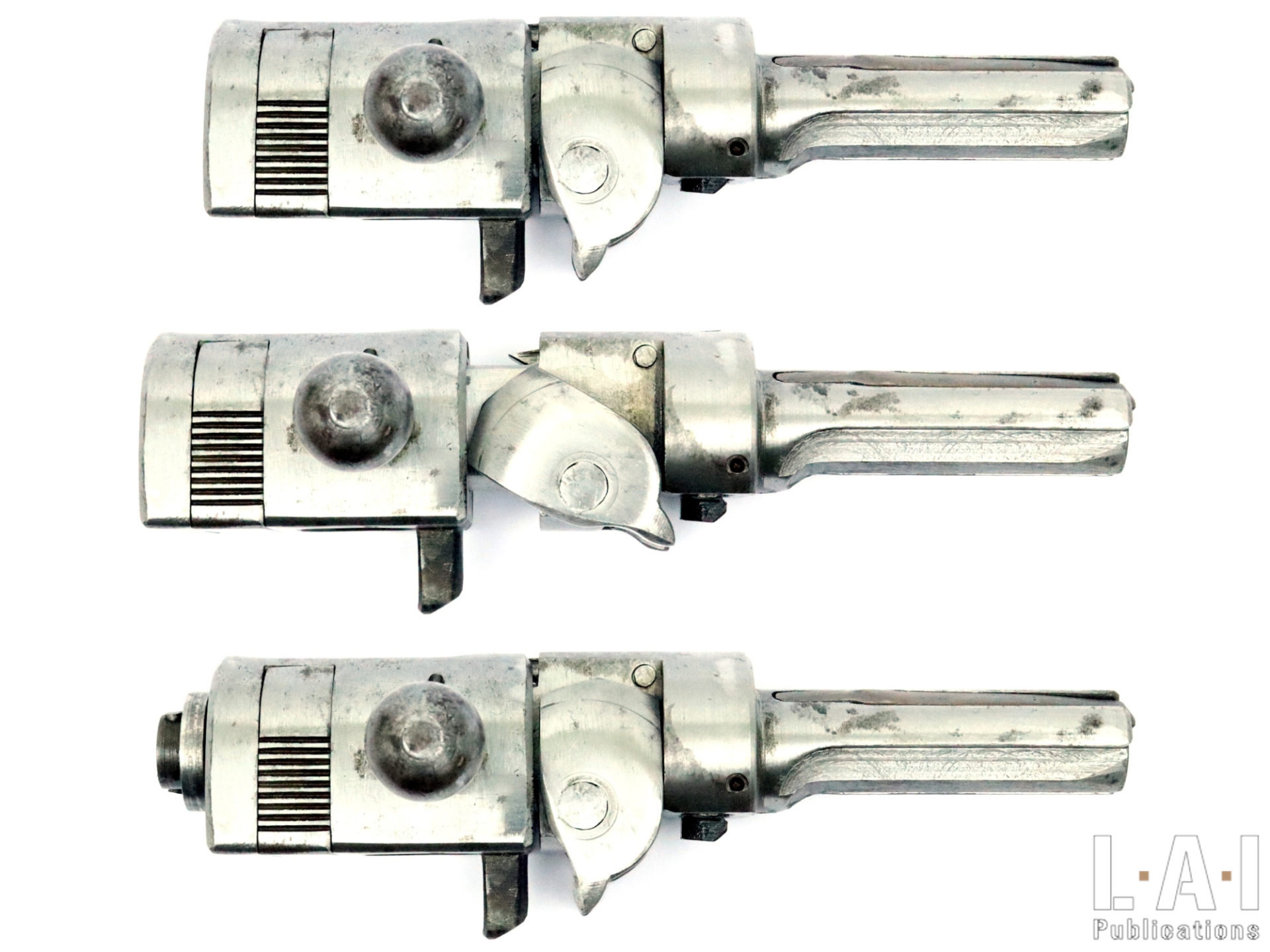

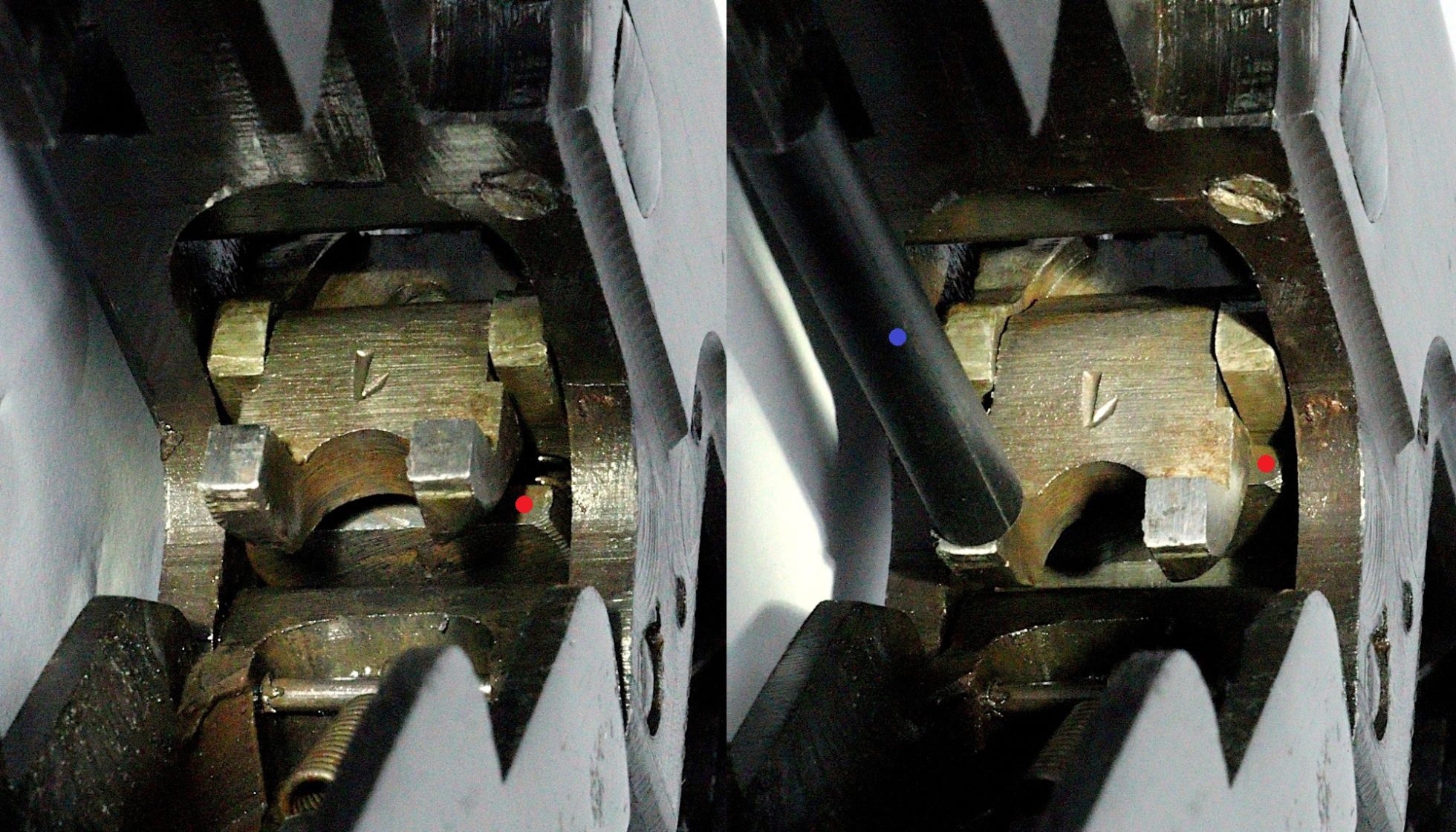

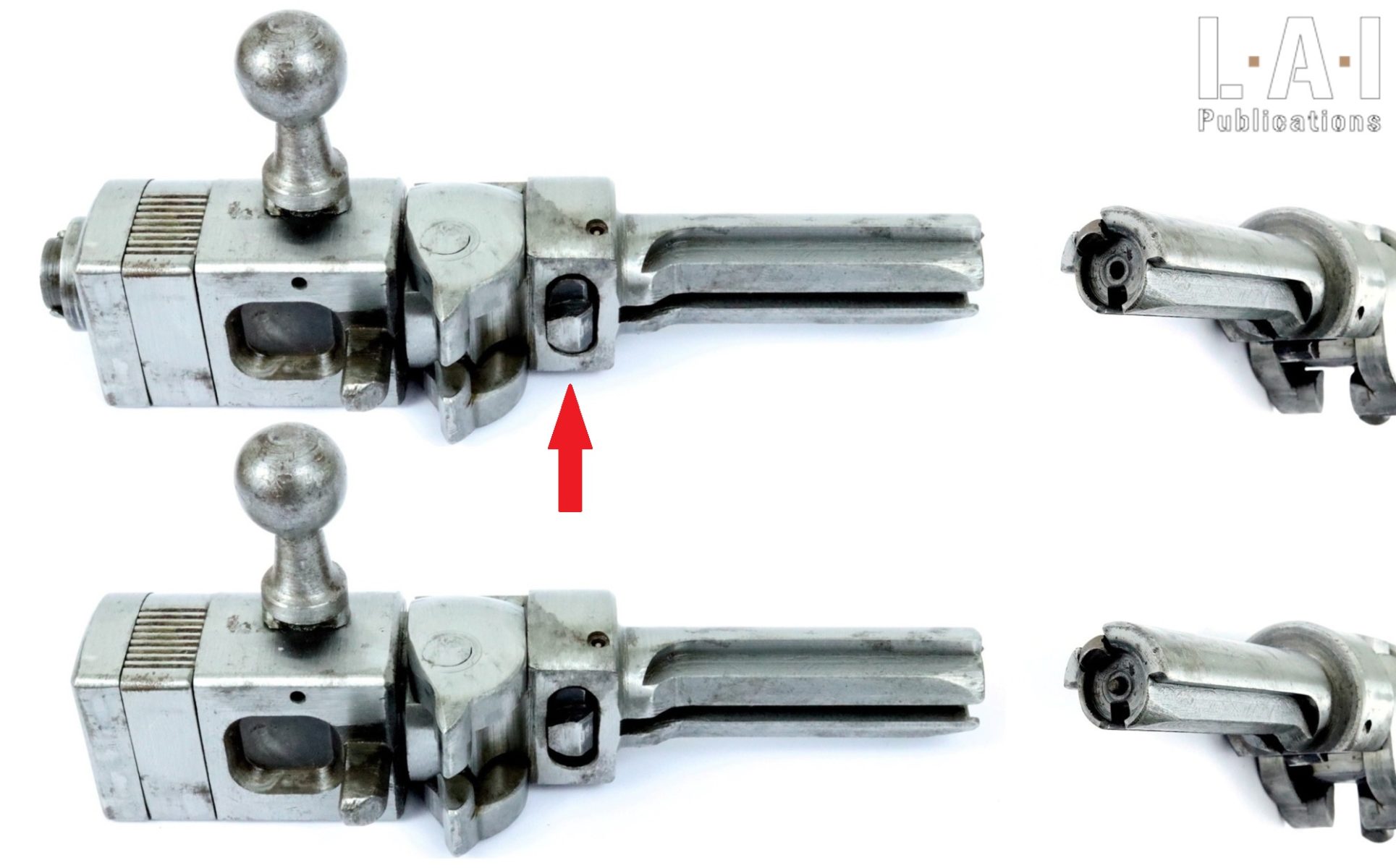

The weapon therefore operates from a mechanical advantaged blowback (often called “delay-blowback… cf. Chapter 6 of the Small Guide for Firearms for detailed explanations! ). Here, the device is an inertia amplifying lever, as on the weapons of Pál Király, or the French AA-52 and FAMAS of the post-war era. Let’s call this lever… “LAI” (TN: in French “Levier Amplifcateur d’Inertie”)! There is therefore a bolt, a lever composed of two independent arms on either side of the bolt and an additional mass which is amplified by the device (Pic.23). The lever is supported inside the receiver by a clearly rounded fulcrum. This arrangement obviously makes it possible to target precisely the place in the frame where very hard steel is needed (Pic.24). We note here that the markings of the FNAB-43 Type 1 wear the mention “Brevetto Scalori” (Scalori Patent): we have not found precise information on this subject, but it would not be surprising if it concerns this mechanical advantaged system, then only used (to our knowledge) by the weapons designed by the Hungarian engineer Pál Király. We can note here that contrary to many weapons that operate with a mechanical advantaged blowback system, the FNAB-43 chamber is not fluted.

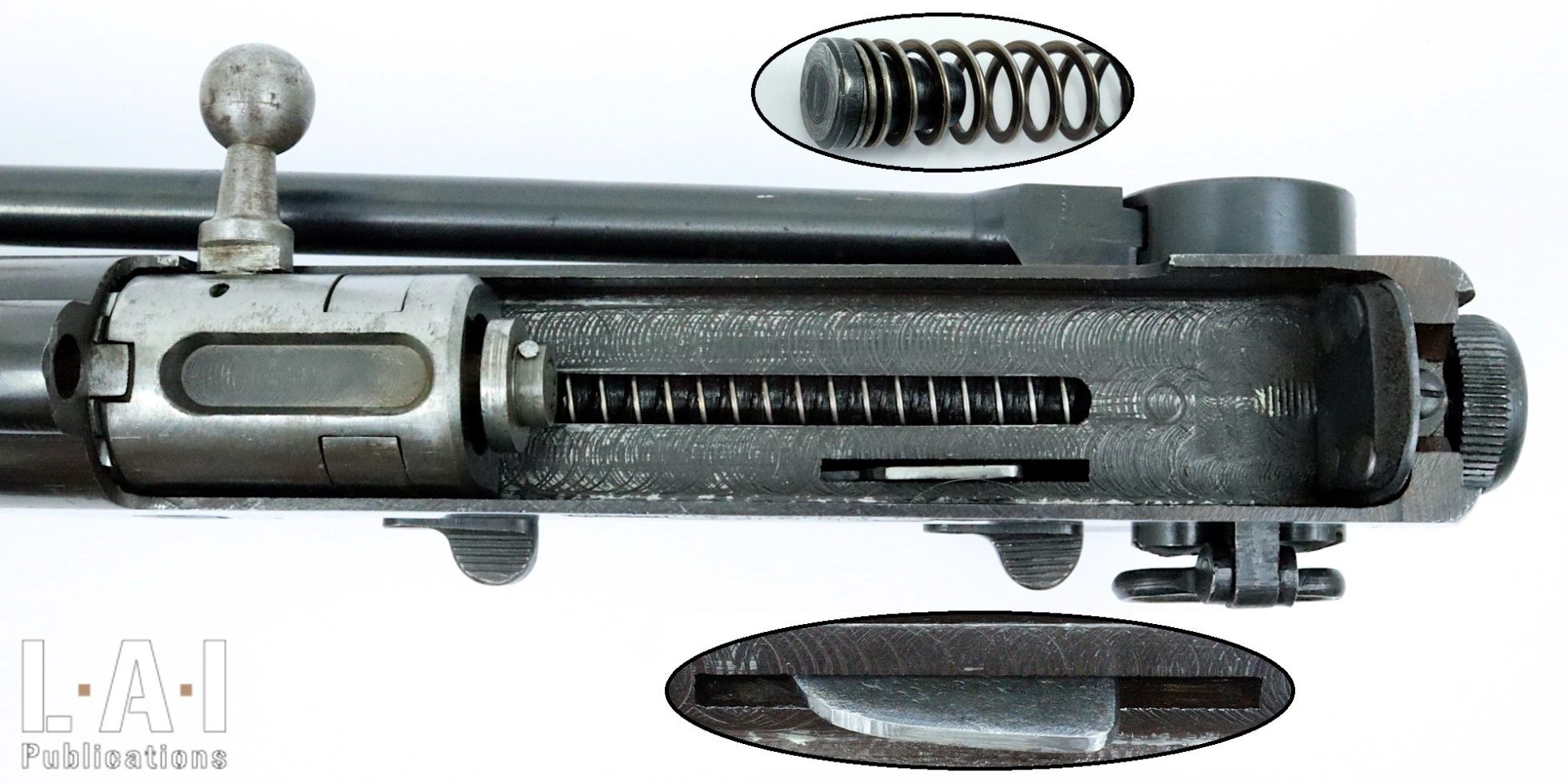

If the use of this particular system was new in Italy, it should be noted that the Villar Perosa and its descendants also employ an artifice (described in Mr. Heidler’s article on the same site) intended to “relieve” the bolt in order to reduce its mass. Because yes, that’s the goal here, to make a less heavy breech mechanism: 430 g only for the FNAB-43 BCG against 627 g for a STEN Mk.II bolt (with its cocking lever). That’s about 31.4% less for the FNAB-43 BCG… considerable! The counterpart of this system is usually an acceleration of the speed of movement of the BCG (the energy, does not magically disappear, it is transformed!) … and therefore, a generally high cycle-rate, especially in the absence of a rate reducing device. As on the MAB Mod.38 there is a recoil spring of small diameter, but this time captive of the receiver and not telescoped in the bolt (visible in Pic.11). It must be noted here that this spring is of a flat-wire type, and not of a round-wire type as most of the springs of that era! But let also remember here that this kind of spring, wildly used on contemporary weapons (especially on handguns), are known and used since the beginning of the 20th century (with the Roth-Krnka M.7 pistol for example!).

Here, information generally provided on the documentation concerning this weapon questions us: how, given its mechanics, can one think that the rate of fire would only be 400 rounds per minute? This is extremely low for an automatic weapon for those who would doubt about it… No rate-reducer, a “normal” breech stroke (a matter subject to debate, but it is not particularly long for a weapon of this type: about 100 mm when the STEN stroke is about 145 mm), a mechanical advantaged blowback, a powerful ammunition (the Italian 9 mm M.38) … All the ingredients of a high cyclic rate are normally there… And in fact, our measurements on the video sequence available in this article give 837 shots per minute! Yes, twice as much as the 400 rpm announced… One might think that the mystery lies precisely in the use of our test cartridge, probably weaker than a 9 mm M.38: it is possible that a more powerful ammunition will cause a larger (but also faster) recoil of the BCG and therefore, a slightly different cycle. This precaution being stated, let’s relativize: it seems unlikely that this simple fact could be at the origin of a division by two of the cyclic rate… Especially on our video, we see that the BCG is, most of the time, not far from the stop. No, reality seems, as often, simply to be the “parrot” effect: repeating information without analyzing or verifying it. Here, someone one day “claimed”, probably without ever having fired the weapon, that given the architecture of the beast, then the rate must be low… and everyone kept repeating that over and over again. Be careful not to judge too hastily (young hobbit), at times, we are all subject to this phenomenon if only for the technical data of the weapons that we do not have at hand … Also, my reading friend, take care to remain critical, including of our own work: make your own opinion! For our part, this pushes us, as far as possible, to measure and check everything times and times again. And of course, we are not immune to a mistake!

At the end of the rear stroke, the BCG encounters a buffer riveted on a sheet steel plate itself screwed to the receiver (Pic.25). Likely in leather, it reminds us of the PPS-43’s, but where it is attached to the recoil spring assembly. However, let us be careful not to draw any conclusions: we all see what we already know… Another cognitive bias! Always be careful! Moreover, the two weapons being extremely contemporary (both designed in 1942 for production in 1943), it is unlikely that the Soviet weapon influenced the Fascist weapon.

Unlike the other Italian SMGSubMachine Gun More of the period (and even, the majority of world SMGSubMachine Gun More pre-WWII), the weapon fires from a closed bolt, a plus for accuracy, because removing the “unbalance” of the bolt before the departure of the shot. We may find here a reminiscence of the concept of “Automatic Musketoon”, which favors a precise use of the weapon. And it doesn’t seem silly to us: the HK MP5, perhaps the most popular SMGSubMachine Gun More of the post-war period, also fires from a closed bolt and is praised, among other things, for it. The comparison with the MP5 will not stop there, but we will come back to it when we talk about shooting.

The firing itself is ensured by a spring-loaded striker contained in the BCG. Its cocking is carried out on the rear movement of the BCG: more precisely by the separation of the bolt and the additional mass (therefore by the action of the LAI – Pic.26). Its “commanded triggering” (i.e. when the trigger is pulled) is ensured by a “drawer sear” carried by the bolt and not by the additional mass: thus, the connection between the elements of the trigger mechanism and the bolt are not dependent on the complete closure of the BCG (Pics.27 to 31). This seemingly unsafe provision is subject to another device at the top of the BCG. It is a lever that locks the striker to the cocking position and as long as the additional mass does not come “in contact” with the bolt: it is the automatic sear (Pic.32). We put “in contact ” between quotation marks, because in the rules of the art, in an advantaged mechanical blowback system, the bolt and the additional mass must not be in direct contact during the shot: if this is the case, then part of the impulse of the shot is transmitted directly to the additional mass without passing through the device, which in fact “by-pass” the device. The automatic sear acts, as often, as a closing safety for the firing other than those conducted in burst. In this role, it has a major defect: once activated, a partial removal of the additional mass does not allow it to be reset. It is therefore possible to trigger a controlled shot with an additional mass in recess. What are the risks? In reality, they boil down to a percussion misfire: indeed, for the striker to protrude into the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More, the additional mass, which carries the striker’s nut, must be in the forward position. So, if the latter is at the rear when the shot is triggered, then the striker pulls the additional mass forward, but not without consuming some of the energy available for the percussion.

Finally, the weapon remains classic on an aspect that is still very important in terms of reliability: the extractor / ejector couple is quite common. The extractor is of the ” spring blade” type and the central ejector is attached to the receiver. Unlike the MAB Mod.38, the ejection is done on the right through a port in the receiver. It is also noted that the top of the ejector is shaped in order to direct the ejection (visible in Pic.35).

For cinematic sequences lovers only… others can move on to the next paragraph!

A loaded magazine is engaged, a cartridge is inside the barrel chamber and the BCG in the closed position with the firing mechanisms cocked. The safety is off, the selector on the “semi-automatic” position.

The shooter’s finger pulls the trigger. This pushes, through the transmission bar, the semi-automatic firing connector. The latter acts on the “sear pusher group”. Carried by the ejector’s base, this assembly consists of a lever lifting the actual pusher which is subject to two return springs. Thus operated, the sear pusher assembly raises the sear inside the bolt. The striker having previously been released from the automatic sear at closing, it is therefore free to fall on the primer.

The weapon is fired.

As the bullet moves inside the barrel, the cartridge case pushes the bolt that carries the LAI. The LAI is then in contact with the fulcrum of the receiver at the bottom and with the additional mass at the rear: to tilt backwards over the fulcrum, the LAI must push the additional mass. But the latter has its inertia (related to its mass) amplified by a ratio induced by the geometric arrangements of the LAI.

So instead of pushing the 430 g (267g of bolt + 163 g of additional mass and its key) physical mass of the BCG, it pushes a mass of:

267+ (163 x LAI Coef.)

The amplification coefficient of the LAI is not known to us in the case of FNAB-43, but if (and only if) we reason by analogy with FAMAS numbers in mind, whose lever amplifies by 3.6 times the inertia of the additional mass, then we would obtain:

267 + (163 x 3,6) = 853 g

We understand here the interest of the device. As an indication, to obtain an inertia equivalent to a STEN’s bolt (627 g), it would be enough to amplify by about 2.21 times. In return for this amplification, which slows down the bolt during the implementation of the LAI, the additional mass is “accelerated” compared to the bolt itself: therefore, in the end, the cycle rate is also amplified.

Add to this that during the implementation of the LAI, the striker is re-armed: another source of energy consumption. Finally, it should not be forgotten that part of the bolt’s movement (however small it may be) is transferred to the receiver via the fulcrum in the form of recoil.

Once the amplification has been carried out and the tilting of the LAI is completed, the BCG continues its stroke on its inertia.

The extractor holds the case head in the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More until it meets the ejector: it is then violently pushed through the ejection window by pivoting around the extractor.

The BCG continues its recoil on its inertia, compressing the recoil spring.

When the BCG moves backwards, it meets the rear end of the semi-automatic firing connector that protrudes into the receiver (visible in Pic.11). By pressing it, the connector rotates and is separated from the sear pusher group.

Depending on the power of the ammunition, the BCG finishes its course, either by consuming its energy by compressing the recoil spring, or by hitting the buffer attached to the receiver. The recoil spring then decompresses and returns the BCG forward.

On its forward movement, the bolt takes from one of the lips of the magazine, a fresh ammunition that it introduces into the chamber.

When the bolt finishes its forward stroke, the additional mass continues its course causing the LAI to tip over. At the end of the front stroke, the additional mass clears the automatic sear on the bolt.

The striker is then held by the main sear. To shoot again, it is therefore necessary to release the finger from the trigger to re-create the connection between the semi-automatic firing connector and the sear pusher group. The weapon performed a “semi-automatic” cycle.

For automatic firing, the sequence is close, except that the automatic fire connector is tilted by the selector to make contact with the sear pusher group. Unlike the semi-automatic firing connector (positioned on the left), the automatic firing connector (positioned on the right) does not protrude into the receiver and is therefore not disengaged by the course of the BCG. It is therefore not “disconnected” at each cycle. Thus, as long as the shooter’s finger pulls the trigger (and as long as there are cartridges in the magazine), the operation of the automatic sear at each closure triggers a shot.

Note that the selector has no action on the semi-automatic fire connector: when the burst fire is triggered, this connector works normally and is found, after the first cycle, disconnected for the rest of the burst.

The safety, meanwhile, permanently disengages the two connectors while inserting itself into a housing of the automatic fire connector: thus, the action of the trigger is no longer possible (it is immobilized) and the connectors are no longer in contact with the sear pusher group.

Versions and markings

As is often the case for weapons produced in small quantities, the information available is ultimately scarce. And quickly subject to fantasies! The identification markings of Type 1 are on the left side of the receiver (Pic.33):

Pist. Mitr. FNA Brescia Mod.43

Brevetto Scalori

N. 0000

“N. 0000” obviously refers to the location of the serial number which is composed of 4 digits. The markings of the fire selector display “Raffica” (burst) and “Colpo” (1 shot). The markings of the safety: “S” at the top, and “F” at the bottom.

The identification (re)markings of Type 2 are in the same place but affixed in a shallow coarse milling obviously subsequent to the manufacture of the weapon (Pic.34):

MASCHINE-PISTOLE P.M.43

Cal. 9mm

In addition to this rudimentary but clean re-marking, the markings on firing selector are erased by milling. The safety markings are unchanged.

This is the third copy that we have had the opportunity to examine in person, and the first in firing condition that we can examine in detail. All were Type 2 weapons. The pictures of the Type 1 available in this article were graciously provided to us by the IRCGN, but we did not have one in hand… For the moment! It is noted that below the re-marking of Type 2, where once stood (perhaps?) the serial number affixed to the manufacture, the marking has been “scratched”: a curious detail that appears on all the copies of the Type 2 examined (in person or on pictures) and not re-blued or re-phosphated! Some sources claim that the serials number has previously been re-weld. It is possible, but the thing seems unlikely to us on examination: no trace of heating on any side, no variation in the nature of the metal and in case of re-treatment (some copies seen have been re-blued and even re-phosphated), no nuance in the color. Moreover, one may wonder if this practice (from the premise point of view, not the technique one) is not anachronistic…

We can wonder here about the nature of this re-marking… and, finally, on the very nature of the production of FNAB-43 Type 2. The marking mixes “pseudo-German” (“Maschine-Pistole”, where “Maschinenpistole” should be written) and Italian (P.M. or Pistola Mitragliatrice), while specifying the caliber of the weapon (but with “Cal.” and not “Kal.” as sometimes encountered on weapons destined for Germany), things that do not appear on the original marking. Two hypotheses can be considered here:

- A bad “Germanization” of the production of the weapon, made in very particular circumstances of a time when Italy had just fallen under German control, on a slightly simplified production already in stock, but not distributed… and perhaps a number of weapons ultimately low. It can be noted that this would not be the only “Germanization” of marking: VIS-35, CZ-27 and others FEMARU M37 remind us, among other things, that it was a common practice of the 3rd Reich in occupied areas … which was indeed the case of Italy during this period!

- A makeup made after the war on a small stock remaining, or on a “new production” (perhaps a simple assembly of spare parts) carried out to feed a weapons traffic… And therefore, organized crime, terrorism, or guerrillas.

This second hypothesis really questions us: in this case, we cannot understand its purpose! Especially since the name of the weapon “P.M. 43” is very present… Which for a makeup, seems very stupid! Similarly, even if it means making up the weapon, why not re-machine the serial number at the same time?

The German misspelling probably comes from a simple lack of knowledge of the language. Whether the fruit of an Italian worker in very critical circumstances or that of a trafficker… Everyone will form an opinion. For our part, not being able to decide without more elements: both seem possible to us.

As for the “makeup” of the serial number, this one is more disturbing, because it seems posterior to the first modification and much messier. However, this one is recurrent on several weapons observed in different places: therefore, it had to be carried out by an organized structure with a certain number of weapons… difficult, if not impossible, to know which one.

As for the claim that all of this makeup is specifically intended to equip the FLN during the Algerian war… make your own idea, but personally, we do not quite understand the purpose of this operation, which would be specific to FNAB-43, when so many other weapons would be shipped to the FLN without this luxury of precautions, including Luxembourg Sola Super SMGs then freshly produced. Of course, we do not question the use of FNAB-43 by the FLN: the weapons supply scheme is always the same! A new conflict zone always absorbs the available weapons from a previous conflict… there is no reason why the Algerian war should be an exception! And that’s not about to change…

Finally, the fact that the majority of specimens encountered, in France, are Type 2 questions. Is it a trophy brought back from Algeria or have these weapons never left the continent? Then again, the mystery remains…

It is noted that in the two marking variants encountered, the concept of “Pistola Mitragliatrice” (“Pist. Mitr. ” on Type 1 or “P.M.” on Type 2) took precedence over that of “Moschetto Automatico”. And indeed, this weapon no longer has any reason to be called “Automatic Musketoon”: it has definitively moved away from the canons of MAB Mod. 1918 and MAB Mod.38 to adopt those of a contemporary SMGSubMachine Gun More.

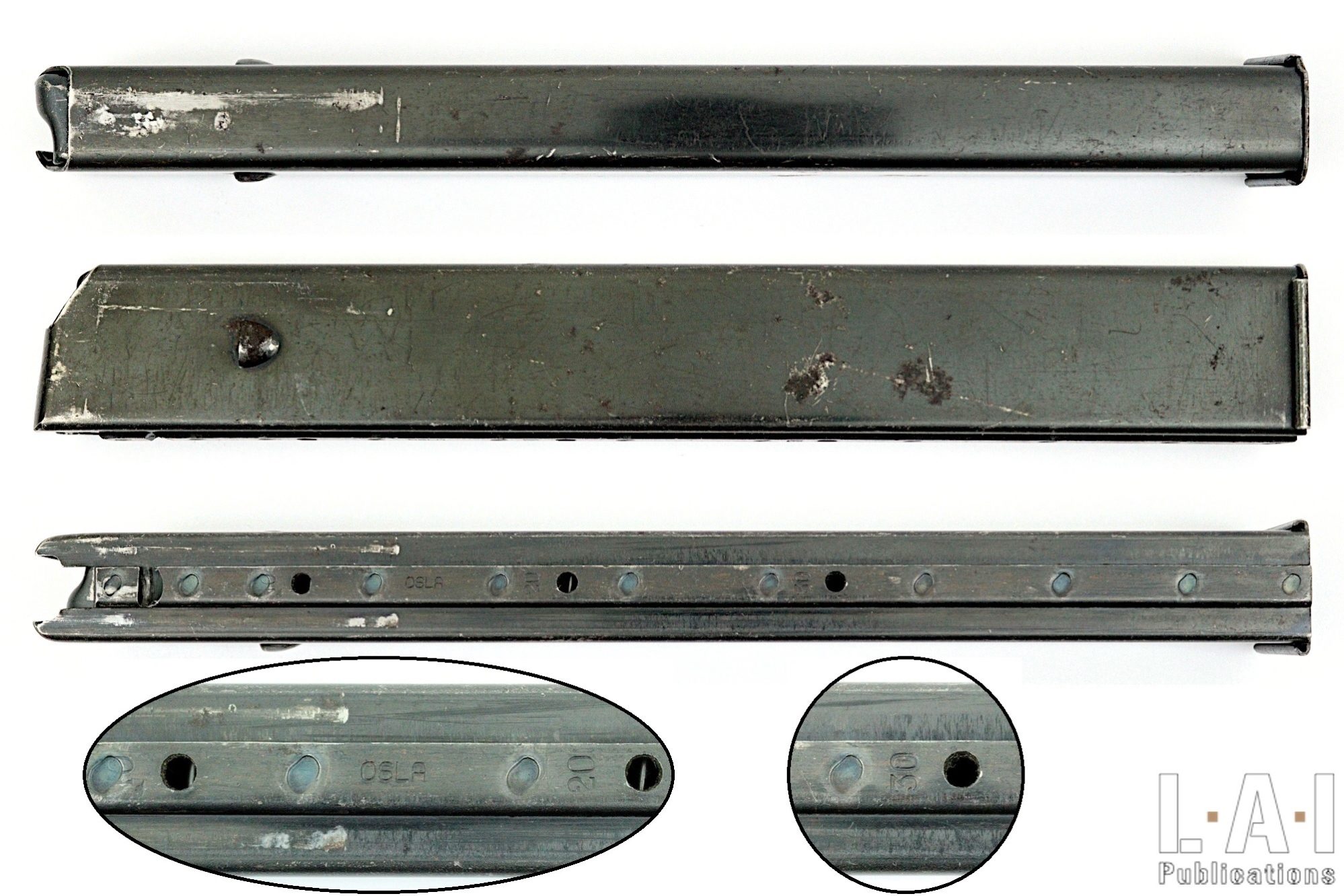

We are not in the habit of showing or talking about serial numbers, the thing is often irrelevant… but here we are facing a very special case with the Type 2 at our disposal. Many parts, including the receiver, barrel shroud, magazine well and pistol grip bear only one number: “1”. These parts should normally bear the last two digits of the serial number. Be careful, we do not pretend that the weapon could be the weapon “number 1″! The thing seems to us unverifiable and unlikely, especially because it is a Type 2 weapon, and its serial number seems to have been erased. We simply note that there are no other numbers visible on these parts and that this visible number seems to fit those affixed to the manufacture of the weapon and in no way a makeup. Other numbers are visible on some parts. Given the particularity of the number “1” previously stated, we will detail all the numbers encountered on the weapon (Pics.35 to 40 in addition to the numbers already seen on other pictures of Type 2):

- Receiver, right side, visible after disassembling the pistol grip: “1”

- Pistol grip, underside of grip: “1”

- Magazine well, front side: “1”

- Barrel shroud, rear end, on bottom: “1”

- Ejector, in magazine well: “1”

- Receiver cover, inner side: “1”

- Trigger: “1”

- Trigger transmission bar: “1”

- Semi-automatic fire connector: “1”

- Automatic fire connector: “1”

- Sear pusher lever: “1”

- Sear pusher: “1”

- Grips, penciled on the inner faces: “1”

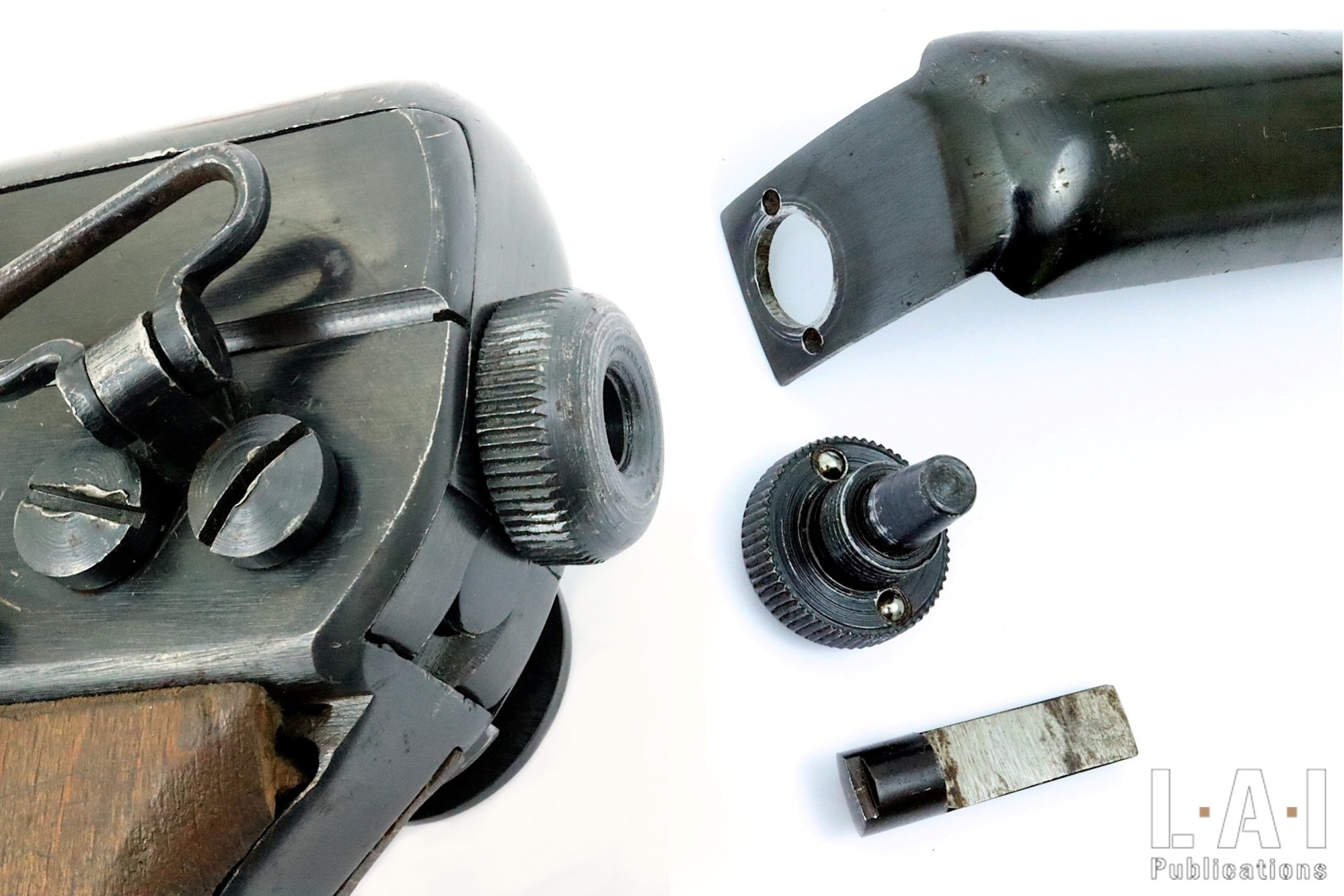

- Additional mass, rear side: “32”

- Additional mass key: “32”

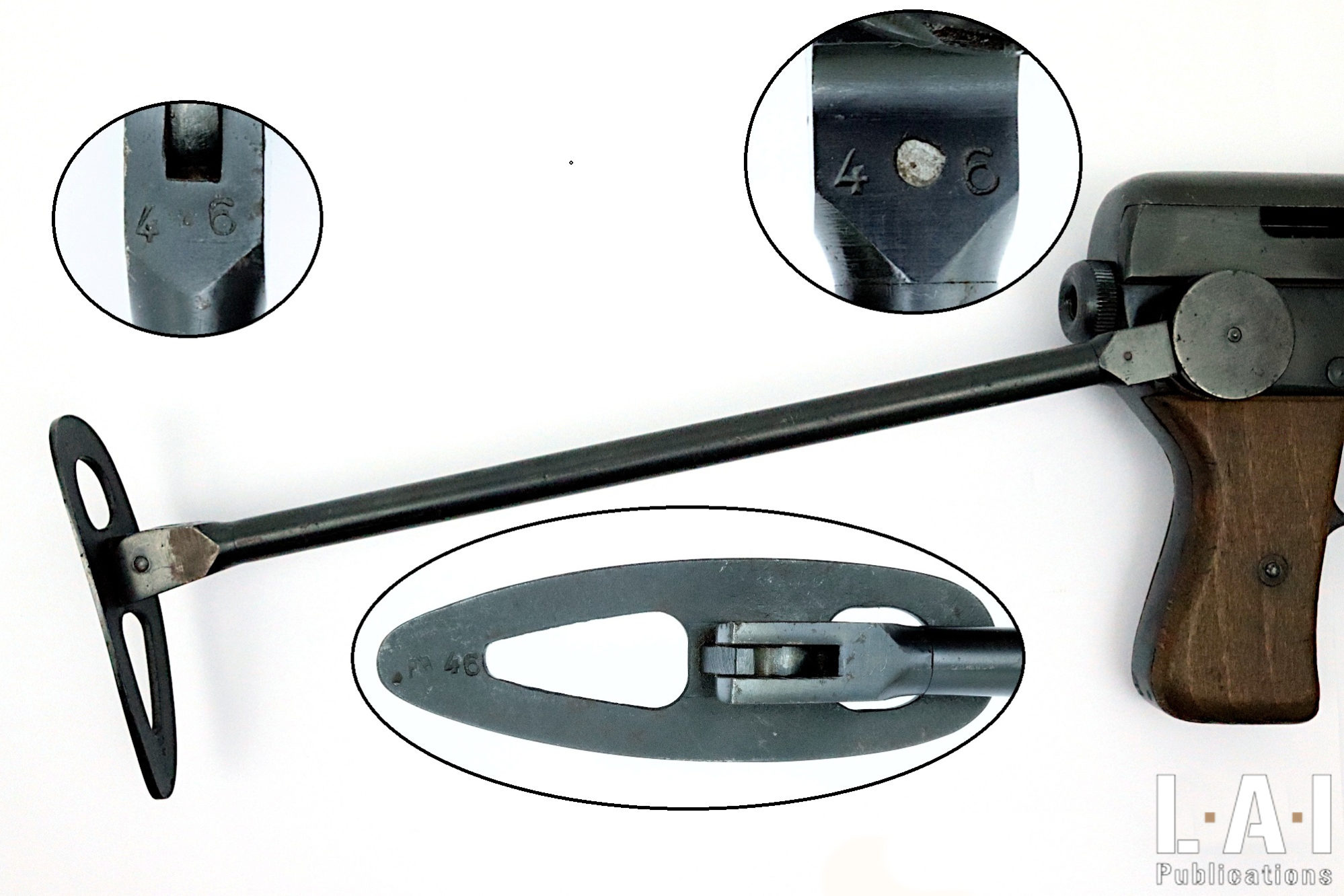

- Stock pivot: “46”

- Butt plate pivot: “46”

- Butt plate: “46”

What to make of all this? We confess to be puzzled… But it would seem that we are dealing with a weapon whose serial number is or contains as the last digit “1” and whose stock has been replaced by (or assembled at the factory with) the stock of a weapon whose serial number ends in”46″ and for which at least the additional mass and its key have been replaced (or assembled at the factory with) by those of a weapon whose serial number ends by 32. I will not draw any further conclusions, especially for a Type 2 weapon whose origins are anything but certain. In the absence of adequate documentation, we feel this would seem presumptuous.

Shooting

The grip of the weapon is “normal” for its category, that is to say a SMGSubMachine Gun More with folding wired stock and without a real handguard. It is at this moment that we regret a bulky wooden stock… However, nothing prohibitive, especially for a weapon whose recoil can be described without hesitation as “weak” or even “insignificant”. The shooter’s head therefore finds no support and the off-hand has, certainly, a grip on the magazine well, but it is not the most comfortable… In short, it is a weapon of war. The sights are well drawn, but clearly not to our taste: the shapes of the notch (V-shaped) and front sight blade (thick) are not our favorite, preferring the “U” sight notches with thin front sight blade (Pic.41). Taste and colors…! We will describe the trigger release as “sliding”, but a “failed” one: it does not oppose real hard points, but scratches irregularly on its stroke. A “sliding” and “successful” release is made without hard points, lengthy and without scratches. But here too, nothing prohibitive, it is a weapon of war.

At 100 m, the SC-2 French service target (a kneeling figure) is easily reached a 100% of the time, although we have to make a considerable aim leading: we have to aim at the target base and one target on the left! There too, we read, here and there, that the accuracy of the weapon would not be at the rendezvous: very clearly the FNAB-43 we shot is consistent with the majority of SMGSubMachine Gun More of this period that we tried. The burst shooting is obviously totally controllable, but once again a SMGSubMachine Gun More of about 3 kg in 9×19 that is not controllable would be a prodigy! The weapon is particularly stable: the choice of LAI has probably something to do with it, the moving mass being relatively low. The muzzle device, of course, also has a positive influence from this point of view. The following video will give you an idea.

While shooting, the surprise comes from a comparison that immediately came to mind: we have the impression of shooting with an MP5: the cyclic rate is fast, the low recoil finally very linear (despite an unfavorable stock slope, but probably compensated by the muzzle device). We point out that we subsequently read comparisons between the two weapons, comparisons which we did not known about during the test. But these comparisons were about technical choices and not about shooting. From our point of view, the comparison is based on the sensation of firing and for certain technical choices: both weapons fire with closed breech and use mechanical advantaged blowback, rollers on the MP5 and lever on the FNAB-43. On the other hand, it is completely unreasonable from an industrial point of view, again, something we have read! The FNAB-43 may meet circumstantial production requirements, but it cannot, at any moment, be considered a weapon of mass production. The MP5, on the other hand, is clearly a weapon of mass production!

Finally, regarding shooting, keep in mind that our tests were carried out with modern ammunition of 8 grams (124 grains) and not with 9 mm M.38 probably used in the design of the weapon. There must certainly be a difference, but this difference, although it exists, would not change things that much at all.

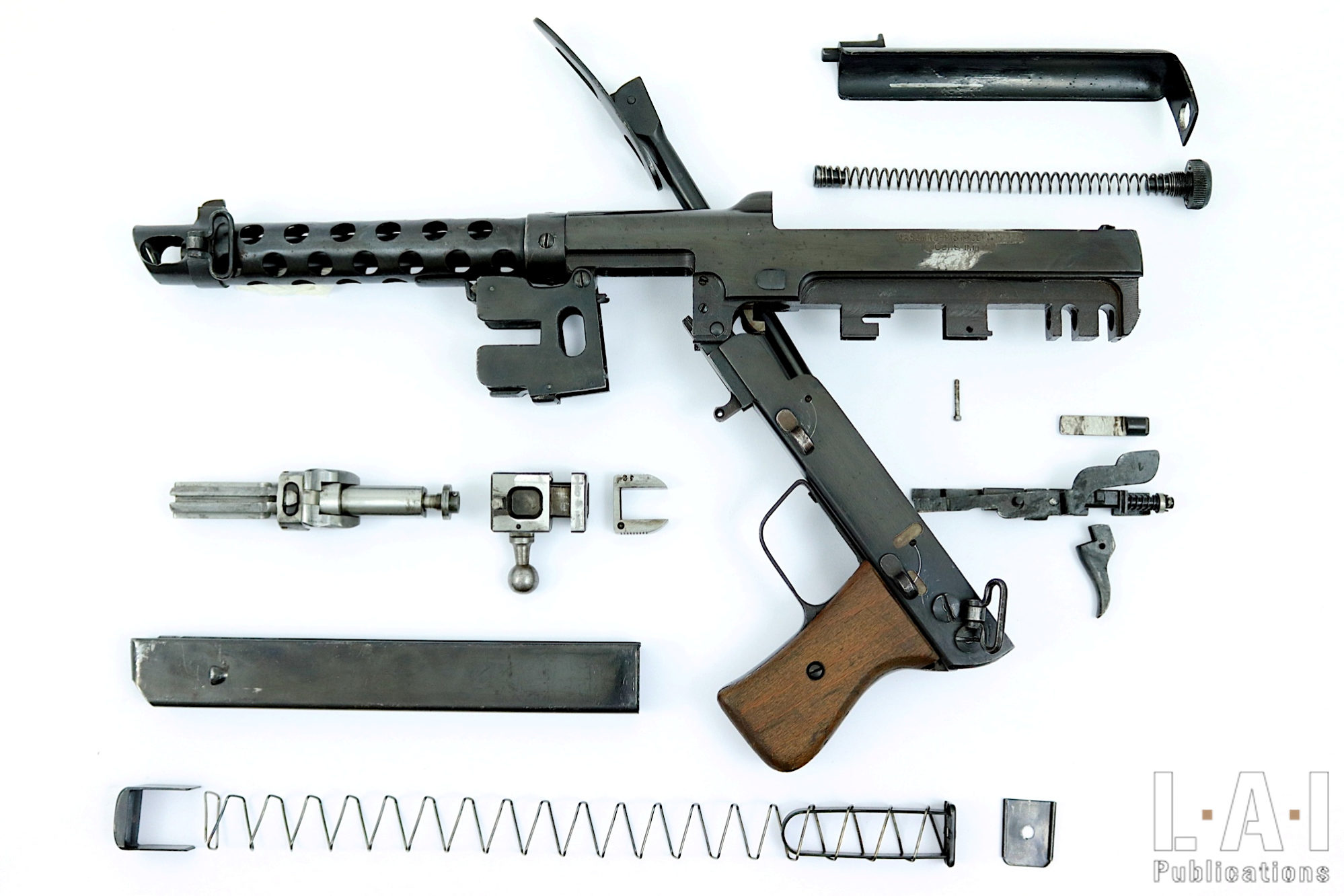

Disassembly and maintenance

Here again, the weapon is necessarily at odds with Beretta weapons, and for good reason, the receiver is no longer cylindrical. Disassembling is nevertheless simple (as seen on the video below). After having carried out the safety checks (no ammunition, neither in the weapon nor in the magazines concerned by the disassembly or present on the working surface):

- Remove the magazine from the weapon.

- Tilt the magazine well forward (the thing will be necessary later, we’d rather do it when the weapon is “simple” to handle…)

- Unscrew the assembly screw on the back of the receiver (it is knurled to be easily handled – Pic.42).

- Remove the screw: it comes with the recoil spring and its pusher.

- Remove the receiver cover towards the rear.

- Pull the BCG back and remove it from the receiver (we will complete its disassembly afterwards).

- Remove the assembly key from the pistol grip. To do this, you have to insert a tool (a 6.5×52 Carcano case does the trick!) in the notch provided for this purpose and lever it.

- Tilt the pistol grip (this is only possible if the magazine well is folded forward).

- Remove the trigger pin (you can do it manually on our copy).

- Remove the trigger group towards the back: be careful, the trigger is simply pushed on the transmission bar: it therefore easily leaves its housing … but also recovers as easily… if you previously paid enough attention to its positioning.

Disassembling of the BCG continues as follows:

- Remove the additional mass assembly key down.

- Remove the additional mass backwards.

Disassembling of the magazine(s) is carried out as follows:

- Using a suitable tool, push the locking plate inside the magazine and keep it in this position.

- Move the magazine floor plate forward: when it is sufficiently advanced for the locking plate not to re-engage in its orifice, remove the tool used to disengage the floor plate.

- While opposing the thumb to the outlet of the magazine (to avoid ejection of the spring and other parts), remove the floor plate.

- Remove the magazine spring and locking plate that is attached to the spring.

- Slide the follower out of the magazine (if it doesn’t come along with the spring).

Disassembly is really easy and reassembly, which is done in reverse, does not present any difficulty (Pic.43).

Accessibility for cleaning is generally good: only the area around the sear pusher group and the ejector is not easy to access, and we have known much worse! Compared to cleaning a cylindrical receiver weapon, the operations are simpler. A small personal opinion: we hate the presence of hinged mounted elements on a disassembled weapon (pistol grip of the Stg 44, receiver cover of the AKS-74u …). It is a real “finger eater” that never fails to close during cleaning operations that require positioning the parts in all directions… And here the pistol grip is no exception!

To conclude

The FNAB-43 is a curious weapon: at the time of its production, it seemed both very modern on its technical choices and archaic on its manufacturing methods. Announced as having been manufactured in about 5000 or 7000 copies, the “Mitra Zerbino” (nickname attributed to the weapon and derived from the name of the Minister of the Interior of the ISR) experienced the fighting of WWII, but also the terrorist actions and guerrillas of the Cold War. Thus, two FNAB-43s were used by members of the Red Brigades for the kidnapping of Italian politician Aldo Moro. A kidnapping that would end, in addition to the death of his 5 bodyguards, by his execution. Far from any morality, we are given the opportunity to remember that between the manufacture of a weapon and the use that is made of it, the ideologies motivating each of these acts are sometimes utterly different … food for thoughts (Pic.44).

Arnaud Lamothe

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!

Thanks:

Gilles Sigro-Peyrousère (Atelier Saint-Étienne) for the supply of the weapon, his advice and proofreading.

Luc Guillou, for his articles in “La Gazette des Armes” N°283 and N°409, for his advice and proofreading.

The Ballistic Department of the Criminal Research Institute of the National Gendarmerie (IRCGN – Institut de Recherche Criminelle de la Gendarmerie Nationale) for the pictures of the FNAB-43 Type 1.