The end of WWII was the twilight of a multipolar world and the dawn of the Cold War era. A tipping moment that opened up to the unknown. Many things had to be rebuilt, but also many concepts, had to be thought anew. Although this may seem ridiculous in the face of history, this is what the Soviets did for their handguns and its caliber: rethink the concept for defensive use. From this reflection, a service weapon would be born, particularly atypical in its context: the Makarov pistol in caliber 9×18 mm.

A new caliber

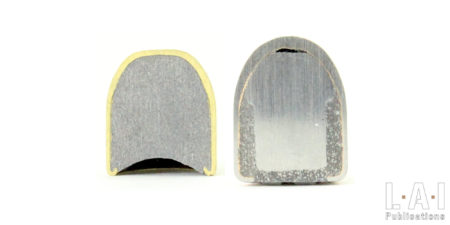

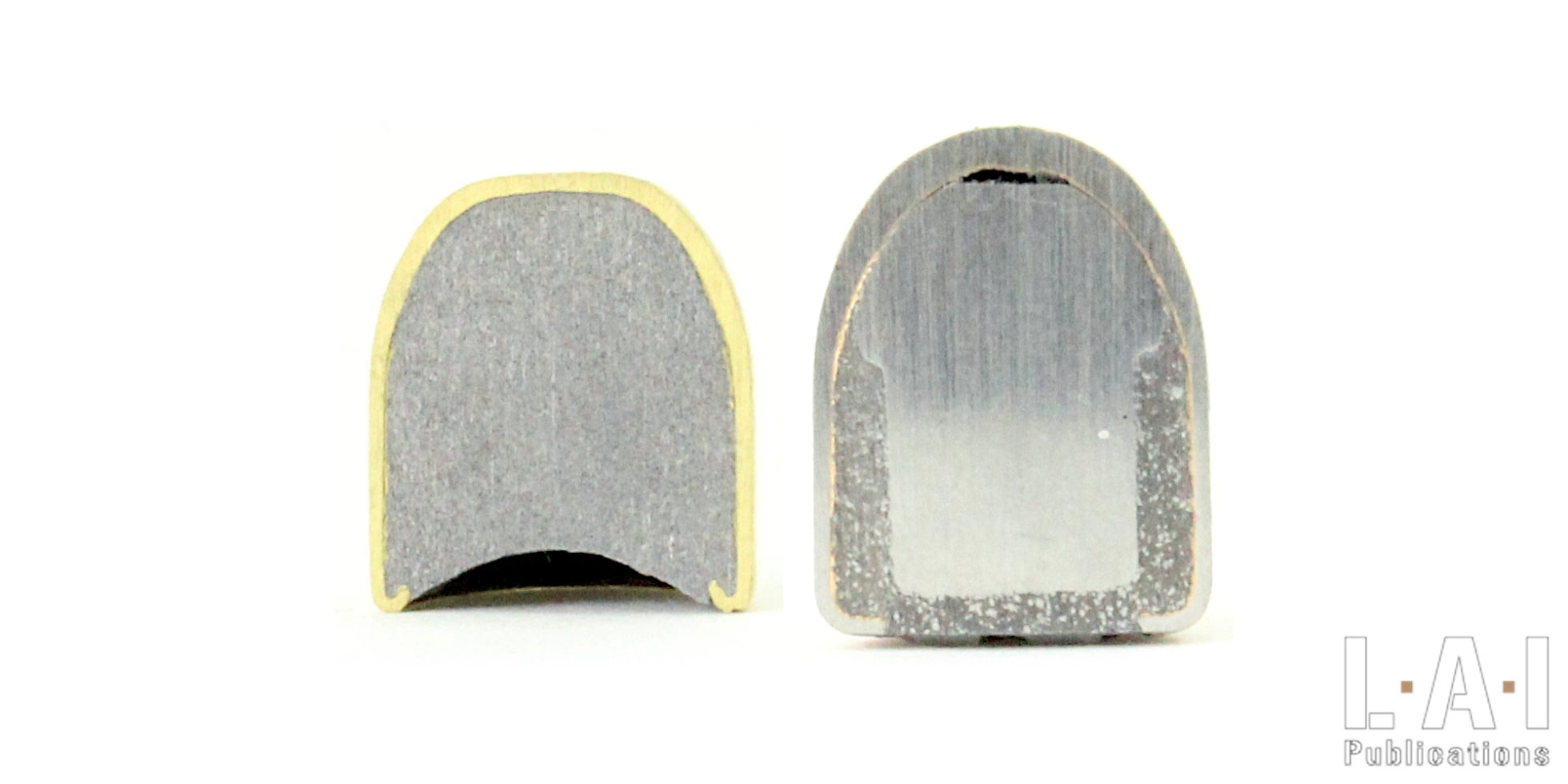

The 9×18 mm caliber “Makarov” was probably finalized between 1947 and 1948 by Boris Semin, one of the fathers of the 7.62×39 M43. The original ammunition featured a cylindro-spherical with a flat-base bullet with a lead core, copper-plated steel jacketed for a weight of 6.2 grams. This bullet would quickly be replaced by a bullet of a same shape but with a mild-steel core (mushroom-shaped) coated with lead and copper-plated steel jacketed for a weight of 5.75 grams (Pics.06 and 07). The cases would first be made out of brass, then copper-plated steel or lacquered steel. This evolution consisting in generalizing the use of steel, which is found on the majority of Soviet ammunition, responds above all to the desire to save expensive and strategic materials: lead and copper. Regarding the bullet, the presence of a mild-steel core also increases the perforation capabilities under certain circumstances. However, a mild-steel core is not an “armor-piercing” core: it is an “ordinary” bullet in terms of its perforation capabilities. Concerning this last point, this point of view is a technical one, not a legal one: dura lex, sed lex. The muzzle velocity of the service ammunition is announced in the official documentation at 315 m/s when fired in a Makarov pistol and at 340 m/s (thus slightly supersonic) fired in a Stechkin pistol.

According to the expression then consecrated by the Soviet authors D.N. Bolotin, the 9×18 “Makarov” was to replace the 7.62×25 while retaining “the striking power of their 7.62 mm predecessor“. The thing seems obscure, the two munitions are simply not comparable… The 7.62×25 is more than twice as powerful as the 9×18 in terms of kinetic energy, from 0 to 50 m. The very notion of “striking power” (sometime also called “stopping power”) is not a very scientific notion, subject to fantasy but which could be the subject of an interesting debate… which we will not start here! The terminal effectiveness of an ammunition is a complex thing, difficult to address quickly and which would not be reduced to a simple comparison of kinetic energy. The speed at which this energy is delivered to the target (the nature of which is to be defined) is an important factor to take into account, as are the desires in terms of perforation. In short, a complete specification is needed to qualify what the “customer” expects from an ammunition. And expectations can vary greatly from one “customer” to another, if only between those of a Police Officer and a Soldier! Concerning the Makarov, it is necessary to be pragmatic: it is an ammunition intended for handguns whose vocation is limited to personal defense at close range at a time when individual ballistic protections were still very rare. It can be noted, however, that in the USSR, the end of WWII had democratized the wearing of the “Stalnoi Nagrudnik” (Стальной нагрудник) steel plates, a ballistic protection, which can be qualified as “cuirass”, whose technical characteristics are however quite far from our current “Bullet-proof vest”. Thus, in this role and in its context, the 9×18 Makarov is excellent: it is powerful enough to put a man out of action effectively and sober enough not to require the design of a weapon too complicated that need a locking mechanism or able to generate by its power breakage of parts as was (presumably) the case with the 7.62×25 in the TT 33. Regarding wound ballistics, an interesting choice deserves to be highlighted here: the bullet is not “cylindro-ogival”, but “cylindro-spherical” (difference visible on Pic.06). This choice has two consequences: for the same bullet length, its mass is increased (in a small way certainly, but in ballistics, every gain counts) and the bullet has a less aerodynamic shape than most other contemporary handguns (and in particular, the 9×19 or the 7.62×25). This last point, which can be considered as a disadvantage in terms of external ballistics, is clearly an advantage in terms of wound ballistics. It is thus quicker to slow down quickly in the target and to transfer its energy faster… while respecting the Hague Conventions, because they do not undergo any expansion! Thus, while being less powerful and less piercing than a 7.62×25, it is probably more lethal with its spherical 9 mm. On the other hand, in view of pure penetration (understand here, in a layer protecting the target), the 9×18 Makarov can certainly not claim to compete with the 7.62×25 Tokarev… But is this “anti-materiel” purpose really devolved to a handgun ammunition? Once again, this question can only be resolved by drawing up proper specifications!

The 9×18 Makarov would be put into service through two weapons in the USSR during the Cold War: the Makarov pistol and the Stechkin “APS” machine pistol. We will deal through this article only with the Makarov, the Stechkin being treated in an article to be published in two weeks … Stay tuned. It would know other uses within the Warsaw Pact in some rare pistols and SMGs, as well as sporadic uses in other weapons of post-Soviet Russia… some of which will be featured in this collection of articles!

Several types of ammunition would be produced, including hollow-point (presumably for law-enforcement purpose), armor-piercing and even tracer ammunition. The ammunition even experienced a significant production among manufacturers outside the USSR. Note also here the appearance in the early 1990s of a “modernized” ammunition called “9×18 PMM” in dedicated publications. This ammunition would display performance comparable to the 9×19 Parabellum (a claim subject to caution) with a muzzle velocity of the order of 415 m/s fired in the “Modernized Makarov Pistol” that we will discuss later. Its use is reserved for this “Modernized Makarov Pistol” sometimes called “second generation” and some submachine guns of post-Soviet Russia. Warning: the use of this ammunition in another weapon (including the Makarov “PM” and Stechkin “APS” pistols) can lead to a rapid deterioration of these. Once again, each weapon is designed for a specific range of ammunition and not necessarily for all existing ammunition for the same caliber.

A handgun for universal defensive use

In 1945, the USSR launched a competition where Nikolay Fedorovich Makarov, designer at the Tula design bureau (KBP) and other designers of the Soviet Union (including Tokarev, Simonov, Korovin, to name only the best known by Soviet weapons enthusiasts) were called upon to design the replacement of the TT 33. The new pistol had to be more compact, lighter, more accurate (a notion that likely include the “hit probabilities” ones in the mind of the Soviets) and more reliable than the TT 33. The caliber was to be 7.62×25 or 9×18, a caliber then in development: the choice being left to the discretion of the designer. The weapon would be particularly severely judged on questions of reliability, a well-justified obsession for a weapon of war and very present in the Soviet military mind. In 1951, N.F. Makarov’s weapon was adopted in caliber 9×18 mm, although the designer also proposed a weapon in 7.62×25. Its official name is “9mm Pistolet Makarova” (Пистоле́т Мака́рова), often abbreviated to “PM”. This new weapon, of a size close to a pocket pistol, was intended for a “universal” endowment for the armed forces and police of the USSR.

Often considered as a pure and simple clone of the Walther PP (which dates from 1929 – Pic.08), the Makarov shares with it mainly much of its ergonomics, but ultimately only a little of its mechanics. We will clarify these similarities and differences as the weapon is described. It cannot be denied, however, that the Soviets were influenced by the German weapon: they knew it well! It seems it was one of the myriads of pocket pistols purchased before WWII (TK-26 production having ceased in the mid-1930s) and it was probably seized in significant quantities during the same conflict.

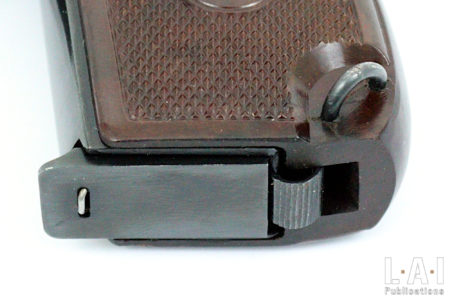

From an ergonomic point of view (not to mention disassembly, which would be described later), we are in the presence of a semi-automatic pistol featuring a single and double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More firing system and safety/decoking lever positioned on the left side of the rear part of the slide (Pic.09). First difference, the safety lever is operated in the reverse of the German weapon’s: at the bottom, it is ready for firing, at the top, the safety is on. This choice probably comes from the feedback of the PP (but also perhaps from Makarov’s pre-series, the design of the lever having evolved): when cocking the slide, one tends to disengage safety and not to engage it. Users of MAC 50, Beretta 92 (and its variants) and of course the Walther PP will easily understand the point here. The thing is particularly obvious with the MAC 50, to the point of becoming a defect under our current criteria: when cocking the slide, one naturally tends to engage safety. And the thing seems to have been thought that way on the MAC 50! Legend even has it that at the adoption of the MAS G1 (variant of the Beretta 92 in service within the French Army, Gendarmerie included), the choice not to have a safety, but only a decoking lever was partly influenced by this “feedback” from MAC 50. On the Makarov, it is the opposite: there is a tendency to disengage the safety on the same movement as the cocking of the slide. And in fact, to be able to cock the weapon, the safety must be off.

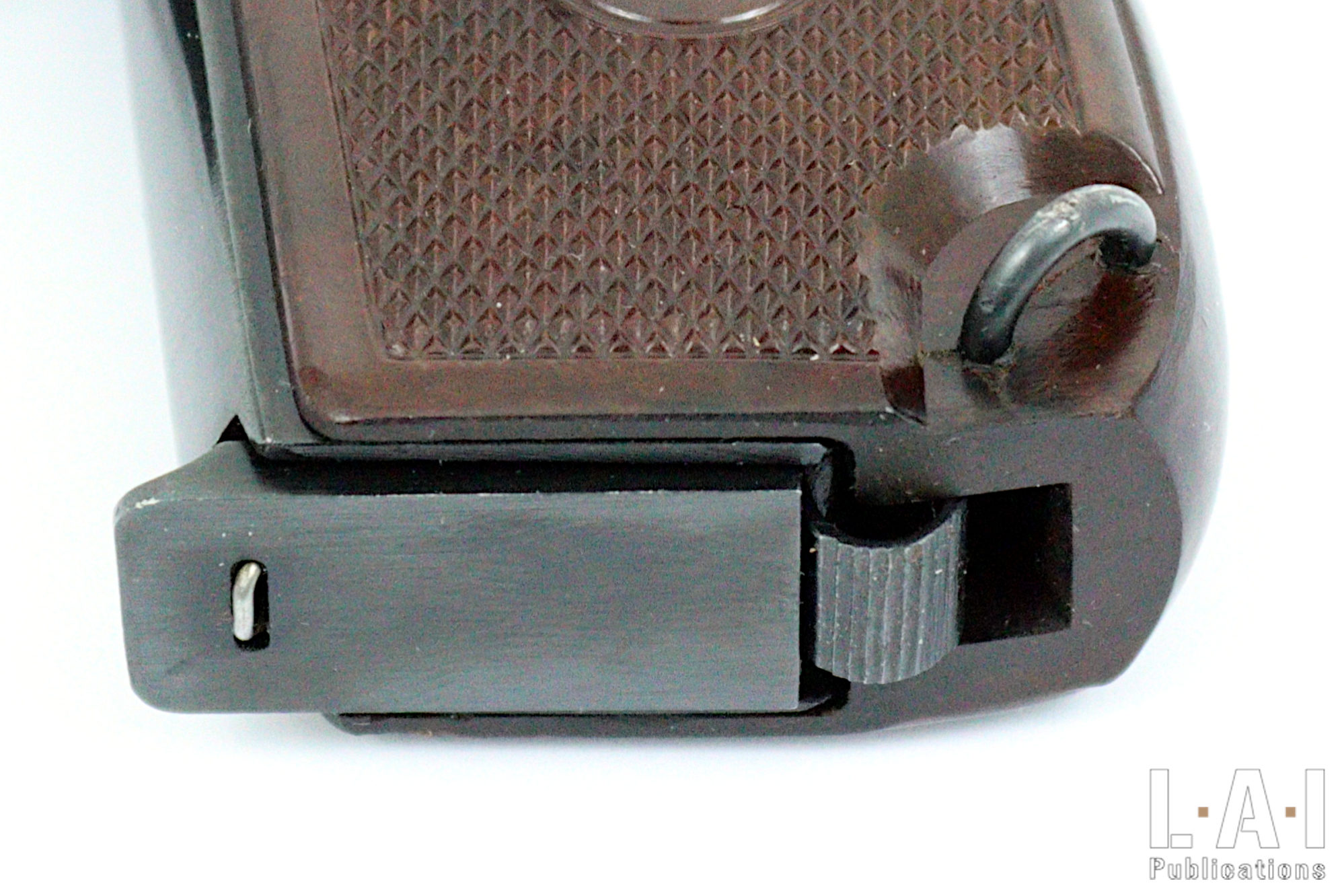

The magazine hook is located at the bottom of the grip… as on a PPK, but also some rare production of the Walther PP (Pic.10). It is interesting to note here an evolution that may seem unnatural compared to the TT 33: the “modern” push button that tend to “eject” the magazine gives way to a device promoting the “extraction” of the magazine … so as not to drop or lose it. No, the Makarov is not a practical shooting weapon designed in a “tacti-cool” spirit! It is an infantry weapon of the Cold War! The weapon is equipped with a slide stop automatically controlled at the end of the magazine which, unlike the German weapon, has an external control on the left side of the weapon (that can be seen on Pic.09).

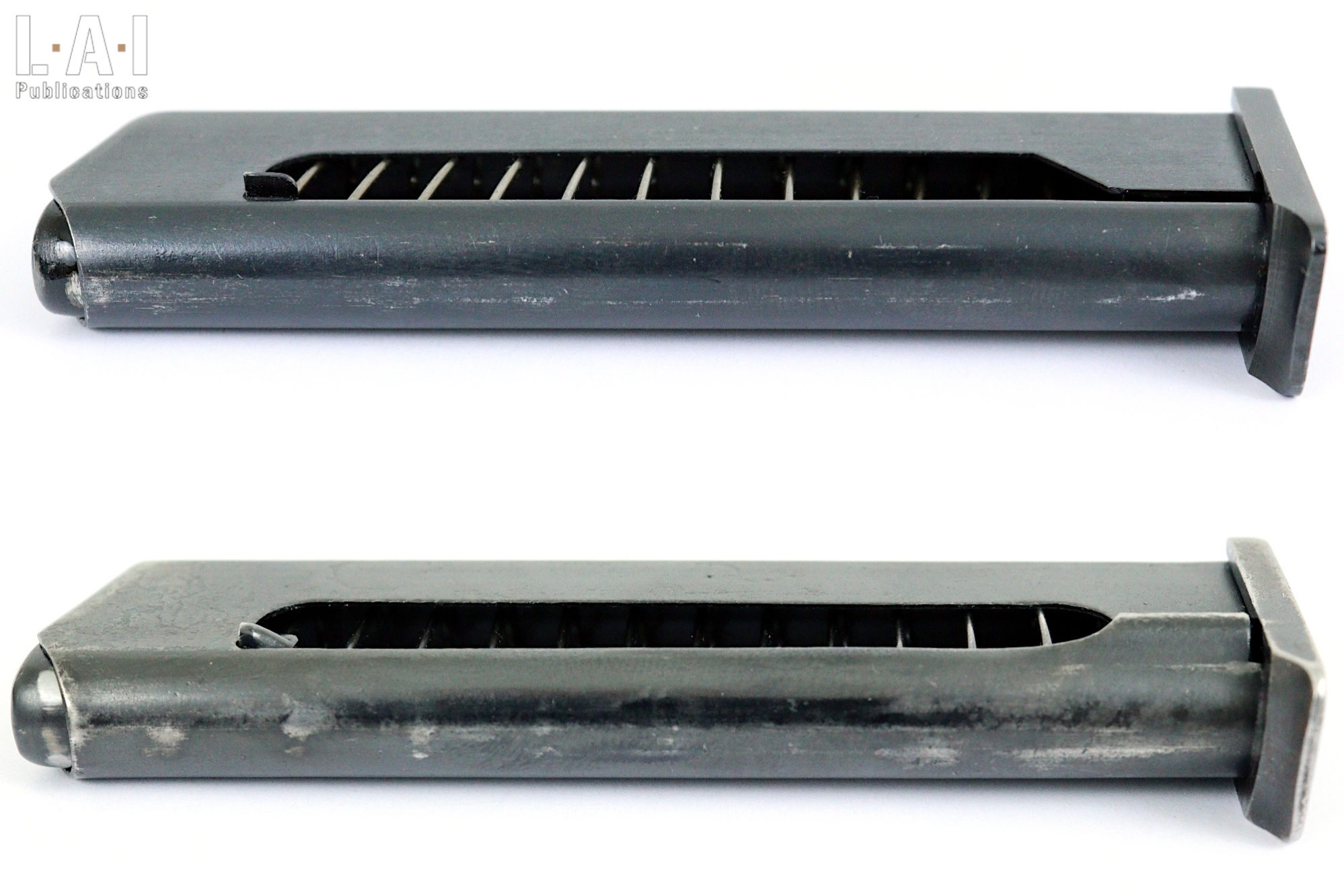

The single-stack magazine has a capacity of 8 rounds. It has wide openings on the sides, which makes it easy to visualize the number of ammunition present and facilitates its loading (Pic.11). These wide openings will also make it possible to limit the ammunition friction inside the magazine’s body and thus to make the weapon more reliable by avoiding slowing down their ascent in the short period of time allowed by the rapid cycle of the weapon.

The weapon is transported in a leather service holster, which contains, in addition to the weapon, an additional magazine and the cleaning rod (Pics.12 and 13). This holster has a leather pull for easier removal of the weapon. Equipped with a wide flap, this holster is well intended to protect the weapon from external elements when carrying the weapon … and not to favor the draw in a …”tacti-cool” spirt! In fact, a service weapon will spend most of its life in the holster without being often drawn! The weapon can be attached to a lanyard that comes to hang on the grip. Unlike the Tokarev, the magazine does not receive a ring for a lanyard.

A very well-designed mechanism

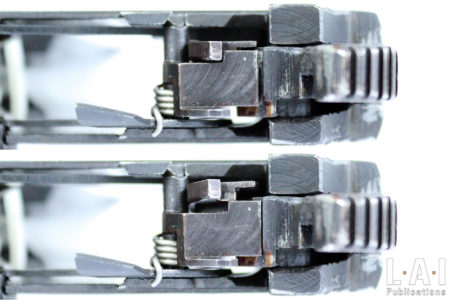

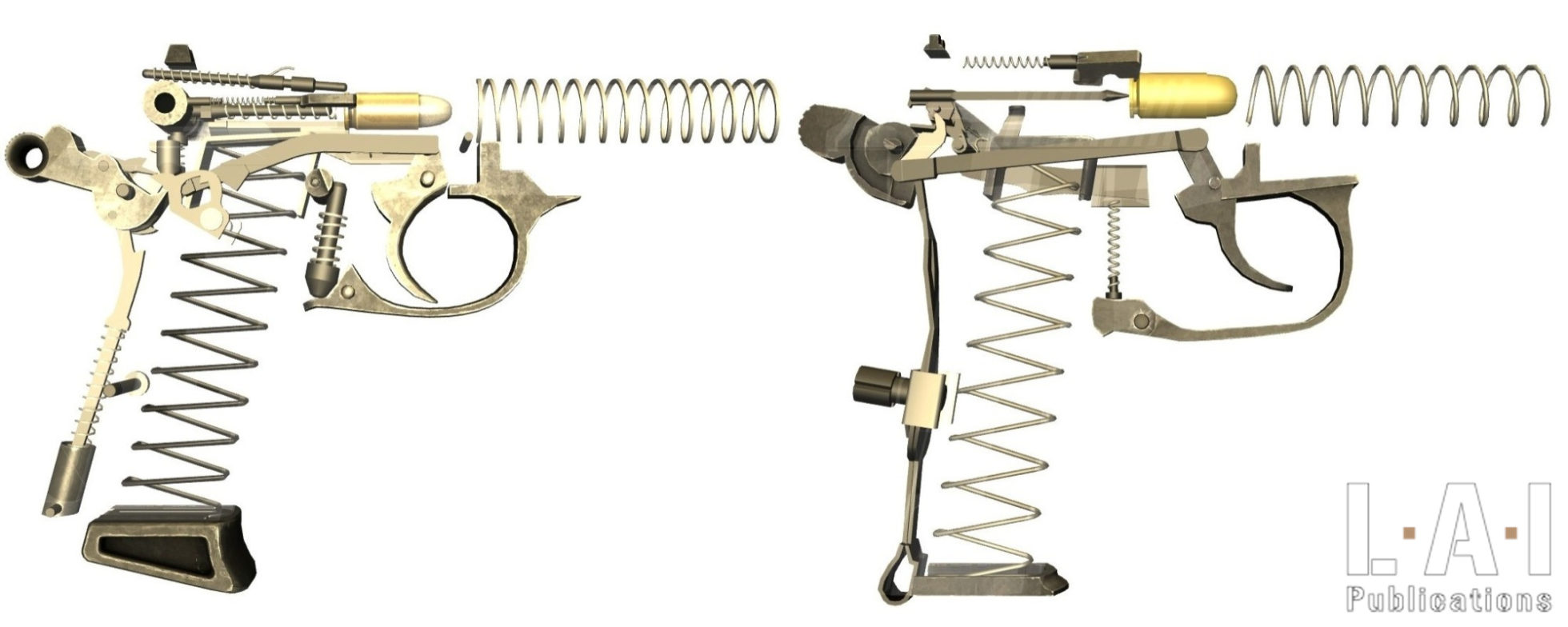

Mechanically, the weapon is finally very different from the Walther PP and actually shares on this level only the straight blowback operating system with the arrangement of the recoil spring around the barrel, the latter being fixed in the frame. Straight blowback is also common to most semi-automatic pistols of .25 ACP, .32 ACP and even .380 ACP caliber. It is by far the simplest to achieve mechanically. Readers wishing to have more details on this operating system (and other technical points mentioned in this article) can consult Chapter 6 of the Small Guide for Firearms available on the same site. As for the use of straight blowback, the arrangement of the recoil spring around a fixed barrel is not specific to the Walther PP: it has been used on handguns since the late nineteenth century! The similarities end here: the Makarov is totally different from the Walther PP in terms of firing system. In total, the Makarov has 31 constituent parts, including 18 moving parts during the implementation and firing phases. For the Walther PP, it is 52 parts in total, including 30 moving parts during the implementation or firing phases (Pic.14).

Let us specify here that we are talking here about “relative” mobility, that is to say parts in motion in relation to each other during the implementation of the weapon. For example, the rear sight (constituent part) which is attached to the slide when firing, is not counted as a moving part because it moves in a way that is attached to the slide during firing. Similarly, when we mention, the “constitutive” parts we count all the parts necessary for the construction of the weapon with the exception of synthetic parts that are molded over other parts: for example, the guiding rails of the Glock are not counted as an additional part vis-à-vis the frame. We consider their presence as a manufacturing operation comparable to a machining phase.

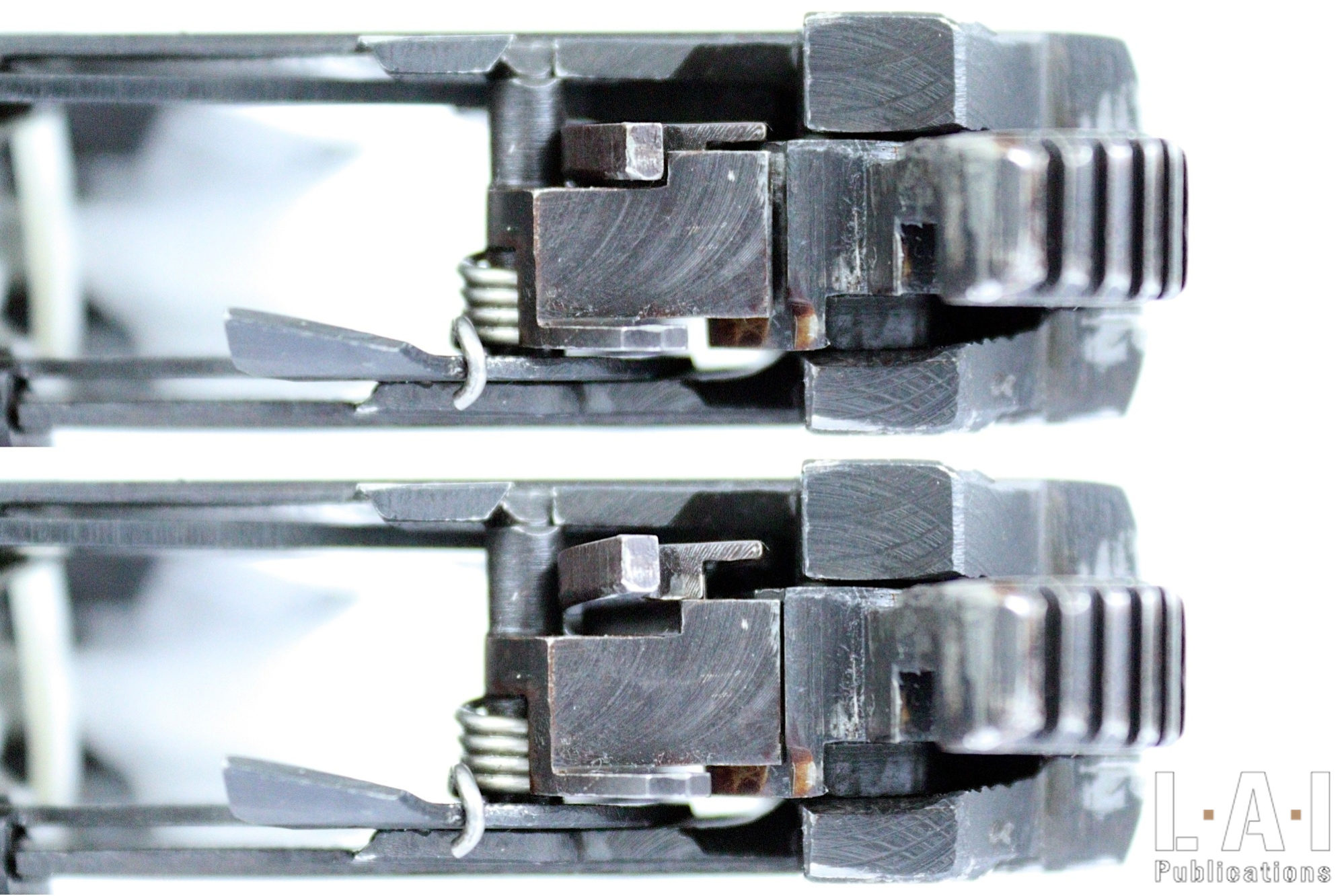

Note that the Walther PP has a feature that the Makarov does not have: a loading indicator (consisting of 2 parts). If the PP has an “automatic hammer block” (consisting of 3 pieces), it lacks a safety notch like the Makarov. These two devices have the same purpose: preventing the forward moment of the hammer until the trigger is activated. And the PP device brings nothing except parts and additional machining: in both cases the device is only controlled by the movement of the sear … and blocks the front movement of the hammer!

Anecdotally, the Makarov is even simpler than a Glock 17: 42 constituent parts for generations 1 and 2, including 23 mobile parts! Also, the Makarov has a much higher number of features: the Glock is a single-action weapon devoid of manual safety whereas the Makarov is single and double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More and also has a decoking lever, which acts as a manual safety as well.

We ask the reader not to fall into the trap set by marketing catchphrases: the name “safe-action” used for the Glock is a trade name and mechanically corresponds to a plain and simple single action where it is necessary, in case of percussion misfire, to re-cock by a slide movement the firing mechanisms. Similarly, the official Glock pistol parts list does not detail all the constituent or moving parts, but only the parts and sub-assemblies sold (sometimes as complete sets) by the manufacturer. There would be much more to say about the “ingenious” marketing of this excellent pistol… For example, the trigger safety is not to be regarded as a “manual safety” (as it is or was advertised, at least in France) since its implementation is not dependent on the shooter’s will but automatic as soon as the shooter removes his finger from the trigger. Is that a problem? No, but there is no “manual safety” on this pistol, the box must not be ticked on the call to tenders.

Be careful, the Glock 17 and Walther PP are excellent weapons, having both influenced their times during their appearances. Mechanically, the Makarov is – from my point of view as a technician – simply superior in terms of design because it is simplified to the extreme. This has industrial and operational implications. On an industrial level, manufacturing is potentially (frequently) faster and cheaper, but on the condition that the parts are not of excessive complexity to manufacture. This last aspect can be questioned in view of certain parts (including the frame, the slide and the hammer): it is however necessary to place the weapon in its context, 1951. Compared to other weapons of the time, with equivalent functionality, the Makarov is undoubtedly cheaper to produce than many weapons… and in particular cheaper than a Walther PP! In addition, we trust the Soviets to have adopted “simple” machining ranges, but probably with many operations. Operationally, in addition to being easy to use (like almost all firearms in reality!), the Makarov is very simple to disassemble and maintain, which is a bonus in the life of the user and in terms of reliability. A well-maintained weapon is a weapon that works when it counts!

Finally, without erecting the adage as a rule, a simple mechanic is generally a reliable mechanism. And here the Makarov conforms well to the adage, it is very reliable. This reliability is therefore due to this simplicity as well as a design of the parts without fragility (to our knowledge!). Note here that the reliability of a weapon is not only due to the weapon itself but also to its ammunition: the Soviets were very rigorous in the manufacture of their ammunition where reliability, once again, was honored.

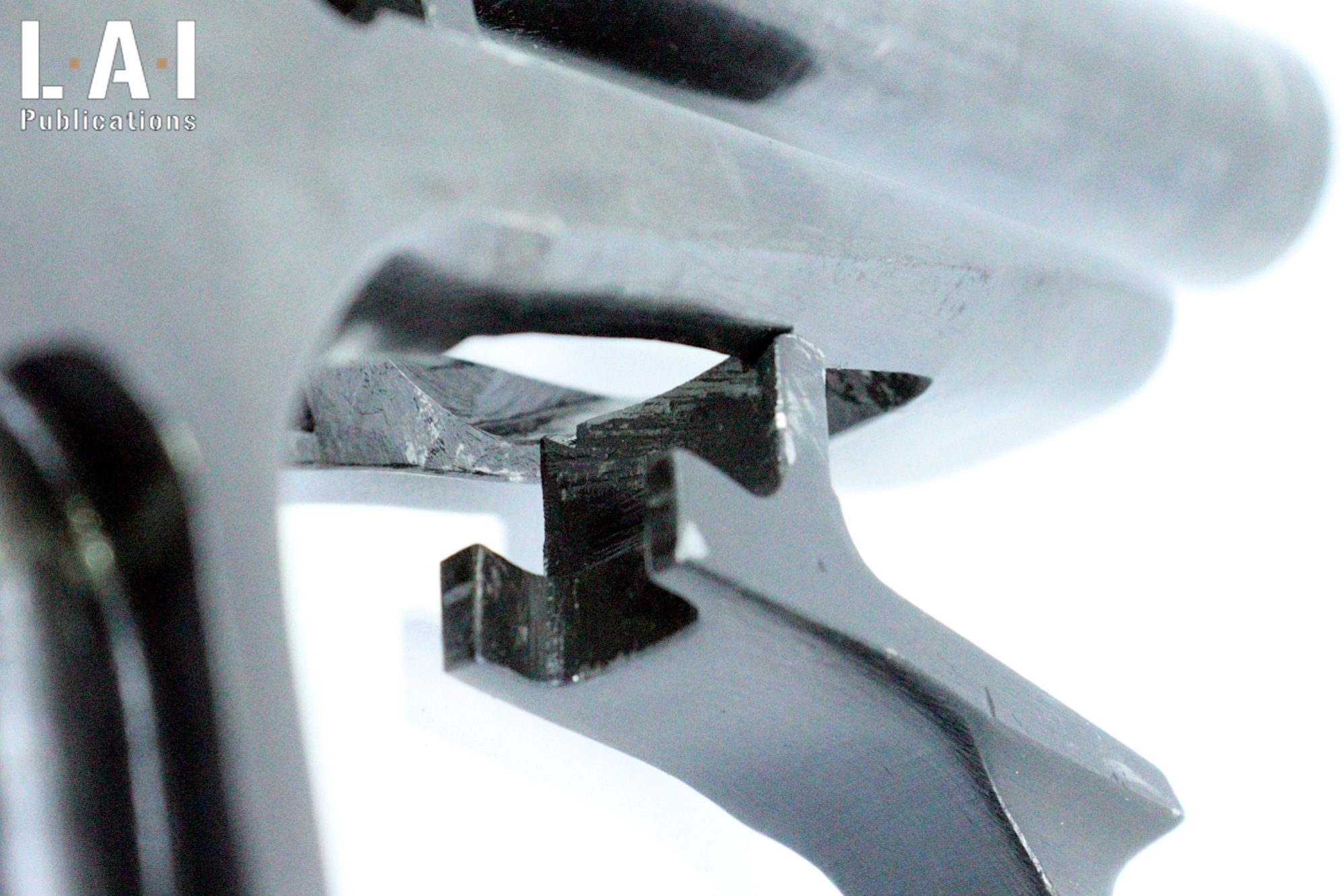

The firing system is therefore particularly well designed and has only a few parts. The disconnector which constitutes the extension of the trigger bar, of a design yet apparently simple (we will return to the notion of apparent simplicity), realizes by its double pivot around the bar and around the hammer the work of single and double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More in a strangely “simple” way (Pic.15):

- In single action: it is brought directly by the hammer to contact the sear during the cocking phase. The sear then holds the hammer by its cocking notch. When firing, the disconnector simply lifts the sear off the arm’s notch.

- In double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More: it engages in the base of the hammer (it acts as a “hammer nose”) to constrain its front part upwards, thus generating the rotation of the hammer in order to cock it and towards the end of the movement it clears the sear by lifting it and then releases the hammer by severing its mechanical connection. In double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More the sear never finds itself in front of the cocking notch, the hammer is released before reaching it. The sear is lifted so as not to bump into the safety notch of the hammer during its shooting.

The disconnection action (action which disconnects all the parts actuated by the trigger from the sear) is carried out by the lateral movement of the disconnector during the recoil of the slide… as on a Glock (Pic.16)! But more than 30 years before! Be careful, I think that this principle of “lateral” disconnection and not “vertical” as on most of semi-automatic pistol can be found on other weapons before the Makarov and I do not think for half a second that Gaston was inspired by the work of Nikolay Fedorovich (so, does it feel good to call the designers by their first names?… Or just pretentious? By the way, subscribe to LAI Publications, there are some people who work hard and deserve a salary!).

If this may seem simple in the description (few parts are involved in the firing kinematic), its design must have been frighteningly complex. N. F. Makarov said that he worked for a long time 7 days a week for nearly 16 to 18 hours a day to perfect (and simplify) his weapon! Most of the time, the more functionalities there are on the simplest mechanics, the more complex they are to design. And the Holy Grail is achieved when these mechanics are reliable and robust! And that’s the case here. We can say that its mechanics are simple, but its design is complex. It is therefore necessary to be wary of an apparent simplicity.

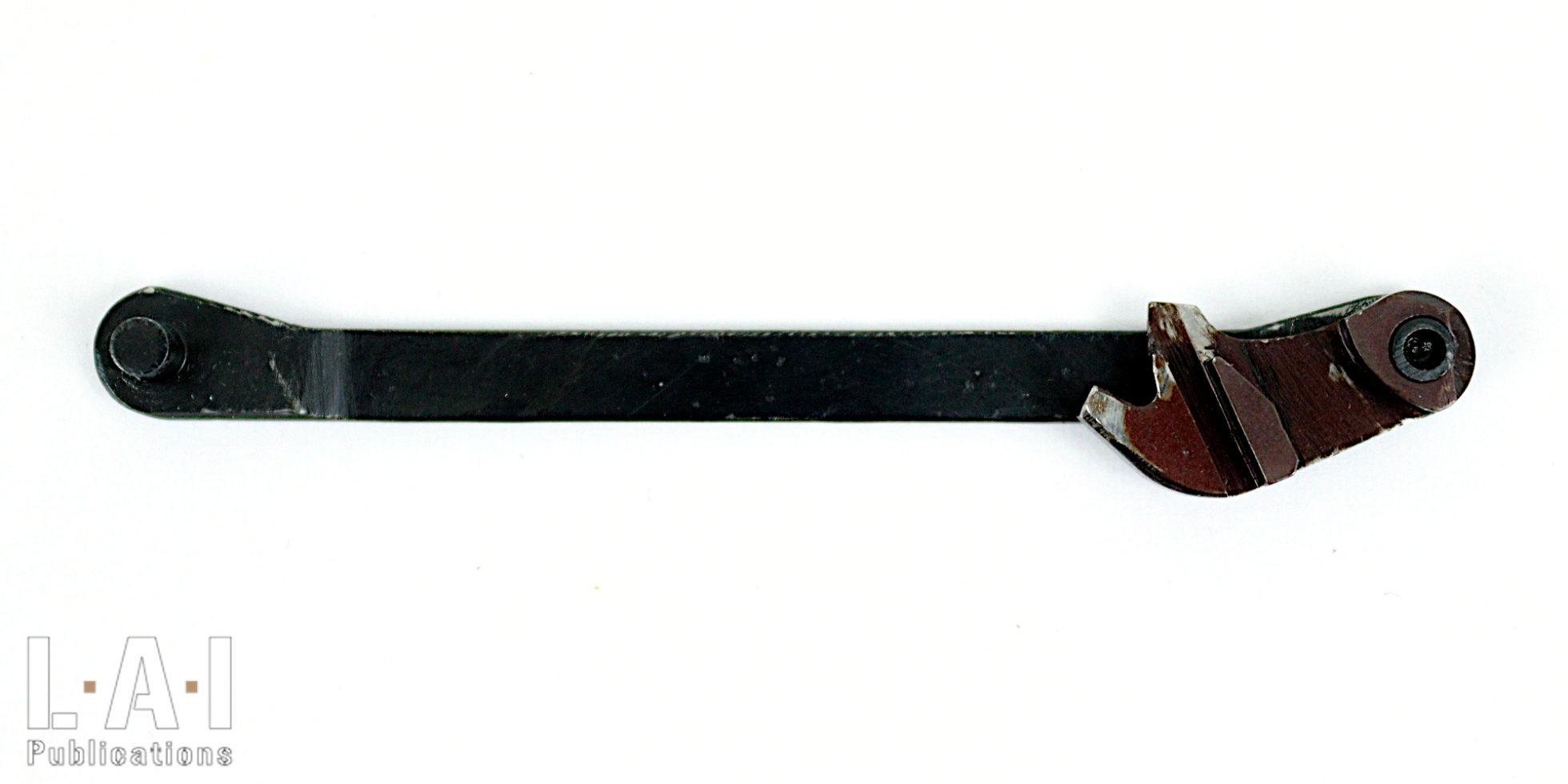

The hammer and the disconnector are powered by the same spring which is a leaf-spring folded on itself, having an extension for each of the parts mentioned above. It officiates as a bonus on its lower part as a magazine hook (the hook and the spring are one and the same piece – Pic.17). As on the Walther PP, the hammer is of a bouncing type. The bouncing is carried out directly by this same spring: its resting position being a “neutral” position where the hammer’s safety notch falls in front of the sear. The percussion therefore takes place on the inertia of the hammer. This spring also achieves, by its tensioning of the disconnector, the return of the trigger via the trigger bar. This leaf-spring, simple and inexpensive on a large scale brings 5 features to the weapon. This desire to multiply the functionalities of each part of the weapon is also found in the sear spring which also performs the function of return spring of the slide stop. The slide stop, made of pressed sheet metal, also acts as the ejector on its upper part. In fact, the multiplication of purpose for the same parts was an obsession among the Soviets which undoubtedly reached its climax with the Makarov. This is obviously the key to the “simplicity” of the weapon.

The slide has few moving parts. The firing pin is assembled by the safety / decocking lever. The percussion is of the “hit and press” type as on the TT 33, but unlike the latter, it is devoid of return spring, the thing having probably been considered superfluous given the hardness of the service primers. As an indication, on the Walther PP, it is of the “hit and throw type”. The extractor is held in position by its pusher, itself put under pressure by the extractor spring. Another big difference with the TT 33: the extractor spring is of considerable size. The cause is simple: the feeding of the Makarov is not controlled as on the TT 33 and, therefore, the ammunition does not slip under the extractor, but the latter must jump over the head of the cartridge. The bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More therefore incorporates this arrangement: it is completely hollow and not smooth on its lower part as on the TT 33 (Pic.18). The purpose of this pattern is probably a better management of the ejection, the spent case being hold in a better way in the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More. The decoking / safety lever acts directly on the sear to release the hammer, and as a bonus comes obstructing access to the firing pin, locking the hammer in the safety position and locking the slide in the closed position.

Manufacturing

The manufacture of these weapons is always neat, but without ostentation… This would be useless for a weapon of war and even economically counterproductive. The exterior surfaces are still mirror polished on all the military copies encountered, the thing being especially useful to limit oxidation: less porosity in the metal, less grips for moisture. The barrels are chrome-plated, a very common arrangement (actually almost systematic from 1951) in Soviet productions of the Cold War. This is necessitated by the widespread use of corrosive (but reliable) primers and steel-jacketed bullets. The chrome plating of the barrels is a significant asset for a service weapon. All other parts are hot-blued. The majority of parts are forged / machined with only four stamped sheet metal parts: the magazine body and its follower, the assembly slider and the slide stop. Seven springs including the ingenious hammer leaf-spring mentioned above. The grip is made of synthetic material of the “Bakelite” type. It is molded over the grip in its synthetic material, the steel buckle for the lanyard and the support / indexing plate for the assembly screw. As mentioned above, the whole, by the intensive use of machining and the complexity of certain parts, questions the cost price! We are clearly not dealing with a weapon designed in the spirit of “mass production” so to speak… while the weapon was produced in very large quantities. This is probably less problematic for a small pistol than for an assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More or a machine gun. Once again, let’s not forget to put the weapon in its context: 1951. In any case, lovers of beautiful mechanics will be satisfied: clearly, from a manufacturing point of view, it is a “beautiful weapon”.

In terms of originality, the slide of the Makarov is machined with a groove on its lower surface to allow the ammunition to rise a little higher before the feeding phase (visible on Pic.18). This arrangement reduces the time required to present the ammunition in front of the slide during reloading, this time being very short on a fast-cycle weapon, such as the Makarov (straight blowback with a very short stroke). While a similar provision is found on some weapons (especially Soviet) with double-stack / double-fed magazine (the bottom of the slide is chamfered on each side for the same purpose), we do not know of such a provision on another single-fed magazine handgun.

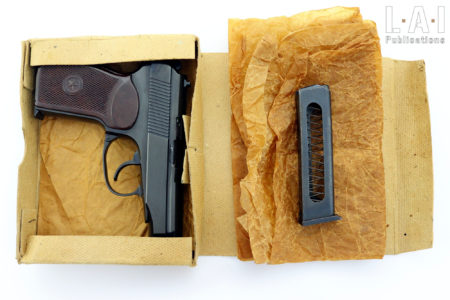

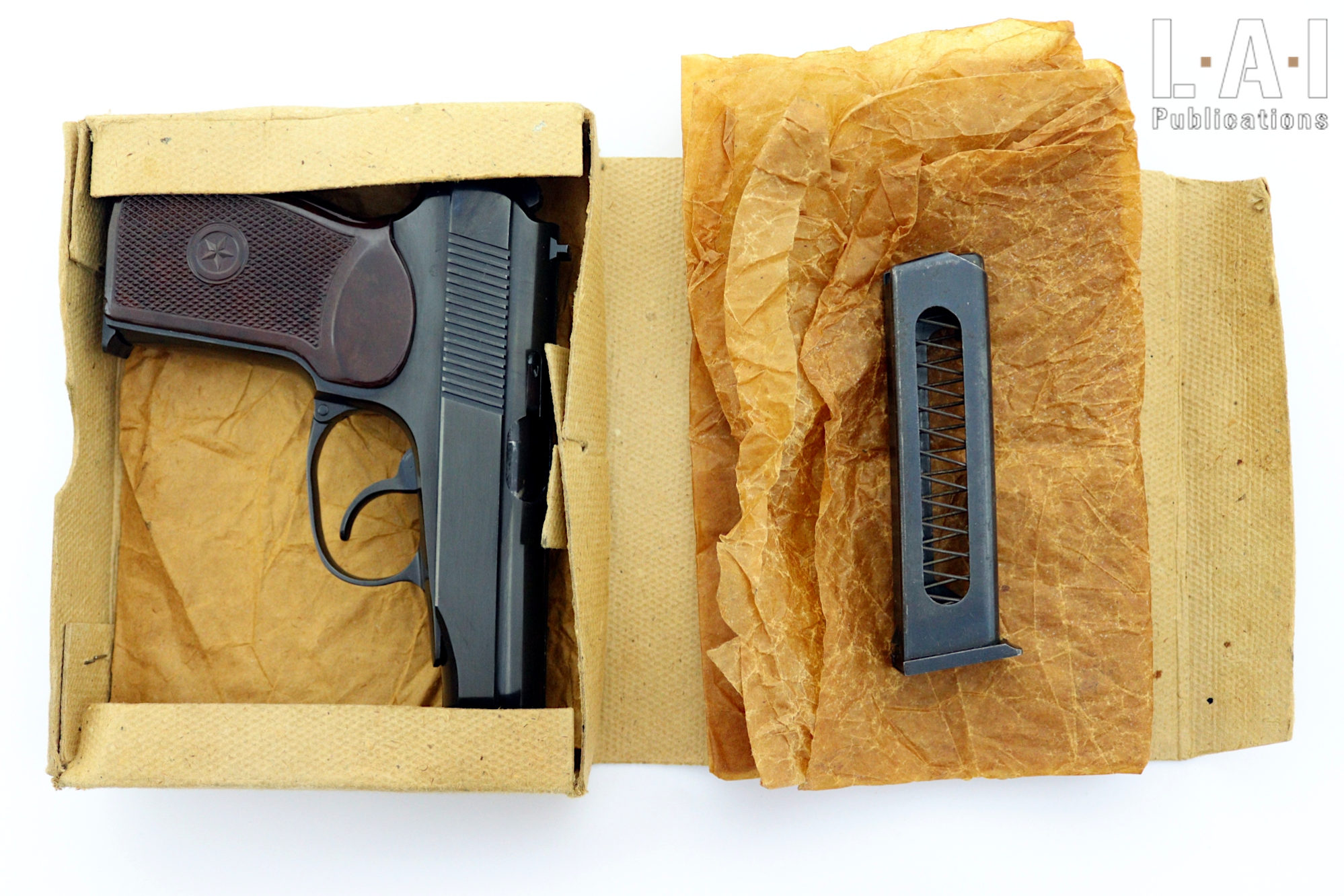

We had the opportunity to examine (and shoot!) in great detail the two military copies illustrating this article:

- A copy made in the USSR in Izhevsk in 1973 (weapons visible on Pics.02 to 05… among others).

- A copy made in Bulgaria by the factory “Arsenal” in Kazanlak in 1980 if the code for years (here 20) for Bulgarian Kalashnikov rifles applies to the Bulgarian Makarov (Pics.19 to 21).

Both weapons are extremely similar in manufacture, perfect for a weapon of war.

The Makarov pistol was manufactured by the USSR/Russia, East Germany, Bulgaria and China. To date, we have not had the opportunity to examine an East German copy, but East German productions, sometimes confusing by a use of synthetic materials unflattering to the eye (but generally of excellent quality) find their place more than often at the top of the basket in terms of quality of manufacture and finish. In this regard, it is good to differentiate between quality of manufacture, which defines the quality with which the mechanical object is made (especially in adjustment and choice of materials) and finish, which defines the aesthetic aspect, but does not necessarily qualify the mechanical quality of the object.

Chinese equipment sometimes suffers from a rather unfair reputation decrying it: in terms of equipment intended for war (and not for the civilian market), the productions we have tested to date are generally very satisfactory in terms of quality and reliability, and very suitable in terms of precision for military use.

The Makarov had some Soviet declination including a modernized post-Soviet version called “PMM” (“Pistolet Makarova Modernizirovannyi ” or “Modernized Makarov Pistol”) using a double-stack / single-fed magazine (for a capacity of 12 rounds) and using the ammunition “9×18 PMM” mentioned above and a silent version called “PB” (“Pistolet Beschumnyil” or “Silent Pistol”). The silencer variant has a barrel perforated several times along its length (Pic.22). The purpose of this arrangement is to allow gases to be vented out of the barrel before the bullet leaves the barrel and thus allow them to be expanded into the chambers of the silencer rather than into the barrel. This allows in the first place an improvement of the attenuation of the noise level by an early “release” of the gases. Also, the bullet naturally loses velocity by this arrangement. This is sometimes the goal sought to avoid the sonic boom of a bullet whose speed is greater than the speed of sound. But it should be noted here that the bullet is natively subsonic in the case of the Makarov, albeit very close to the speed of sound.

Another effect produced by this arrangement is a lowering of the cycle-rate (i.e. slide speed at firing). This counterbalances the effect generally induced by the addition of a silencer: when mounted at the end of the barrel of an automatic reloading weapon, relaxing the gases in confined environments contiguous to the barrel leads to the retention of pressure for a longer time inside the latter. As a result, the bolt (or the bolt carrier group depending on the weapons) undergoes an additional acceleration by this “continuity” of pressure. The way in which the pressure acts depend on the weapons, but frequently it is by direct action on the case and therefore on the breech, as in our case. This is called an “over-cycle”. The over-cycle can be the source of some failures, and this sometimes leads to the adoption of gas regulator with “Normal” / “Silencer ” positions for the sole purpose of making the weapon reliable with a silencer, despite the use of supersonic ammunition. It is not excluded that this provision on the “PB” will be integrated for this reason. In addition, the author Julien Lucot reported to us during a conversation he had noted on many occasions a very slight increase in the speed of the bullet by the addition of a silencer on long guns. We have not conducted a comparative test on this subject (yet!), but the thing does not seem completely incongruous! Thus, it is possible that in the case of the Makarov, the addition of a silencer pushes the bullet to a slightly supersonic speed, with a sonic boom. In all cases, the use of perforated barrels must improve the sound attenuation performance and reliability of the weapon to the detriment of its speed, and therefore its terminal effectiveness. But again, what is the purpose of this material? Certainly not to assault…

Other variations for the civilian market were marketed, some in .380 ACP (Pics.23 and 25) and even the “ИЖ-79-9Т МАКАЫЧ” designed for firing “non-lethal” rubber ammunition of 9 P.A. caliber (the same caliber as blank and gas ammunition). Finally, the 5.45×18 caliber PSM pocket pistol (presented in detail in the article linked here) finds some similarities (actually few of them) with the Makarov.

As with any weapon produced in large quantities by different factories, there are variations in production that are the joy of enlightened collectors! Having had the chance to have on hand a batch of weapons made in Bulgaria, we share with you the pictures of 6 weapons that can illustrate some type of variation encountered (Pics.26 to 38). Let’s be honest: we cannot attest that these weapons are in their original configurations, although it seems that this is the case given the history we know about them.

Disassembly and maintenance

The summary disassembly of the weapon begins almost identically to the Walther PP. After completing the usual security checks:

- If there is a magazine in the weapon, the magazine is removed from the weapon.

- If the slide is at the rear, return the slide to the front.

- The trigger guard is lowered and shifted slightly to one side so that it can rest on one of the edges of the frame. The upper end of the trigger guard has one notch on each side for this purpose (Pic.39). This provision, which makes life easier for the user, is not present on the Walther PP.

- Pull the slide as far as possible towards the rear, then thus positioned, lift the rear part of the slide in order to disengage the slide from the guiding rail present on the frame.

- Thus disengaged from the frame, return the slide to the front of the weapon to remove it from the barrel.

- Remove the recoil spring from the barrel by pulling it while turning it.

This “field” disassembling is sufficient for most routine maintenance operations.

Unlike the Walther, the very advanced (but not complete) disassembly of the weapon is within the user’s reach and only requires the cleaning rod contained in the weapon holster. This rod also serves as a screwdriver and as a pusher / hook (Pic.40). This disassembly is carried out in less than 5 minutes for people used to the exercise, and the reassembly is not much longer … as demonstrated in the video!

We will start with the magazine, the disassembling of which should – in our opinion – be part of the summary disassembling of a weapon:

- Compress the bottom of the magazine spring upwards to dislodge its end from the magazine floorplate.

- When the spring is disengaged from the magazine floorplate, slide it forward.

- Remove the magazine spring and then the follower.

Disassembly of the slide:

- Position the safety lever between “1 and 2 o’clock” in over-running to the “safety” position. Thus positioned, the lever can be extracted by the left side of the slide.

- Once the safety lever is removed, the firing pin can be extracted by gravity. Remember that this one, on all the versions we have encountered to date, does not have a return spring. The firing pin has a specific mounting position, with a notch that must be located on the lower left side, to allow the mounting of the safety lever. Take care to locate the pattern before disassembly.

- Using the end of the cleaning rod, compress the pusher of the extractor in its housing and then tilt the end of the rod between the pusher and the extractor’s foot.

- Thus, separated by the rod, the extractor can be removed by tilting its rear part out of its housing (potentially using the rod).

- Thus tipped, the extractor can exit its housing by the front of the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More. The direction of the extraction is made necessary because the extractor has a return on each side that come to engage in the slide.

- Once the extractor is removed, you can take your pusher and spring out of their housing.

With the exception of the rear sight, the slide is totally disassembled! The most “complex” disassembling operation of the weapon is probably the removal of the extractor.

Disassembly of the frame:

- Make sure the hammer is in the “resting” position.

- Using the blade on the rod (well, no fuss, in absolute terms we prefer a good screwdriver!) unscrew the screw (in fact, the only screw!) on the back of the grip, then remove it.

- Remove the grip from the back of the weapon.

- Slide the hammer spring slider down, then remove it.

- After removing it from the screw housing on the frame, stretch the hammer spring downwards. If the spring is naturally loosened (by elasticity) from the screw housing, it is however necessary to locate the thing for reassembly.

- Using the end of the cleaning rod (or a pick), lift the sear/slide stop return spring and run it over the slide stop to destress it.

- By playing on the elasticity of the slide stop (and in fact, the part that acts as an ejector), rotates the sear upwards by 90°. Thus positioning, it is possible to bring the right side of the sear upwards out from the frame, and thus remove the sear and the slide stop.

- Rotate the hammer 90° forward: thus positioning, it can be extracted out from the frame forward.

- Remove the rear part of the trigger bar from the inside of the frame. It can then be uncoupled from the trigger.

- Position the trigger guard in opened position as for the summary disassembly: the trigger can then be removed from its housing by pushing it forward.

The disassembly is complete! (Pic.41). A few observations:

- The only parts that were not removed are: the rear sight, the trigger guard, its spring and axis, the barrel and its pin!

- Among the disassembled parts: no axis! The pivots used are carried by the parts themselves, with the use twice of “interrupted” pivots (trigger and hammer), which allows, in a precise position, the removal of the part.

- There is still a screw: but it conditions the total access to the firing mechanism. The game is probably worth it! (Note: for a military weapon, the use of the screw, requiring a dedicated tool, subject to deterioration of its footprint and seizure, is generally considered a defect).

The reassembly is done in the reverse, taking the following precautions:

- Position the disconnector correctly when placing the trigger bar: the hinged part must be upwards in the frame.

- Correctly position the sear/slide stop return spring above the ejector.

- The part of the hammer leaf-spring that actuated on the disconnector must be rear of the latter, and not inside its groove.

- Do not tighten the grip excessively: it is advisable to stop on a position of indexation of the screw provided by the spring contained inside the grip.

For maintenance, accessibility is simply excellent.

Shooting with the Makarov

The loading of the magazine is quite easy on its entire capacity: take care not to be injured with the control of the slide stopper which protrudes on the left side of the magazine (Pic.42). This protrusion could also be used as a “button” to assist the loading (provided you do not handle it with your bare hand), but the thing is made totally superfluous because you can simply accompany the descent of the ammunition directly through the wide openings.

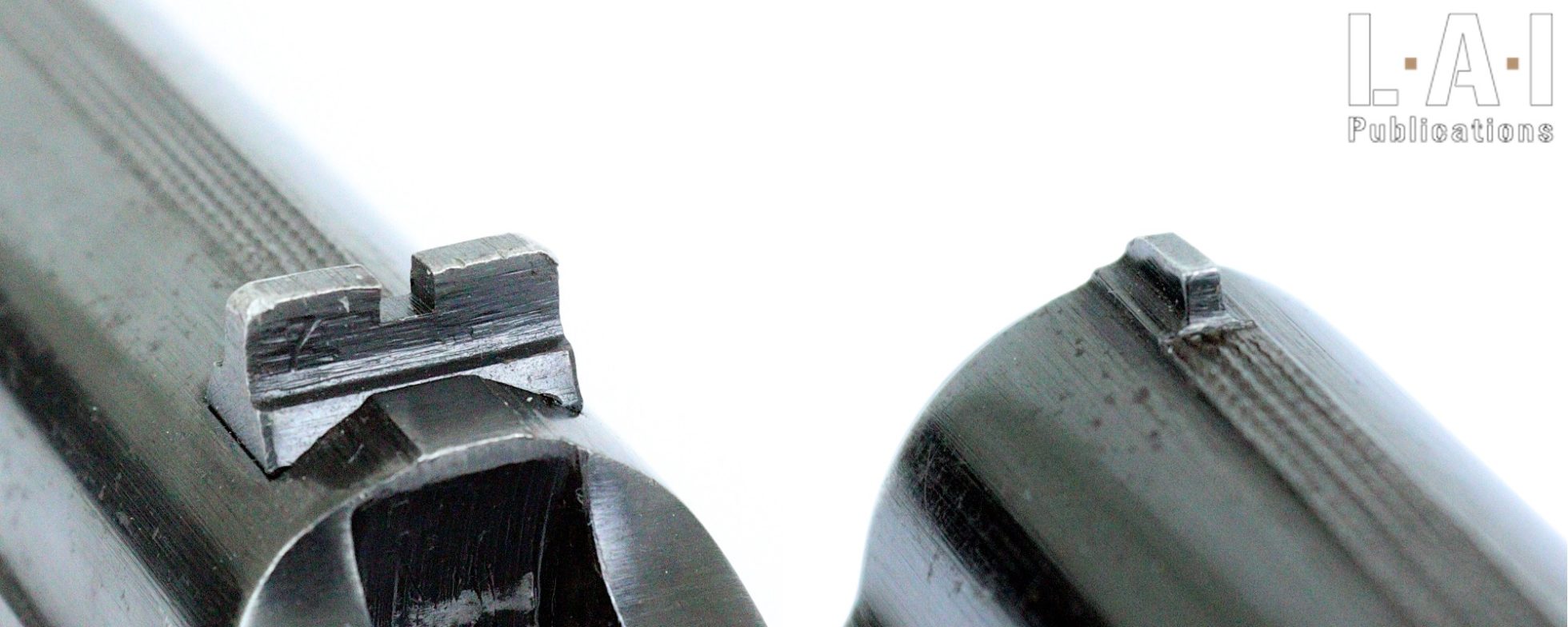

The operations are totally instinctive. The weapon is well in hand for a weapon of its size, the aiming is instinctive and immediate. The sober and effective sights are what can be expected from a weapon of this category (Pics.43 and 44). From our point of view, they are better to an accurate shot than a quick one. Note the existence of several sizes of rear sight to achieve the elevation adjustment. The rear sights number are shown on the rear left side of the copies examined. The direction adjustment is achieved by the lateral movement of the rear sight in its dovetail, probably by a dedicated tool. In the absence of this tool, the thing can be done delicately using a hammer and a brass punch.

The sliding trigger (i.e. without real hard point), of a “Soviet style”, is not unpleasant for a weapon of war and is taken in hand quite easily. It should be noted about this that the “hit probability” improvement among the Soviets is often achieved in such a way as already mentioned in our other works. The reason is simple: the intrinsic accuracy capabilities of weapons of war are often greater than what the average soldier can get out of them. This trigger release improvement, without hard points, increases the number of shots on the target significantly. We must also specify here, that according D.N. Bolotin, the use of a fixed barrel is a significative advantage concerning accuracy regarding the TT 33. Well, it may be true, but some military pistols with a mobile barrel performs excellent accuracy! When firing, the weapon produces a rather low “dry” recoil, quite common to compact 7.65×17 SR caliber straight blowback weapons, but a little deeper in hand than the latter.

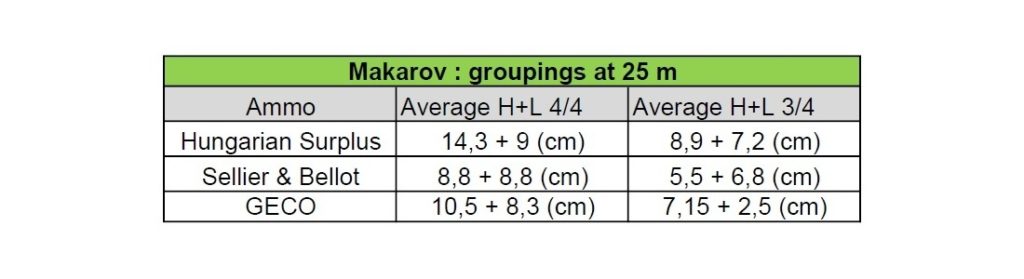

The Soviet manual inform us that the accuracy to be expected from this weapon is 15 cm to 25 m, or an approximate H+L of 11.5 cm + 11.5 cm. Note here that the verification of this accuracy is done according to the Soviet protocol by firing 4 cartridges and keeping the 3 best results. The purpose of this protocol is to eliminate errors related to the shooter or ammunition while remaining pragmatic about the final destination of the weapon: it is a defensive weapon, it is not useful to require too high precision. In this protocol the aiming point must match to the average point of the grouping. This type of protocol is found on other Soviet weapons with a “universal” vocation (AK-47, AKM, AK-74, PK …). The weapons protocol for more specialized troops is a little stricter (SVD-63, APS…). Of course, the weapon is sent for repair (and possibly decommissioned) for accuracy problems when the requirements of these protocols are not met after several tests by several shooters.

The announced accuracy is verified by shooting with our Bulgarian copy:

This one tends to groups high (more than 10 cm above the aiming point at 25 m) which is probably due to a different ammunition during our tests than the one for which the weapon was adjusted. It would have been interesting to have a set of rear sight to adjust the setting… but as with all surplus weapons using this adjustment artifice! Note here that the accuracy tests were carried out on the supports, we do not seek to evaluate the shooter …

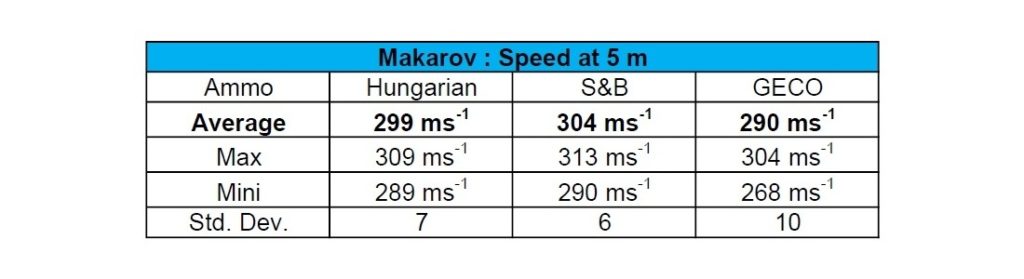

A speed measurement was also carried out at 5 m. We are not at the 315 m/s displayed in the manuals with the ammunition and the conditions of the test, but it is necessary to remain pragmatic once again, the results are good and normal for ammunitions of war.

In conclusion

Given its specifications, the Makarov is undeniably an excellent handgun. To our knowledge, there are no mechanical defects. Today, in a context where the 9×19 is widespread, the main criticism made is the weakness of its caliber. But it is necessary as always to “contextualize” things: the desires of yesterday are not necessarily those of today, nor those of tomorrow. Its caliber, if it “lacks power” in the eyes of some, makes it possible to perfectly fulfill its function as a “defense” weapon, all in a compact weapon, bordering on a pocket pistol. In any case, it is a brilliantly designed weapon and really pleasant and effective to shoot. A remarkable collector’s item: in our opinion, the Makarov remains the Kalashnikov of handguns… and yours truly favorite pistol!

Arnaud Lamothe

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!

Selected bibliography:

- ” Munitions militaires Russes pour armes légères 1868-2008“, by P. Regenstreif, edition Crépin-Leblond.

- « Soviet Small-Arms and Ammunition », par D.N. Bolotin, published by “Finnish Arms Museum Foundation”.

- “Russiche Schusswaffen“, I. Shaydurov, edition Motorbuch-Verlag

- Soviet Service Manual: http://nastavleniya.ru/PM/pms.html